Northrop Frye & Critical Method

Robert D. Denham

Chapter 6: Applied Criticism

Chapter Sections:

Milton

Studies in Literary Periods

The Social Context of Criticism

Separating Frye’s theoretical from his applied criticism suggests a sharper disjunction between them than actually exists in much of his work. Fearful Symmetry, ostensibly a work of practical criticism on Blake’s prophecies, is heavily laden with theoretical speculation. At some places in this book it becomes difficult, especially in retrospect, to determine whether the theory exists for the commentary or vice versa. And since poetry and criticism at the anagogic level are often indistinguishable for Frye, it is not surprising that his commentary on Blake merges into his theory of criticism. Nevertheless, the difference between the theory of criticism and the application of the theory is a distinction Frye himself makes in referring to his own work.

After completing Fearful Symmetry he began a study of The Faerie Queene. But the work was never completed, developing instead, as he tells us in the preface to the Anatomy, into a theory of allegory. This in turn directed his attention toward much larger theoretical issues, the culmination of which, after more than a decade, was the Anatomy itself. “The theoretical and practical aspects of the task I had begun,” he says, “completely separated,” and he speaks of the need for a volume of “practical criticism, a sort of morphology of symbolism,” to complement the “pure critical theory” of the Anatomy (AC, vii). Frye’s critical theory is seldom “pure,” insofar as his continual reference to specific works suggests, at least, the general shape a more detailed commentary would take. Conversely, his commentary on individual writers and works is, at the same time, theoretical, as it must be for any critic, since all critical methods include theoretical assumptions, if but implicit ones. Nonetheless, we can classify most of Frye’s criticism into two broad categories, depending upon whether his aim is primarily to develop a method for doing practical criticism or whether he is actually engaged in specific interpretation, explication, or commentary on individual writers.1

Frye has produced a substantial body of this latter kind of criticism. In Fables of Identity he treats a number of specific works {158} and writers, even though this book is hardly the sequel, he says, that he had in mind when he wrote the Anatomy (FI, 1). It contains discussions of The Faerie Queene, Shakespeare’s sonnets, Lycidas, Blake, Byron, Emily Dickinson, Yeats, Wallace Stevens, and Finnegans Wake. Frye has written two books on Shakespeare, one on Milton, still another on Eliot, and a major book on the Bible is in progress. A large body of practical criticism is included in his three other volumes of selected essays: The Stubborn Structure, Spiritus Mundi, and The Bush Garden, a collection of his essays and reviews on Canadian writers.2 His book on English Romanticism contains long essays on Beddoes’s Death’s Jest-Book, Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound, and Keats’s Endymion. The list of such studies is lengthy.3

The practical criticism is by no means single in aim or approach. Frye can analyze poetic texture after the manner of the New Critics. He can use his discussion of individual works as a means for defining literary periods, the procedure followed in his book on English Romanticism and his essay on the “Age of Sensibility” (FI, 130–37). He can engage in interpretative commentary on individual passages. As we might expect from our study of the Anatomy, however, none of these practices is typical of Frye’s approach. More often than not he is concerned not with detailed commentary on individual poems but with the whole of a writer’s work.4

The great merit of explicatory criticism was that it accepted poetic language and form as the basis for poetic meaning. On [this] basis it built up a resistance to all “background” criticism that explained the literary in terms of the non-literary. At the same time, it deprived itself of the great strength of documentary criticism: the sense of context. It simply explicated one work after another, paying little attention to genre or to any larger structural principles connecting the different works explicated. (CP, 20)

Frye’s own sense of context, however, is not that of documentary or historical criticism. The following passage, in which Frye recounts his reaction to deterministic, historical, and exclusively rhetorical approaches, spells out clearly the kinds of contexts he has in mind:

It seemed to me obvious that, after accepting the poetic form of a poem as its primary basis of meaning, the next step was to look for its context within literature itself. And of course the most obvious literary context for a poem is the entire output of its author. . . . Every poet has his own distinctive structure of imagery, which usually emerges even in his earliest work, and which {159} does not and cannot essentially change. This larger context of the poem within its author’s entire “mental landscape” is assumed in all the best explication—Spitzer’s, for example. I became aware of its importance myself, when working on Blake, as soon as I realized that Blake’s special symbolic names and the like did form a genuine structure of poetic imagery. . . . The structure of imagery, however, as I continued to study it, began to show an increasing number of similarities to the structures of other poets. . . . I was led to three conclusions in particular. First, there is no private symbolism. . . . Second, as just said, every poet has his own structure of imagery, every detail of which has its analogue in that of all other poets. Third, when we follow out this pattern of analogous structures, we find that it leads, not to similarity, but to identity. . . . I was still not satisfied: I wanted a historical approach to literature, but an approach that would be or include a genuine history of literature, and not simply the assimilating of literature to some other kind of history. It was at this point that the immense importance of certain structural elements in the literary tradition, such as conventions, genres, and the recurring use of certain images or image-clusters, which I came to call archetypes, forced itself on me. (CP, 21–23)

The convictions outlined in this passage determine the way Frye characteristically approaches literature. As a practical critic he typically seeks to place individual works within the context of a writer’s entire canon and to relate them in turn by way of generic and archetypal principles to the literary tradition, what he calls the total order of words. Frye’s practical criticism therefore is contextual, using the word in both the senses just mentioned. His conception of the total order of words is not unlike Eliot’s belief (in “Tradition and the Individual Talent”) that the literature from the time of Homer has a simultaneous existence and composes a simultaneous order. More than once Frye echoes this belief, arguing that the literary tradition operates creatively on the poet as a craftsman (AC, 17; CP, 23). But he goes beyond Eliot in attempting to identify the conventions that permit the poet to create new works of literature out of earlier ones.5

When we consider the writers to whom Frye has devoted the most attention, another characteristic of his practical criticism becomes apparent: his Romantic sensibilities and his predisposition to the forms of romance. He refers to Coleridge’s division of literary critics into either Iliad or Odyssey types, meaning that one’s “interest in literature lends to center cither in the area of tragedy, realism, and irony, or in the area of comedy and romance.” “I have always,” he says, “been {160} temperamentally an Odyssean critic” (NP, 1, 2). In another context he remarks, “Romance is the structural core of all fiction” (SeS, 15). This helps to explain the prominence which Blake, Spenser, Milton, and later Shakespeare, Shelley, Keats, William Morris, and Wallace Stevens assume in Frye’s view.

Moreover, these are writers whom he locates in the “central tradition of mythopoeic poetry” (FI, 1). This is the tradition, Frye says, whose primary tendencies are Romantic, revolutionary, and Protestant. There is a note of ironic parody here, directed against the Classical, royalist, and Anglo-Catholic pronouncements of Eliot. But Frye means to be taken quite seriously. Despite his disclaimers about preferring one of these traditions to the other (FI, 149), there is no question about the locus of his deepest sympathies. He is convinced that the prejudices of modernism are still with us, and thus much of his practical criticism is part of a larger effort to right the balance. He sees the Catholic, Tory, and Classical emphases of modernism as a “consciously intellectual reaction” to the Romantic tradition (FI, 149). The “most articulate supporters” of the reaction, he says,

were cultural evangelists who came from places like Missouri and Idaho, and who had a clear sense of the shape of the true English tradition, from its beginnings in Provence and mediaeval Italy to its later developments in France. Mr. Eliot’s version of this tradition was finally announced as Classical, royalist, and Anglo-Catholic, implying that whatever was Protestant, radical, and Romantic would have to go into the intellectual doghouse. Many others who did not have the specific motivations of Mr. Eliot or of Mr. Pound joined in the chorus of denigration of Miltonic, Romantic, liberal, and allied values. . . . Although the fashion itself is on its way out, the prejudices set up by it still remain. (FI, 149)

This passage comes from an essay on Blake and is a part of Frye’s argument that Blake must be seen in the context of his own tradition. And the “fashionable judgments” about this tradition, he says, have consisted mainly of “pseudo-critical hokum” (FI, 149). Frye has written a great many pages about the Romantic tradition in an effort to rescue it from these “fashionable judgments.” He sees Romanticism as “one of the most decisive changes in the history of culture, so decisive as to make everything written since post-Romantic, including, of course, everything that is regarded by its producers as anti-Romantic” (FI, 3). Although his polemic against the prejudices of modernism is couched in the language of value, belief, and intellectual commitment, his several essays toward a definition of Romanticism approach the issue from a different {161} perspective.6 “What I see first of all in Romanticism,” he says, “is the effect of a profound change, not primarily in belief, but in the spatial projection of reality. This in turn leads to a different localizing of the various levels of that reality. Such a change in the localizing of images is bound to be accompanied by, or even cause, changes in belief or attitude. . . . But the change itself is not in belief or attitude, and may be found in, or at least affecting, poets of a great variety of beliefs” (SS, 203). In other words, Romanticism as a literary phenomenon represents a profound change in poetic imagery and an equally profound modification of the traditional idea of four levels of reality, that background or “topocosm” against which images are portrayed. The point I want to emphasize is that the significance Frye attaches to Romanticism as a revolutionary cultural movement has important consequences for his practical criticism. This emphasis, along with his taste for comedy and romance (most fully developed in The Secular Scripture), and his liberal and Protestant sympathies, goes a long way toward explaining the selection of those writers he has discussed in some detail. One of these is Milton.

Milton

Frye’s book on Milton, The Return of Eden, is a typical example of his work and one that specifically applies many of the principles set forth in Anatomy of Criticism. In addition, Milton is central in the development of Frye’s own thought. The realization that Blake and Milton were connected by their use of the Bible is what pulled Frye toward the study of mythological frameworks in the first place (SM, 17). The Return of Eden is not a work of historical scholarship: Frye disclaims having “knowledge of Milton sufficiently detailed to add to the body of Milton scholarship or sufficiently profound to alter its general shape” (RE, 3). And although subtitled “Five Essays on Milton’s Epics,” it is more than a work on Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained; Frye continually moves beyond these poems, engaging finally a large part of Milton’s thought and art.7

Each of the five essays is organized around a central theme: the encyclopaedic nature of epic forms and the hierarchical structure of Renaissance imagery; Milton’s cosmology and its relation to his doctrine of good and evil; the Miltonic view of reason, will, and appetite as these manifest themselves on each of the levels of reality outlined in the first and second chapters; the themes of liberty and Milton’s revolutionary art; and the typology or structure of Paradise Regained and its relation to Paradise Lost. Such a summary of topics says very little about Frye’s method of study or the unity of his argument. His method {162} depends on a number of the assumptions and principles outlined in the Anatomy. How does his argument illustrate the relation between theory and practice?

The central theme of Milton’s epics, according to Frye, is the return of Eden. Eden represents the condition of freedom to which man aspires. It is to be found only within man, because for Milton the proper locus of God’s presence is not in nature or history. Frye assumes, then, that Eden is the central archetype of Milton’s epics. Their central myth is the loss and recovery of this “paradise within.”

To illustrate this central theme, Frye calls upon a number of broad parallels, recurring analogues, and symmetrical patterns. In the Anatomy he maintains time and again that literature can be viewed in two ways, temporally and spatially. These two concepts are defined variously, according to the context of his discussion. Most often they are related to mythos and dianoia, to the narrative movement in time and the static structure of imagery. Both categories are fundamental to his study of Milton. The spatial aspect of Milton’s work is especially emphasized in Frye’s first three chapters, where he uses the Renaissance framework of four levels of existence to organize the characteristic themes, concepts, and imagery of Paradise Lost. This part of his discussion is a specific application of what I have previously called “the dianoia of archetypal imagery.”

Frye begins his study, however, with the question of genre. For Milton the epic ideal was “a poem that derived its structure from the epic tradition of Homer and Virgil and still had the quality of universal knowledge which belonged to the encyclopaedic poem and included the extra dimension of reality that was afforded by Christianity” (RE, 7). Paradise Lost, Frye argues, incorporates each of these Renaissance assumptions. In the first place, since Milton’s is a Christian epic, its shape derives “ultimately from the shape of the Bible” (RE, 9), which, as Frye has claimed in the Anatomy, is the prototypical or definitive encyclopaedic form. Paradise Lost, he says, follows the Biblical pattern from the Creation to the Last Judgment, surveying the complete history of man in between. A condensed version of this encyclopaedic pattern is to be found in the speech of Michael (RE, 9–10).

Second, Milton is influenced by those prose forms which the Renaissance critics accepted as major genres. The most familiar of these were the Platonic dialogue, the description of the ideal commonwealth, and the educational treatise or cyropaedia. We have a versified form of these genres, according to Frye, in the speech of Raphael: “the colloquy of Raphael and Adam is a Socratic dialogue without irony, a symposium with unfermented wine, a description of an ideal commonwealth ending with the expulsion of undesirables, and (for Adam is the king {163} of men) a cyropaedia, or manual of royal discipline. It is essentially the education of Adam, and it covers a vast amount of knowledge, both natural and revealed” (RE, 12). Third, Milton draws upon the tradition of Homer and Virgil. There are three important ways in which Paradise Lost is influenced by the Odyssey and the Aeneid: all three epics are organized in twelve books (or a multiple of twelve); their narratives are neatly divisible into two parts; and, as Frye has argued in the Anatomy, their total actions follow a cyclical design (RE, 12–14).

This formal symmetry is what fascinates Frye, and to carry the design “much further,” he proposes that we “visualize the dial of a clock, with the presence of God where the figure 12 is” (RE, 18). He then distributes the “main events” of Paradise Lost around the face of the clock as follows:

- First epiphany of Christ: generation of Son from Father.

- Second epiphany of Christ: triumph after three-day conflict.

- Establishment of the natural order in the creation.

- Establishment of the human order: creation of Adam and Eve.

- Epiphany of Satan, generating Sin and Death.

- Fall of the human order.

- Fall of the natural order: triumph of Sin and Death.

- Re-establishment of the natural order at the end of the flood.

- Re-establishment of the human order with the giving of the law.

- Third epiphany of Christ: the Word as gospel.

- Fourth epiphany of Christ: the apocalypse or Last Judgment. (RE, 20-21)

The first four of the phases “represent the four main events in the speech of Raphael” (RE, 18); and the last four, the events in the speech of Michael (RE, 19).

Frye’s argument for this grand design depends more on assertion than on demonstration: he gives no reason from the poem itself which would lead us to believe Milton intended to use this kind of pattern. The symmetrical scheme depends rather upon his prior assumptions about the epic as a genre and about Milton’s relation to the epic tradition. The form of Frye’s argument is this: the total action of an epic is by definition cyclical (a major premise taken over from the Anatomy); Milton was influenced by the formal symmetry and duodecimal organization of the classical epic; therefore we can expect the structural pattern of Paradise Lost to follow a symmetrical, twelve-part cycle. Some of the problems attendant on this kind of argument will be considered later.

{164} As a pattern of themes, the diagram of Milton’s formal symmetry represents what Frye in the Anatomy calls poetic dianoia; as a cyclical movement, it represents poetic mythos. In the Anatomy Frye classifies Paradise Lost as a thematic epic in the high-mimetic mode (AC, 58), which means that in reading it our interest is directed primarily toward its idea or poetic thought, rather than toward its internal fiction. Because one of Milton’s chief themes is heroic action, we might expect Frye’s analysis of heroism to rely upon the principles of the First Essay, where fictions are classified according to the hero’s power of action. But Frye does not follow this course, the reason being that Paradise Lost is primarily a thematic (rather than a fictional) work. He turns rather to his familiar hierarchical paradigm: the idea of four orders of existence (divine, angelic, human, and demonic). These orders underlie his discussion of Milton’s view of heroic action.8

His argument, briefly, is this. First, Milton conceives of God as the source of all real action. “It is only the divine,” Frye says, “that can really act, by Milton’s own definition of an act” (RE, 23); and this, according to what Milton says in The Christian Doctrine, is the power of expression of a free and conscious being (RE, 21). More specifically, the action of Paradise Lost at the divine level is revealed as “an act of creation, which becomes an act of re-creation or redemption after the fall of man” (RE, 23). Second, at the angelic order, the norm for heroic action is to be found in the moral models provided by Gabriel (responsibility), Raphael (instruction), Michael (command), Uriel (vigilance), and especially by Abdiel (obedience). The power of action possessed by the angels, however, derives from God and is contained by Christ (RE, 24–25); thus the difference between the divine and angelic orders is really one of degree. Third, in the human order of existence—the order of Adam—action is defined negatively as the “surrendering of the power to act” (RE, 21). Adam’s fall, symbolized by his eating the forbidden fruit, is an act by which he loses his freedom. Thus, Frye says, for Milton, “a typically fallen human act is something where the word ‘act’ has to be in quotation marks. It is a pseudo-act, the pseudo-act of disobedience, and it is really a refusal to act at all” (RE, 22). Finally, at the demonic level, action involves rivalry with God. Hence demonic action, as manifested by Satan and Nimrod, is a parody of divine action because it aims at destructiveness rather than creation.

Frye sees these four orders of existence as the background against which the total action of Paradise Lost is played out. It involves a conflict between divine and demonic heroism, between fallen man’s inability to act and the angelic models for the truly heroic act. The resolution to this conflict will come about when true heroism is seen as the free, creative, and redemptive act. Milton’s poem therefore contravenes the {165} traditional concept of heroism. “The fact that conventional heroism, as we have it in Classical epic and medieval and Renaissance romance, is associated with the demonic in Milton means, of course, that Paradise Lost is a profoundly anti-romantic and anti-heroic poem” (RE, 28). Milton will not identify freedom with “consciousness centered in the ego” or with “the works of God in our present world,” both of which characterize the traditional epic hero. Human freedom, for Milton, is above nature. Frye puts it this way in the concluding words to his first chapter:

[For Milton] the free intelligence must detach itself from this world and unite itself to the totality of freedom and intelligence which is God in man, shift its centre of gravity from the self to the presence of God in the self. Then it will find the identity with nature it appeared to reject: it will participate in the Creator’s view of a world he made and found good. This is the relation of Adam and Eve to Eden before their fall. From Milton’s point of view, the polytheistic imagination can never free itself from the labyrinths of fantasy and irony, with their fitful glimpses of inseparable good and evil. What Milton means by revelation is a consolidated, coherent, encyclopaedic view of human life which defines, among other things, the function of poetry. Every act of the free intelligence, including the poetic intelligence, is an attempt to return to Eden, a world in the human form of a garden, where we may wander as we please but cannot lose our way. (RE, 31)

This passage, with its Blakean overtones, is Frye’s initial formulation of Milton’s central theme. In order to understand Milton’s treatment of this theme, Frye believes it necessary for us to know something about the genre in which it is found; thus his discussion of the epic and the encyclopaedic conventions. But it is also necessary for us to know how Milton adapts and goes beyond the classical conventions; thus Frye’s discussion of Milton’s particular conception of heroic action. In both cases, Frye draws upon principles set forth in Anatomy of Criticism.

In the remainder of the book the cosmological or hierarchical model is especially important. It guides Frye’s discussion in the second and third chapters. In the Anatomy he observes that “in studying poems of immense scope, such as the Commedia or Paradise Lost, we find that we have to learn a good deal of cosmology” (AC, 160). He suggests that the form of cosmology is quite close to that of poetry and that “symmetrical cosmology may be a branch of myth. If so, then it would be, like myth, a structural principle of poetry” (AC, 161). In the Return of Eden, he finds that he cannot discuss crucial events in Paradise Lost, like {166} the fall, without reference to its cosmology. Milton’s is a four-storied cosmos, the orders of which Frye represents as follows:

- The order of grace or heaven (the place of God’s presence).

- The “proper” human order (symbolized by Eden and the Golden Age).

- The physical order.

- The order of sin, death, corruption.

There is an obvious similarity between this hierarchy and the four orders Frye employs in his first chapter to discuss heroic action (divine, angelic, human, and demonic). The difference is that the possibilities for human existence are not restricted to the third (human) level of his initial paradigm: man can exist on any of the last three levels. In Milton’s view, man is born into the physical order. He can either rise above this station into his proper humanity, living the way God intended him to live, or he can sink below into the world of sin and corruption. In other words, man does not really belong in the world of physical nature; true nature or proper humanity for him is found at the angelic level. Milton makes certain modifications, however, in this traditional view of the cosmos:

In the first place, heaven itself is a creation of God like the angels, and consequently heaven is a part of the order of nature. The angels in Milton are quite familiar with the conception of nature: Abdiel says to Satan, for example: “God and Nature bid the same.” Then again, in Paradise Lost, the whole of the order of nature falls with the fall of Adam, and with the fall of nature, as described in Book Ten, the stars turn into beings of noxious efficacy, meeting “in Synod unbenign.” As far as man is concerned (I italicize this because it is a hinge of Milton’s argument), the entire order of nature is now a fallen order. The washing away of the Garden of Eden in the flood symbolizes the fact that the two levels of nature cannot both exist in space, but must succeed one another in time, and that the upper level of human nature can be lived in only as an inner state of mind, not as an outward environment. (RE, 41)

This is typical of the way Frye uses the cosmological framework to explain Milton. In other words, Milton selects what he wants from the Ptolemaic tradition and from the Great Chain of Being and adapts it to fit his own theological concerns. And we cannot understand Milton, Frye would argue, unless we are aware of this larger cosmological framework, for the activity of God, regularly symbolized in Milton by music and harmony, takes place within this framework. {167} “The Creator,” says Frye, “moves downward to his creation in a power symbolized by music and poetry and called in the Bible the Word, releasing energy by creating form. The creature moves upward toward its Creator by obeying the inner law of its own being, its telos or chief end which is always and at all levels the glorifying of God” (RE, 50).

There is a corresponding demonic dialectic which takes a number of forms, and which Frye refers to as the demonic parody of the divine. We see the upward demonic movement, for example, in “the destructive explosion from below associated in Milton’s mind from earliest days with the Gunpowder Plot” (RE, 50-51). The same movement is repeated in the Limbo of Vanities, “the explosion of deluded souls trying to take heaven by storm” (RE, 51). The downward movement is expressed by the descent into hell by the devils. This is just one of the many details of the “vast symmetrical pattern” of the demonic parody of good. A number of details, Frye says, are obvious: the council of hell versus the council of heaven; Christ’s journey into chaos to create the world versus Satan’s journey to destroy it; the City of Pandemonium versus the City of God (RE, 51). But some details, according to Frye, are not so obvious to the modern reader, though they would be to Milton’s ideal reader—to one, that is, who read the Bible typologically. Frye’s examples are drawn from Milton’s imagery, like his juxtaposition of the tower of Babel, a demonic image, with the ark atop Mount Ararat, the symbol of the end of the flood.

These details of Frye’s interpretation are a direct consequence of his method, depending as it does upon the assumption that the larger framework of correspondences and antitheses are present throughout Milton’s epic. In other words, the cosmology which Frye assumes to be operative throughout Paradise Lost determines the direction of his commentary. Consider, for example, his interpretation of Galileo’s function in Book I:

The references of Galileo are by no means hostile, and it is clear from the use made of him in the argument of Areopagitica that in Milton’s ideal state he would be a highly respected citizen. But if they are not hostile they are curiously deprecatory. Milton seems to regard Galileo, most inaccurately, as concerned primarily with the question of whether the heavenly bodies, more particularly the moon, are habitable—as a pioneer of science fiction rather than of science. As Satan hoists his great shield, the shield, in a glancing parody of the shield of Achilles which depicted mainly a world at peace, is associated with Galileo peering through his telescope at the moon: {168} to descry new lands, Rivers or mountains in her spotty globe. Galileo thus appears to symbolize, for Milton, the gaze outward on physical nature, as opposed to the concentration inward on human nature, the speculative reason that searches for new places, rather than the moral reason that tries to create a new state of mind. (RE, 58)

Now this interpretation depends on Frye’s dialectical division of Milton’s world into the demonic and the “properly human poles.” Galileo’s philosophic vision, which “sees man as a spectator of a theatrical nature” (RE, 59), is rooted in a demonic conception of the cosmos. It is the view of fallen man, pulling humanity away from the vision of liberty because it is attached to the external world and not to the “world within.” For Galileo, Frye says, “the form of God’s creation has been entirely replaced by space, and while he may hope, like Satan, that space may produce or disclose new worlds, there is nothing divine in space that man can now see, nothing to afford him a model of the new world he must construct within himself” (RE, 58).

Whether or not Frye is correct about Galileo’s function is problematic. At least one Miltonist thinks not.9 The point I want to make, however, is that Frye’s interpretation derives from his broad, cosmological perspective. If Milton’s poetic world is hierarchical, then every image he uses must have its appropriate place on one of the levels of existence. If heroic action, defined in terms of man’s proper place in the four orders, is the “paradise within,” then Milton’s imagery must either support the ultimate vision or be a demonic parody of it. Frye follows this kind of reasoning throughout.

We can see Frye “standing back,” as it were, in an effort to grasp the large dialectical patterns. Once these have been found, his usual procedure is to let them determine the direction of his commentary. To illustrate the point again: In The Return of Eden Frye discusses four kinds of heroic action, whereas in an earlier essay he considers only three.10 The reason for the discrepancy is that the earlier essay assumes a three-storied cosmology: Milton’s universe, Frye argues, consists of heaven, earth, and hell; therefore we find three corresponding kinds of action. But in The Return of Eden an additional order makes its way into the Miltonic hierarchy, which means that Frye must locate an additional form of heroic action. In short, the way Frye views Milton’s cosmological framework determines the specific details of his analysis.

In his third chapter Frye turns from the macrocosmic to the micro-cosmic perspective: “In the soul of man, as God originally created it, there is a hierarchy. This hierarchy has three main levels: the reason, {169} which is the control of the soul; the will, the agent carrying out the decrees of the reason; and the appetite” (RE, 60). In an unfallen state—that is, when reason controls the soul—the will is free “because it participates in the freedom of the reason.” “The appetite is subordinate to both, and is controlled by the will from the reason” (RE, 60). Milton accepts this traditional division of the soul, according to Frye. It is implicit in his presentation of Adam and Eve before the fall. And after the fall, the hierarchy which God implants in the soul is reversed . Appetite now assumes the topmost place, Frye says, “and by doing so it ceases to be appetite and is transformed into passion, the drive toward death” (RE, 68-69). Frye does not develop the application of this hierarchy and its reversal. His emphasis rather is upon Milton’s intellectual framework itself, especially as it relates to the fall. And this framework, we come to discover finally, consists not of three levels after all, but of five.

Reason is subordinate to a higher principle than itself: revelation, coming directly from the Word of God, which emancipates and fulfils the reason and gives it a basis to work on which the reason could not achieve by itself. The point at which revelation impinges on reason is the point at which discursive understanding begins to be intuitive: the point of the emblematic vision or parable, which is the normal unit in the teaching of Jesus. The story of the fall of Satan is a parable to Adam, giving him the kind of knowledge he needs in the only form appropriate to a free man. (RE, 74)

Here we have a clear indication of the categories of the Anatomy being put to use, especially those of the Second Essay. The emblematic vision which Milton holds out to Adam is not unlike the anagogic vision in whose presence, according to Frye, the poet and critic become almost indistinguishable. In defining anagogic criticism, we recall, Frye turns to the heightened poetic moments of writers like Blake and Eliot (in the Quartets), whose epiphanic visions of the incarnate Word embody a critical doctrine of the imagination. He does not go quite so far with Paradise Lost, but he does see Milton’s concept of revelation as approaching the Romantic view of the imagination: “for the poet, who has brought his poetic gifts into line with revelation, the same point [i.e., the point of emblematic vision] would be the point of inspiration. Milton does not have exactly the later Romantic conception of imagination, but Keats was right in seeing in Adam’s dream the corresponding conception, a mental image that becomes a reality” (RE, 74). In other words, Milton the poet becomes Milton the anagogic critic, illuminating the nature of what, for Frye, is the highest level of criticism.

{170} At the opposite pole from revelation, so Frye’s argument continues, is still another level in the hierarchical structure of existence lying behind Paradise Lost. “Below the appetite . . . there is a parody of revelation, the fancy or fantasy, the aspect of the mind that is expressed in dreams, including daydreams, and which has the quality of illuminating the appetite from below, as revelation illuminates the reason from above” (RE, 75). The dream of Eve represents this fantasy, “a microscopic example of the upward demonic explosive movement, from chaos into order” (RE, 75). What happens, then, after the fall is that fantasy and revelation are reversed. Fantasy becomes the demonic emblematic vision: it “is now on top illuminating the passion” (RE, 75).

Milton’s conception of the various divisions of the unfallen soul—to summarize Frye’s view of it—would be organized as follows:

- Revelation.

- Reason.

- Will.

- Appetite.

- Fantasy.

After the fall this hierarchy, of course, is reversed. Frye’s chief procedure in the third chapter is to use this model for illuminating Milton’s conception of sin. Behind the discussion, which is primarily doctrinal or theological, we can observe the ever-present method of analogy. To take one example, the “appetite,” before the fall, is represented by hunger and sexual desire. When the soul is inverted, these energies are transformed into greed and lust respectively. By analogy, greed and lust on the demonic level become fraud and force, inward and outward vices, inquisition and indulgence, excess and mechanical repetition (RE, 68-78). In other words Frye keeps altering, or at least expanding, the meaning of his terms, depending on whether he is examining the behavior of Adam and Eve or of human society, and on whether the examination relates to a prelapsarian or postlapsarian state.

Frye devotes all this attention to Milton’s conceptual universe because he believes the structure of Paradise Lost depends on it. “If we knew nothing of Milton except Paradise Lost,” he says at one point, “we should still be aware that the structure was supported by a powerful and coherent skeleton of ideas” (RE, 82), which is to say that the poem is primarily a “thematic” work. But at the same time Paradise Lost contains “fictional” elements. Frye does not actually use the fictional-thematic terminology, speaking rather of the two interests as “dramatic” and “conceptual.” But the difference is the same. In fact, one of the issues he confronts is the relationship of these two interests in Paradise Lost. Sometimes he takes the view that the tension between the dramatic {171} and conceptual emphases is deliberate on Milton’s part and necessary to the structure of the entire poem. He says, for example, that after the fall

Adam is motivated by his desire to live with Eve and his feeling that he cannot live without her. Conceptually and theologically he is entirely wrong. . . . He should have “divorced” Eve at the moment of her fall. But. . . the conceptual and theological situation is not the dramatic one. Adam’s decision to die with Eve rather than live without her impresses us, in our fallen state, as a heroic decision. We feel a certain nobility in what Adam does: Eve also feels this and expresses it. (RE, 79)

Yet, Frye concludes, the sense of this contrast between the fictional and the thematic aspects of the poem is necessary: it satisfies our feelings of what is appropriate for Adam to do, and it fits the structure of the Christian myth and its classical precedents (RE, 79).

At other times, however, Frye takes the view that the dramatic and conceptual aspects of the poem are simply inconsistent, as in the speech of God in Book Three:

[When] God the Father, in flagrant defiance of Milton’s own theology, which tells us we can know nothing about the Father except through the human incarnation of the Son, does speak, [it is] with disastrous consequences. The rest of the poem hardly recovers from his speech, and there are few difficulties in the appreciation of Paradise Lost that are not directly connected with it. Further, he keeps on speaking at intervals, and whenever he opens his ambrosial mouth the sensitive reader shudders. Nowhere else in Milton is the contrast between the conceptual and dramatic aspects of the situation . . . so grotesque: between recognizing that God is the source of all goodness and introducing God as a character saying: “I am the source of all goodness.” The Father observes the improved behaviour of Adam after the fall and parenthetically remarks: “my motions in him.” Theologically, nothing could be more correct: dramatically, nothing is better calculated to give the impression of a smirking hypocrite. (RE, 99)

More often than not, however, Frye’s attention is focused less on the details of the dramatic situation than on Milton’s larger thematic vision. This vision is central to Frye’s main argument about Paradise Lost. It concerns the imaginative return of Eden, that internal paradise emblematic of the free intelligence. The theme receives its fullest treatment in Frye’s fourth chapter. But in the other four chapters, {172} especially toward the conclusion of each of them, Frye manages to relate this theme to whatever his special topic happens to be. He relates it to Milton’s concept of heroic action in the first chapter and to the speculative reason of Galileo’s philosophic gaze in the second. In the heavily doctrinal third chapter the major theme returns once again, this time in relation to Milton’s view of the Mosaic code. Milton conceives of Mosaic law as “a higher gift than moral law, because it prevents morality from becoming an end in itself. Its meaning is typological, the acts it enjoins being symbols of the spiritual truths of the gospel. Hence it corresponds in society to what we have called the emblematic vision in the individual, the point at which reason begins to comprehend revelation” (RE, 84).

In the fourth chapter Frye analyzes this emblematic vision as it relates to the revolutionary nature of Milton’s art. The argument, briefly, is this: True liberty for Milton will come not through political or social action but through revelation. Milton is a revolutionary artist insofar as he discards external and historical conceptions of liberty in favor of an internal and visionary freedom. “Everything Milton associates with liberty is discontinuous with ordinary life. . . . The source of liberty is revelation: why liberty is good for man and why God wants him to have it cannot be understood apart from Christianity” (RE, 96). Where, in Milton’s perspective, is man to obtain such a vision? “Not from the nature outside us,” answers Frye, “because . . . the fall of man was the fall of Narcissus, and what we see in nature is like ourselves. It can only come from something inside us which is also totally different from us. That something is ultimately revelation, and the kernel of revelation is Paradise, the feeling that man’s home is not in this world, but in another world (though occupying the same time and space) that makes more human sense” (RE, 97). Or again: “In Paradise Lost . . . it is Paradise itself that is internalized, transformed from an outward place to an inner state of mind. . . . The heaven of Paradise Lost, with God the supreme sovereign and the angels in a state of unquestioning obedience to his will, can only be set up on earth inside the individual’s mind” (RE, 110-11).

It is obvious that Frye’s Romantic aesthetic helps to shape his central thesis about Milton. He is most captivated by that aspect of Milton’s work which, to use the language of the Anatomy, approaches the imaginative limits of desire. By emphasizing Milton’s mythopoeic vision, Frye locates him among those liberal and Romantic writers, like Blake, whose view of the imagination is consistent with his own. “Milton’s ‘liberty,’ ” he says in Fearful Symmetry, “is practically the same as Blake’s imagination” (FS, 159). Many statements in The Return of Eden, if taken out of context, sound as if they might have come from Fearful Symmetry. {173} Milton, like Blake, is for Frye a fifth-phase symbolic poet. “We have got far enough with Paradise Lost,” he says toward the end of his fourth chapter, “to see that we have to turn the universe inside out, with God sitting within the human soul at the centre and Satan on a remote periphery plotting against our freedom. From this perspective, perhaps, we can see what Blake meant when he said that Milton was a true poet and of the devil’s (i.e., revolutionary) party without knowing it” (RE, 112-13). In another essay Frye observes that the revolutionary aspect of Milton’s art “shows how near he is to the mythology of Romanticism and its later by-products, the revolutionary erotic, Promethean, and Dionysian myths of Freud, Marx, and Nietzsche.”11

We began by observing that Frye’s discussion is influenced by his dyadic framework of mythos and dianoia. The thrust of his argument derives from the ideas associated with the latter of these categories: the structure of Milton’s imagery; his conceptual universe; and his thematic emphasis, which is “the garden within.” But Frye also conceives of Milton’s work in terms of mythos. On the one hand, he envisions the narrative of Paradise Lost as an episodic sequence. Milton invites us to read the events of his poem not as a great cycle of cause and effect but “as a discontinuous series of crises” (RE, 102). “At each crisis of life the important factor is not the consequences of previous actions, but the confrontation, across a vast apocalyptic gulf, with the source of deliverance. So whatever one thinks of the Father’s argument, some argument separating present knowledge and past causation is essential to Milton’s conception of the poem” (RE, 103). On the other hand, when Frye looks at Milton’s work as a whole, he sees it comprising a total cyclical action. Thus he views the epics not simply as a vast symmetrical ordering of themes and images but also as an equally vast narrative movement. In the Anatomy he calls this the “central unifying myth” (AC, 192), or the total action of literature comprised by the four mythoi. His own version of this monomyth is an expansive, cyclical narrative of exile, quest, and return. Frye does not provide a detailed application of his theory of mythos to Milton’s work. But it is clear that he views the two epics as separate parts of a total action which begins and ends “not at precisely the same point, but at the same point renewed and transformed by the heroic action itself” (RE, 14). Transformation comes about by man’s quest, which for Milton is an interior journey. It is a quest for the recovery of that vision of freedom man possessed in Eden before the fall. And the narrative movement of Milton’s epics, Frye believes, is directed precisely toward this renewal of man’s true identity: “To use terms which are not Milton’s but express something of his altitude, the central myth of mankind is the myth of lost identity: the goal of all reason, courage, and vision is the regaining of identity. The {174} recovery of identity is not the feeling that I am myself and not another, but the realization that there is only one man, one mind, one world, and that all walls of partition have been broken down forever” (RE, 143). These are the concluding words to The Return of Eden, and they indicate, more clearly perhaps than anywhere else in the book, Frye’s view of Milton as a Blakean visionary, the understanding of whom depends ultimately on anagogic criticism.

The study of conventions and genres, Frye says in the Anatomy, is the basis of archetypal criticism (AC, 99), the principles of which are outlined in the Third and Fourth Essays of that book. I have been attempting to show how he applies these principles in his study of Milton. It is not always easy to distinguish the biographical and historical from the archetypal approaches in The Return of Eden. And yet the study as a whole remains a work of archetypal criticism insofar as Frye is interested primarily in Milton’s use and adaptation of conventional literary forms and imagery, of conventional cosmologies and myths.

The same interest directs Frye’s other studies of Milton. In “The Revelation to Eve” (SS, 135–59) he examines Milton’s imagery in terms of “two great mythological structures on which the literature of our own Near Eastern and Western traditions has been founded” (SS, 158). One structure is dominated by the masculine father principle with its emphasis on the rational order of nature; the other is dominated by the female-goddess archetype, with its stress on the mystery of Eros. The father-god archetype is inherently conservative, while the mother-goddess archetype is Romantic, revolutionary, and Dionysian. Milton, according to Frye, understood the claims of both of these mythical structures on the imagination, and Frye uses the dreams of Adam and Eve in Paradise Lost to illustrate the way Milton holds them in tension.

Frye’s other essay on Milton, “Literature as Context: Milton’s Lycidas” (FI, 119–29), is an excellent example of his theoretical principles applied to a single poem. He seeks to relate Lycidas, first of all, to the conventions of the pastoral elegy, which involves him in a discussion of such things as the dying-god imagery of the Adonis lament and its association with the cyclic imagery of nature, the “sanguine flower” archetype, and the archetypes of the poet (Orpheus) and the priest (Peter). He also sets the poem against the background of the four-storied framework of Renaissance imagery, showing how Lycidas is connected with each of the levels of existence. Frye himself summarizes the principles that guide his discussion:

In the writing of Lycidas there are four creative principles of particular importance. To say that there are four does not mean, of course, that they are separable. One is convention, the {175} reshaping of the poetic material which is appropriate to this subject, Another is genre, the choosing of the appropriate form. A third is archetype, the use of appropriate, and therefore recurrently employed, images and symbols. The fourth, for which there is no name, is the fact that the forms of literature are autonomous: that is, they do not exist outside literature. (FI, 123)

To these structural and generic principles we should add a fifth, for Frye goes on to argue that the structure of Lycidas as a whole is informed by myth, specifically the Adonis myth. He says, in fact, that the structure of Milton’s poem is the Adonis myth: “It is in Lycidas in much the same way that the sonata form is in the first movement of a Mozart symphony. It is the connecting link between what makes Lycidas the poem it is and what unites it to other forms of poetic experience” (FI, 127). In other words, myth as a structural principle is what holds together the unique and the conventional tendencies in the poem.

Studies of Literary Periods

Frye’s several essays in literary history are also based on the application of principles and assumptions laid down in the Anatomy. We will consider two of these studies, each of which employs a separate method and depends upon a distinctive set of assumptions.

The Age of Sensibility The first is an essay entitled “Towards Defining an Age of Sensibility” (FI, 130–37). Although a brief study, it is a classic example of Frye’s use of the Aristotelian versus the Longinian approach. His aim is to define the period of English literature covering roughly the last half of the eighteenth century. His method depends on the assumption that “in the history of literature we become aware, not only of periods, but of a recurrent opposition of two views of literature. These two views are the Aristotelian and the Longinian, the aesthetic and the psychological, the view of literature as product and the view of literature as process” (FI, 130–31). These pairs of opposites are the basis for Frye’s study in contrast. On the Aristotelian side of the dichotomy he locates those writers and literary tendencies which preceded the Age of Sensibility; and on the Longinian side, those of the post-Augustan age itself. These broad distinctions are refined in the course of Frye’s discussion.

What does it mean to say one age views literature as product, another as process? For Frye it means that in the area of prose fiction, to take his first example, the typical question we ask about (say) a Fielding novel is, “How is this story going to turn out?” The emphasis, {176} in other words, is on the novel as a finished product: “The suspense is thrown forward until it reaches the end, and is based on our confidence that the author knows what is coming next” (FI, 131). But in writers like Richardson, Boswell, and especially Sterne our interest, Frye says, is focused not upon what is coming next in the story but upon what the author will think of next. In the case of Sterne, for example, “we are not being led into a story, but into the process of writing a story” (FI, 131). Similarly, in Richardson and Boswell our interest is in the continuous process of experience in the present.

The dichotomy between product and process is also apparent, he argues, in the poetry of the two periods. In Pope’s verse, for example, the sense of a finished product greets us in the regularly recurring meter of the heroic couplet and in the continually fulfilled expectations of sound and sense. But in the succeeding period “we get something of the same kind of shock that we get when we turn from Tennyson or Matthew Arnold to Hopkins. Our ears are assaulted by unpredictable assonances, alliterations, interrhymings, and echolalia” (FI, 132). These intensified sound patterns, which we find in such poets as Smart, Chatterton, Burns, Ossian, and Blake, are a result, Frye maintains, of an interest in poetry as process; they are close to the primary stage of poetic composition where free association predominates.

Frye proposes a whole list of opposites which might be used to differentiate these two interests: conscious versus unconscious control, regular versus irregular meter, concentration of sense versus diffusion of sense, epigrammatic versus incantatory quality, wit versus dream, continuous versus discontinuous lyrics, clarity of syntax versus fragmentary utterances, and so on (FI, 133–34).

A third opposition Frye uses is one we have already met in the First Essay of the Anatomy.12 This is the distinction between the aesthetic and the psychological reaction of the reader to the emotions of pity and fear.

Where there is a strong sense of literature as aesthetic product, there is also a sense of its detachment from the spectator. Aristotle’s theory of catharsis describes how this works for tragedy: pity and fear are detached from the beholder by being directed towards objects. Where there is a sense of literature as process, pity and fear become states of mind without objects, moods which are common to the work of art and the reader, and which bind them together psychologically instead of separating them aesthetically.13

Although Frye does not say so, he implies that in the Age of Pope aesthetic detachment is the typical response. In any case, all of his {177} attention is directed toward defining what it means to say that in the Age of Sensibility fear and pity are emotions without objects. “Fear without an object, as a condition of mind prior to being afraid of anything, is called Angst or anxiety, a somewhat narrow term for what may be almost anything between pleasure and pain” (FI, 135). Frye finds the source of this kind of reaction in the eighteenth-century conception of the sublime, with its qualities of “austerity, gloom, grandeur, melancholy, or even menace.” Such qualities produce romantic or penseroso emotions, which are the basis of appeal in Ossian and “graveyard” poetry, in Gothic novels and tragic ballads, and in “such fleurs du mal as Cowper’s Castaway and Blake’s Golden Chapel poem” (FI, 135).

Pity without an object, on the other hand, “expresses itself as an imaginative animism, or treating everything in nature as though it had human feelings or qualities” (FI, 135). Frye is able to isolate four types of this state of mind or mood: (1) the apocalyptic celebration of nature, as in Smart’s Song of David and the ninth Night of Blake’s The Four Zoas; (2) imaginative sympathy with the folklore of elemental spirits, as in Collins, Fergusson, Burns, and the Wartons; (3) intense awareness of the animal world, as in Burns’s To a Mouse, Cowper’s snail poem, Smart’s lines on his cat, the starling and ass episodes in Sterne, and Blake’s opening to Auguries of Innocence; and (4) sympathy with man himself, as in the protests against slavery and misery in Cowper, Crabbe, and Blake (FI, 135).

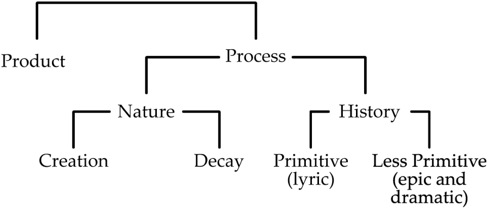

When Frye turns to elaborate on the primitive process of writing itself, his method, once again, is that of dichotomous division. It involves three additional sets of subcategories, descending from the “process” side of his main opposition. Figure 24 is a diagram of the three-tiered taxonomy. The primitive process of writing, Frye is saying, can be projected toward one of two poles: nature or history. If projected toward nature, the poetry of sensibility will tend toward one or the other of two additional poles, either the creative or the decaying natural process. In other words the poet will be attracted either by the “primeval and ‘unspoiled’ or by “the ruinous and the mephitic” (FI, 135). On the other hand, the “projection into history assumes that the psychological progress of the poet from lyrical through epic to dramatic presentations . . . must be the historical progress of literature as well. Even as late as the preface to Victor Hugo’s Cromwell this assumption persists. The Ossian and Rowley poems are . . . pseudepigrapha, like the book of Enoch, and like it they take what is psychologically primitive, the oracular process of composition, and project it as something historically primitive” (FI, 135–36).

Figure 24. Literature as process. {p. 178} |

|

Frye’s final point about the “primitive” quality of the Age of Sensibility relates to the poet himself. It is an age, he points out, of the poète {178} maudit. He then connects this personal or biographical quality with “its central technical feature,” the metaphor, drawing upon the principles of analogy and identity we encountered in the Second Essay of the Anatomy:

For Classical and Augustan critics the metaphor is a condensed simile: its real or common-sense basis is likeness, not identity, and when it obliterates the sense of likeness it becomes barbaric. . . . For the Romantic critic, the identification in the metaphor is ideal: two images are identified within the mind of the creating poet. But where metaphor is conceived as part of an oracular and half-ecstatic process, there is a direct identification in which the poet himself is involved. To use [a] phrase of Rimbaud’s, the poet feels not “je pense,” but “on me pense.” (FI, 136–37)

Thus the fundamental metaphoric feature of the Age of Sensibility is neither an analogy nor an equation between two things or images but a psychological identification between the poet himself and something else. These self-identifications of the poète maudit, which work against his social personality, take strange and poignant forms: they may seem “manic, like Blake’s [identification] with Druidic bards or Smart’s with Hebrew prophets, or depressive, like Cowper’s with a scapegoat figure, a stricken deer or castaway, or merely bizarre, like Macpherson’s with Ossian or Chatterton’s with Rowley” (FI, 137). The most complete and intense expressions of this “primitive” self-identification are to be {179} found, Frye says, in Collins’s Ode on the Poetical Character, Smart’s Jubilate Agno, and Blake’s Four Zoas, poems in which “God, the poet’s soul and nature are brought into a white-hot fusion of identity, an imaginative fiery furnace in which the reader may, if he chooses, make a fourth” (FI, 137).

It is certainly not unusual for critics, in their attempts to define literary periods, to refer to the conception which the poet has of himself. In this respect, Frye’s point about the poète maudit is typical of what a historical critic might do. What is highly unexpected, however, is the way Frye goes about doing it: his relating the poet’s personality (a biographical matter) to the technical principle of metaphor (a rhetorical matter) in order to define the “primitive” quality of an age’s poetry. If we ask how all of this relates to Frye’s initial category of literature as process, his answer would be that the typical image we have of the post-Augustan poet is that of an oracle, one who freely associates words in a trancelike state, one who utters rather than addresses; so that our interest is focused—to use his earlier distinction—not upon how the poem is going to turn out but upon what is coming next.

The chief methodological feature of this essay is the deductive manner by which Frye proceeds, for what he does is to establish broad pairs of categories and then use them as a framework for generalizing about the Age of Sensibility. There is nothing particularly striking about his a priori categories: few would disagree that it is possible to view literature both as product and as process, that there are two poles to the natural process, or that some literary works are both historically and psychologically more primitive than others. Rather, the extraordinary feature is the kind of insight that results from the application of the theoretical assumptions. What really defines the Age of Sensibility is not the fact that its literature can be viewed as “process”; this is a commonplace, not a definition. But when Frye applies this principle specifically, working back and forth between his general hypothesis and his inductive survey of literature itself, a meaningful set of defining characteristics does emerge. I said previously that the essay is a study in contrast, by which I meant that Frye defines the Age of Sensibility by differentiating it from the previous and, to a lesser extent, the succeeding ages. And yet, since Frye is seeking to discover the broad “tendencies” and “interests” of the period, his definition does remain highly generalized.14 When we look at the essay as a whole, what stands out is the conceptual breadth which characterizes Frye’s criticism.

Frye’s readers have sometimes questioned the freedom and assurance of his broad categorizing, especially when he seems to be {180} trespassing into their own special fields of competence.15 There seems to be no one, however, who has questioned Frye’s authority in the field of English Romanticism. His book on the subject will be our second example of his studies in literary history.

Romanticism A Study of English Romanticism treats the Romantic movement as primarily a change in the mythological structure of poetry, brought about by various cultural and historical forces. This, in fact, is Frye’s thesis, argued in an introductory chapter entitled “The Romantic Myth.”16 The three remaining chapters, intended to illustrate the thesis, are critical discussions of Beddoes’s Death’s Jest-Book, Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound, and Keats’s Endymion.

Frye claims that Romanticism gives birth to a new mythological structure in Western culture. The argument rests upon his conceptions of myth and mythology, which he summarizes as follows:

The informing structures of literature are myths, that is, fictions and metaphors that identify aspects of human personality with the natural environment, such as stories about sun-gods or tree-gods. The metaphorical nature of the god who is both a person and a class of natural objects makes myth, rather than folktale or legend, the direct ancestor of literature. It also gives to myth, in primitive cultures, a particular importance in establishing a society’s views of its own origin, including the reasons for its divisions into different classes or groups, its legal sanctions, and its prescribed rituals. The canonical significance which distinguishes the myth from less important fictions also causes myths to form large unified structures, or mythologies, which tend to become encyclopedic in extent, covering all aspects of a society’s vision of its situation and destiny. As civilization develops, mythology divides into two main aspects. Its patterns of stories and images, attracting and absorbing those of legend and folktale, become the fictions and metaphors of literature. At the same time, there are also germs of conceptual ideas in myths which extend into theology, philosophy, political theory, and, in earlier ages, science, and become informing principles there as well. (SER, 4–5)

The assumption here is that myths manifest themselves in two ways, artistically and conceptually. On the one hand, literature and other forms of art descend from mythology, inheriting its fictional and metaphorical patterns. One can study these patterns formally, which is what the Anatomy is all about. On the other hand, because myth is related to certain social features in a society, there is a body of ideas which {181} descends from myth. Both the literary and the conceptual forms are a part of what Frye calls a culture’s “total mythological structure”; it “may not be explicitly known to anyone, but is nevertheless present as a shaping principle” (SER, 5). The closest realization we have of this total mythological structure is found in encyclopaedic cultural forms, in literary works like the Commedia and Paradise Lost, and in conceptual works like St. Thomas’s Summa. The total structure in Western culture was for centuries characterized by an encyclopaedic myth derived mainly from the Bible.

It is this mythological structure that Frye sets out initially to define, for his argument depends on showing how the Romantic myth is opposed to the myth which dominated the centuries preceding Romanticism. There are a number of differences between the two mythological structures. First, they are based on different myths of the creation. For pre-Romanticism (i.e., from the beginning of the Christian era down to the last part of the eighteenth century) the creation myth was an “artificial” one in that it assumed “the world was made, as an artefact or creature, by a divine artisan or demiurge” (SER, 6). The idea that the gods are not a part of nature and that man should view nature as evidence for intelligent design gave prominence to subject-object relations and heightened the rational attitude toward the world. The Christian version of the myth postulates that God, man, and nature were once identified, but that man fell and thus broke his harmonious relation with nature. Therefore man’s chief end is to regain his lost identity, and the means for achieving this is through rational and social discipline, that is, through law, morality, and religion. Behind the entire Christian myth lies a dichotomy in which nature is set over against human consciousness: man is assumed to be a social rather than a natural being; he must constantly maintain the barrier between himself and the forces of nature, Eros and Dionysus (SER, 5–10).

But in Romanticism, according to Frye, the subject-object relationship recedes into the background. When we begin reading Wordsworth and Coleridge we discover that “the reason founded on a separation of consciousness from nature is becoming an inferior faculty of the consciousness, more analytic and less constructive, the outside of the mind dealing with the outside of nature; determined by its field of operation, not free; descriptive, not creative” (SER, 12). Frye sees this change as the first important difference between the Romantic and pre-Romantic mythological structures. Blake, who saw the implications of this change more completely than any other English Romantic poet, realized that the god of the older paradigm was “a projected God, an idol constructed out of the sky and reflecting its mindless mechanism” (SER, 13). Thus Blake concluded that if God exists, he exists as an aspect of {182} man’s own identity. Frye sees this recovery of projection as the “one central element of [the] new mythological construction” (SER, 14). “In the older myth,” he says,

God was ultimately the only active agent. God had not only created the world and man: he had also created the forms of human civilization. The traditional images of civilization are the city and the garden: the models of both were established by God before Adam was created. Law, moral principles, and, of course, the myth itself were not invented by man, but were a part of God’s revelation to him. Gradually at first, in such relatively isolated thinkers as Vico, then more confidently, the conviction grows that a great deal of all this creative activity ascribed to God is projected from man, that man has created the forms of his civilization, including his laws and his myths, and that consequently they exhibit human imperfections and are subject to human criticism. (SER, 14)

A second aspect of the imaginative revolution of Romanticism is a splitting away of the scientific vision of nature from the poetic and existential vision. These last two are what Frye calls the “myth of concern,” what society sees as its situation and destiny. And when the myth of concern is separated from science, it becomes an “open” mythology, as distinct from the previous Christian, or “closed,” mythology of compulsory belief. Romanticism, then, ushers in not merely a new myth but a new attitude toward other myths. Moreover, conceiving of mythology as a structure of the imagination changes the spirit of belief: new types of belief are possible (SER, 15–16). Two of these are especially important for Frye’s argument: “One is the revived sense of the numinous power of nature, as symbolized in Eros, Dionysus, and Mother Nature herself” (SER, 16). The second “comes from the ability that Romantic mythology conferred of being able to express a revolutionary attitude toward society, religion, and personal life” (SER, 17).

The first of these means that in Romanticism the older cyclical myth of the Bible from fall to reconciliation assumes a different shape. The old unfallen state becomes the original identity between individual man and nature. The myth of alienation is changed from a fall into sin to a fall into a self-conscious awareness of the subject-object relation to nature: man’s primary conscious feeling is one of separation not from God but from nature. Thus the myth of redemption in Romanticism “becomes a recovery of the original identity” (SER, 18). Redemption proceeds from human-centered eros rather than from divine agape (SER, 20).

The transposition of the older mythology brings with it a {183} revolutionary change in the poet’s social freedom. If t2he poet himself creates the forms of his civilization, then he becomes a central figure who aims not to please but to expand society’s consciousness. The poet, Frye says, gains an authority of his own, completely separate from the moral context of the traditional mythology (SER, 21–22).

Third, Romanticism profoundly alters the traditional schema of four levels of reality. This chain of being includes a divine world, an unfallen world of the proper or original human nature, a lower world of experience (the physical order), and a demonic world of death. As we know from the Anatomy, Frye conceives of this schema both cyclically and dialectically. T he divine and demonic worlds (heaven and hell) are eternally separated, whereas the two middle worlds describe a condition from which man fell and to which, at the end of the historical cycle, he should return. According to Frye it is still possible to think of the mythological structure of Romanticism as a scheme of four levels, but the structure as a whole is much more ambiguous and much less concretely related to the physical world. He says, for example, that in Romanticism

what corresponds to heaven and hell is still there, the worlds of identity and alienation, but the imagery associated with them, being based on the opposition of “within” and “without” rather than of “up” and “down,” is almost reversed. The identity “within,” being not purely subjective but a communion, whether with nature or God, is often expressed in imagery of depth or descent. . . . On the other hand, the sense of alienation is reinforced, if anything, by the imagery of what, since Pascal, has increasingly been felt to be the terrifying waste spaces of the heavens. (SER, 46-47)

Similarly, the worlds of human and physical nature are also present in Romanticism, but their relation is reversed too. In the traditional mythology, social and civilized life was necessary for man’s regaining his identity, whereas in “a great deal of Romantic imagery human society is thought of as leading to alienation rather than identity” (SER, 47). The Romantics most often appeal to the order of nature outside of society as the source for what is creative and healing.

I have been summarizing Frye’s understanding of the chief differences between the two major mythological structures of Western culture. His method of defining Romanticism is to show how three aspects of the older mythology are profoundly transformed. What emerges in the Romantic mythology is a new myth of creation, a new myth of the fall and redemption, and a new understanding of the four-tiered structure of reality. In what respects is Frye’s method different from that {184} which a historian of ideas might follow? My summary of his discussion might suggest that nothing would be much changed if we were to substitute a word like “doctrine,” “idea,” or “conception” for his word ‘myth.” But Frye’s study actually differs from a history of ideas in that mythology for him is never simply the conceptual product of culture. Myths are originally stories, and when they are codified to form a mythology, he says, two cultural products result. One is conceptual, a body of cohering ideas; the other is fictional and metaphorical, a body of artistic patterns and conventions. Frye sees mythology then—to use the language of the Anatomy—as a combination of dianoia and mythos. When he defines the myth of creation, for example, it is not only in terms of a set of concepts, like the relationship between God, man, and nature, but also in terms of imagery and story. More important than this, however, is the fact that even when Frye uses “myth” as a synonym for “idea,” he does not primarily mean “idea” as an object of belief but “idea” as part of a structure of imagery. Conceptually, the Romantic myth is mainly fictional, an imaginative construct, a spatial projection of reality. “For the literary critic,” Frye says, “the word Romanticism refers primarily to some kind of change in the structure of literature itself, rather than to a change in beliefs, ideas, or political movements reflected in literature” (SER, 4).

The remainder of Frye’s book is devoted to an analysis of the three English Romantic works already mentioned. Frye’s commentary, however, is not primarily directed toward an interpretation of the works themselves, even though much of what he says would be useful in developing an interpretation. Rather, the three writers are used to illustrate Frye’s conception of Romanticism: his commentary exists for the sake of the theory rather than vice versa. “Any reader who finds [my] approach to these poets somewhat peripheral,” Frye says, “is asked to remember that this is not a book on Beddoes or Keats or Shelley, but a book on Romanticism as illustrated by some of their works.”17

I have called Frye’s book on Romanticism a study of literary history in order to help distinguish among his several kinds of applied criticism. Yet Frye sees “Romanticism” as both more than and less than a term referring to a literary period. It is a cultural as well as a literary term, even though it is not used to characterize all the products of culture between, say, 1780 and 1830. It hardly occurs to us, as Frye points out, to speak of a Romantic movement in the history of science (SER, 3–4). To see “Romanticism” as a cultural term means then that it has its center of gravity in the creative arts, which distinguishes it from a more general historical term like “medieval.” But Frye does maintain that Romanticism has a historical center of gravity as well, a period of {185} about fifty years beginning in England around 1780.18 It is therefore appropriate to call Frye’s work a study in literary history insofar as (1) he is concerned mainly with the literary implications of the term Romanticism, and (2) he believes the term characterizes a new sensibility which comes into Western culture during the last part of the eighteenth century.

Frye’s method for defining this new sensibility rests upon principles which are by now familiar. First, there is the principle of opposition, represented by the broad historical dialectic of the traditional mythological structure versus the Romantic one. Second, there is Frye’s assumption that literature can be viewed spatially, as a static structure of imagery, and temporally, as a narrative movement in time. In the Anatomy Frye’s discussion of the meaning of imagery (Third Essay) is set against the background of the orders-of-reality or levels-of-existence model. He follows the same procedure, as we have seen, in his study of English Romanticism, showing how the older model is reversed by the newer one. Also in the Anatomy Frye analyzes the narrative aspect of literature (its mythoi) in terms of a total mythic pattern stretching from creation to apocalypse. In the present work we see this general principle applied in his analysis of the differences between the two “total mythological structures.” Third, there are Frye’s assumptions about the inherent relationship between literature and myth, assumptions such as the following: the permanent significance of myth is reflected in literature; poetry descends ultimately from myth; both the form and content of myth are subjects of critical study; the social function of mythology is to provide men with an imaginative vision of the human situation, and so on.

These are the three main ways in which A Study of English Romanticism is an application of theoretical assumptions which Frye brings to his subject matter. His method consists in applying these assumptions to two large bodies of mythological (fictional and conceptual) data. The exposition which results, while ranging from prehistory to the twentieth century, is a rather complete account (in forty-six pages) of the differences between the Romantic myth and its predecessors. Certainly one of the values of Frye’s study is its demonstration that Romanticism is not a chaotic age of relativism and subjectivity or a period of contradictory tendencies which follows the breakup of the Great Chain of Being but a consistent imaginative structure in its own right. The essay is a substantive piece of work, deserving a place alongside the efforts of Wellek, Lovejoy, Abrams, and Peckham to define Romanticism. One of the essay’s values is that the work of a largely overlooked writer like Beddoes can be brought properly into focus. Beddoes’s preoccupation with death as an imaginative realm outside the world of experience {186} permits us to see him, according to Frye, as a central, even potentially a major, figure of English Romanticism: “Beddoes revolves around the heart of Romantic imagery, at the point of identity with nature of which death is the only visible form” (SER, 48). Thus he is not simply a “morbid” writer whose place is somewhere on the fringes of the Romantic myth. Frye’s study, in short, provides the kind of background necessary for understanding a writer like Beddoes.19

The Social Context of Criticism