Northrop Frye & Critical Method

Robert D. Denham

Chapter 4: Theory of Genres

Chapter Sections:

Rhetorical Criticism

Generic Rhythm

Style

Generic Forms

Rhetorical Criticism

“The problem of convention,” Frye says in the Second Essay, “is the problem of how art can be communicable. . . . As the archetype is the communicable symbol, archetypal criticism is primarily concerned with literature as a social fact and as a mode of communication. By the study of conventions and genres, it attempts to fit poems into the body of poetry as a whole” (AC, 99). Frye’s description of these conventional and generic modes of communication is found in the Third and Fourth Essays, the latter of which is entitled “Rhetorical Criticism.” Rhetorical issues are raised throughout the First Essay. In the sense, then, that modes of communication have traditionally been located in the province of rhetoric, each of the first three essays is concerned to some degree with the anatomy of rhetorical conventions. When we come to the Fourth Essay, however, this highly general observation must give way to the more restricted issues of what is specifically called “rhetorical criticism” and of its relation to Frye’s theory of genres. In pursuing these topics we have the advantage of the framework Frye sketches at the beginning of the Fourth Essay. It indicates the place of rhetoric in his system as a whole and outlines his distinction between persuasive and ornamental rhetoric, the latter of which is his chief concern.

The far-ranging framework, which recapitulates the view of art proposed in the Anatomy, is based upon the age-old division of reality into three categories, described variously as thought, action, and passion, or truth, goodness, and beauty. In this division, Frye says,

the world of art, beauty, feeling, and taste is the central one, and is flanked by two other worlds. One is the world of social action and events, the other the world of individual thought and ideas. Reading from left to right, this threefold structure divides human faculties into will, feeling, and reason. It divides the mental constructs which these faculties produce into history, art, and science and philosophy. It divides the ideals which form {89} compulsions or obligations on these faculties into law, beauty, and truth. (AC, 243)

What Frye calls the “diagrammatic framework” of these triads is presented in Figure 14.

Figure 14. Triadic framework of Anatomy of Criticism. {p. 90} |

|||

| Three Worlds of “Good” in Anatomy of Criticism | Social Action and Events |

Art, Beauty, Feeling, Taste |

Individual Thoughts and Ideas |

| Human Faculties | Will |

Feeling |

Reason |

| Mental Constructs | History |

Art |

Philosophy, Science |

| Ideals | Law |

Beauty |

Truth |

| Poe’s Schema | Moral Sense |

Taste |

Pure Intellect |

| First Three Aristotelian Elements | MYTHOS: Verbal Imitation of an Action |

ETHOS: Human Nature and Human Situation |

DIANOIA: Verbal Imitation of Thought |

| Categories of the Second Essay | Event |

Idea |

|

Example |

Poetic Symbol |

Precept |

|

Ritual |

Dream |

||

| Second Three Aristotelian Elements | Melos |

Lexis Lexis |

Opsis |

| Pound’s Schema | Melopoeia |

Logopoeia |

Phanopoeia |

| The “Trivium” | Grammar: Narrative or Right Order |

Rhetoric |

Logic: Produced Sense |

A glance at the chart will indicate how the special terminology Frye has employed up to this point falls neatly into the triadic schema: using the method of analogy, he can conveniently fit mythos, ethos, and dianoia into the diagram. Ethos, as Frye has defined the term, stands at the center, flanked on one side by the verbal imitation of action (mythos) and on the other by the verbal imitation of thought (dianoia). Similarly, the poetic symbol finds its place in the framework midway between event and idea, example and precept, ritual and dream—all of which were used in the Second Essay to define the phases of symbolism.

But Frye also recognizes a second aspect of the same triadic scheme, corresponding to the last three qualitative parts of Aristotle’s analysis of tragedy: music, diction, and spectacle. He develops this threefold division in another series of analogies:

The world of social action and event, the world of time and process, has a particularly close association with the ear. The ear listens, and the ear translates what it hears into practical conduct. The world of individual thought and idea has a correspondingly close association with the eye, and nearly all our expressions for thought, from the Greek theoria down, are connected with visual metaphors. Further, not only does art as a whole seem to be central to events and ideas, but literature seems in a way to be central to the arts. It appeals to the ear, and so partakes of the nature of music, but music is a much more concentrated art of the ear and of the imaginative perception of time. Literature appeals to at least the inner eye, and so partakes of the nature of the plastic arts, but the plastic arts, especially painting, are much more concentrated on the eye and on the spatial world. . . . Considered as a verbal structure, literature presents a lexis which combines two other elements: melos, an element analogous to or otherwise connected with music, and opsis, which has a similar connection with the plastic arts. (AC, 243–44)

This second series of triads comprises what Frye sees as the rhetorical aspect of literature, one which “returns us to the ‘literal’ level of narrative and meaning” (AC, 244). We recall not only that Frye frequently equates rhetorical criticism with the procedures of the New Critics but also that he establishes, in the Second Essay, a correspondence between these procedures and the literal phase of symbolism.1

{90} Frye also defines rhetoric by means of the traditional “trivium,” locating it midway between grammar and logic. The definition arises from an analogy between mythos and grammar on the one hand and between dianoia and logic on the other. “As grammar may be called the art of ordering words,” Frye observes, “there is a sense—a literal sense—in which grammar and narrative are the same thing; as logic may be called the art of producing meaning, there is a sense in which logic and meaning are the same thing” (AC, 244). In this view, grammar is “understood primarily as syntax or getting words in the right (narrative) order,” whereas logic is “understood primarily as words arranged in a pattern with significance” (AC, 244–45). Rhetoric, because of its central position in this framework, synthesizes grammar and logic, just as lexis performs the same function in relation to melos and opsis. Frye translates lexis as “‘diction’ when we are thinking of it as a narrative sequence of sounds caught by the ear, and as ‘imagery’ {91} when we are thinking of it as forming a simultaneous pattern of meaning apprehended in an act of mental ‘vision’” (AC, 244). Lexis, in fact is rhetoric, or rather ornamental as distinct from persuasive rhetoric. Similarly, if we consider grammar as the art of ordering words and logic as the art of producing meaning, then literature “may be described as the rhetorical organization of grammar and logic” (AC, 245). The affinity between diction as a narrative sequence and mythos, on the one hand, and imagery as a pattern of meaning and dianoia, on the other, should not go unnoticed.

These definitions of rhetoric are quite inclusive and operate at a high level of generality. But the broad distinctions, especially the relationship of verbal pattern to music and spectacle, figure importantly in the theory of genres, serving to differentiate, for example, among the four kinds of literary rhythm (about which more later). Before turning to the organization of Frye’s theory of genres, I want to make explicit his distinction between ornamental and persuasive rhetoric. “These two things,” he says, “seem psychologically opposed to each other, as the desire to ornament is essentially disinterested, and the desire to persuade is essentially the reverse” (AC, 245). This is a distinction of ends, or a difference between final and instrumental value. Thus the movement of ornamental rhetoric is seen as centripetal, acting upon its hearers statically and producing the admiration of beauty and wit for its own sake, whereas the movement of persuasive rhetoric is centrifugal, leading the audience “kinetically toward a course of action.” The former “articulates emotion; the other manipulates it” (AC, 245). Frye’s concern is chiefly, though by no means exclusively, with ornamental rhetoric, which he equates, as already noted, both with the lexis of poetry and finally with the hypothetical structure of literature itself.

The basic organization of the Fourth Essay derives from what Frye, following Coleridge, calls “initiative,” or the “controlling and coordinating power” which “assimilates every thing to itself, and finally reveals itself to be the containing form of the work.”2 The initiative is comprised of four separate categories: the theme; the unity of mood which determines imagery; the meter, or integrating rhythm; and the genre. This complex of factors, Frye asserts, governs the process of poetic composition. He has treated the first two initiatives in his discussion of archetypal images and narratives in the Third Essay. The remaining two, rhythm and genre, are the controlling ideas of the Fourth.

Although within the larger diagrammatic framework Frye’s definition of rhetoric is general, it has a more specialized and traditional reference as it relates to the fourth factor of a writer’s initiative (the genre). “The basis of generic criticism.” he says “is rhetorical, in the {92} sense that the genre is determined by the conditions established between the poet and his public” (AC, 247). Frye calls this rhetorical element the radical of presentation, by which he means the fundamental, original, or ideal way in which a literary work is presented. The radical of presentation of fiction, for example, is the book or printed page; for drama, it is enactment by hypothetical characters.3 In the last section of his “Introduction” to the Fourth Essay, Frye sketches the relationship among the author, the audience, and the radical of presentation for each of his four generic categories—drama, epos, fiction, and lyric. He also specifies for each genre both a predominant rhythm and a mimetic form. These relationships are summarized in Figure 15.

| Drama | Epos | Fiction | Lyric | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Figure 15. The generic differentiae. {p. 92} | ||||

| Radical of Presentation | Enactment by hypothetical characters |

Oral address |

Book or printed page |

Hypothetical form of I–thou relationship |

| Author or Poet | Poet concealed from audience |

Speaking poet |

Poet as person disappears |

Poet speaking to himself, God, muse, etc. |

| Audience | Observers–listeners as group |

Listeners as group |

Reader as individual |

Poet has his back to audience, which overhears |

| Mimetic Form | External mimesis (outward representation of sound & imagery) |

Mimesis of direct action |

Mimesis of assertion |

Internal mimesis (inward representation of sound & imagery) |

| Rhythm | Rhythm of decorum: appropriateness |

Metric rhythm: recurrence |

Semantic rhythm: continuity |

Oracular rhythm: association |

“Radical of presentation,” “predominant rhythm,” and “mimetic form” are, therefore, the three primary categories used to distinguish the four genres. Only one of these concepts, however, is extensively used in the remainder of the Fourth Essay. It seems clear that Frye wants to establish a relationship, on the one hand, between rhythm and the organization of melos-lexis-opsis, and on the other hand, between the radical of presentation and the mimetic form of each genre. The first {93} of these relationships is clearly developed: in what is perhaps Frye’s most original contribution in the entire essay, he shows that the rhythm of each genre has its characteristic melos and opsis. The second relationship, however, after it has been used to differentiate the four genres, almost completely disappears in the discussion of generic forms, as we shall see when we look at the principles Frye uses to distinguish the specific forms of each genre.

To summarize the several conclusions which can be drawn from Frye’s initial framework of categories: first, “rhetoric” is used in two distinct senses, closely paralleling the two rhetorical concerns in the First Essay. Ornamental rhetoric, the lexis of poetry, is an internal, centripetal category, similar to the rhetorical principle underlying the concept of “fictional modes.” But rhetoric in the second sense, defined as the radical of presentation, is analogous to the ethical relationship between poet and audience which Frye has used to define “thematic modes.”

Second, the main function which the second rhetorical category serves is to define the four genres: rhythm, form, and the radical of presentation provide the generic differentiae. And the main function served by the first rhetorical category (the organization of melos, lexis, and opsis) is to provide principles for an ingenious discussion of generic rhythm. This first category has the additional function of helping to differentiate the various rhythms; the rhythm of epos, for example, is distinguished not only by the comparatively regular meter of recurrence but also by the peculiar rhetorical manifestations of melos and opsis, such as onomatopoeia.

Third, rhetoric in the second sense is essentially a matter of style. Frye is not primarily a stylistic critic. But his discussion of rhythm is the one place in the Anatomy where he does turn to what Angus Fletcher calls the microstructure of literature, the effects of individual lines and phrase units.4

We should hardly expect, in reading an essay on rhetorical criticism, to encounter the unlikely combination of so particular a topic as prosody with so general a one as genre. But to turn from a discussion of poetic phrase units to a topic like the specific continuous forms of prose fiction is characteristic of Frye’s ingenuity. It is because he sees all literature in its relation to other literature that he can move from the microscopic to the macroscopic levels without so much as casting a glance at the countless rhetorical concerns that lie somewhere in between. The point to be made is that Frye is writing a theory of criticism rather than a manual of style; thus his aim is to show how the concerns of stylistic criticism can fit within his synoptic view. Moreover, he sees the New Criticism as having adequately treated the texture of literary {94} rhetoric. Perhaps the more important conclusion is that, by using the radical concept of rhythm in its smallest and largest senses, Frye forces us to see the integral relationship between two very different literary phenomena, both of which call for a social response. Frye’s theory of rhetoric, finally, is one which unites style and genre—a point I intend to illustrate now by turning to an analysis of the four genres.

Frye’s definitions of the genres should not be understood as absolute or mutually exclusive categories into which any work can be neatly fitted. The purpose of generic criticism, he argues, is not so much to classify as it is to clarify “traditions and affinities, thereby bringing out a large number of literary relationships that would not be noticed as long as there were no context established for them” (AC, 247–48). One of the main contexts is the radical of presentation. But since this expression refers only to the way in which works of literature were originally or ideally presented, we can expect many works to fit into more than one category. It is less important, Frye says, to worry about how to classify, say, a Conrad novel, where the narrative technique involves both the written and spoken word, than it is to recognize that this novel embodies two different radicals of presentation (AC, 247). Similarly, “the novels of Dickens are, as books, fiction; as serial publications in a magazine designed for family reading, they are still fundamentally fiction, though closer to epos. But when Dickens began to give readings from his own works, the genre changed wholly to epos; the emphasis was then thrown on immediacy of effect before a visible audience” (AC, 249). The point is that genres are based on conventions; and while it is convenient for Frye’s argument to isolate four possible relations by which writers can communicate to their audiences, the history of literature, with its novels and closet dramas, shows that a given work does not always rely upon a single generic convention.

Characteristic rhythm and predominant form are the two principles underlying the arrangement of the Fourth Essay. Frye first explains the typical pattern of movement characteristic of the genres and then isolates their specific forms. My aim at this point is to uncover the argument behind the abstract rhetorical terminology just outlined.

Generic Rhythm

Epos The characteristic rhythm of epos, defined as that genre where the radical of presentation is oral address (or the mimesis of direct address), is a comparatively regular meter (AC, 250). Frye’s treatment of this kind of rhythm is essentially a commentary on English prosody. This observation should be qualified, however, by saying that he is not so much interested in the linguistic or literary details of prosody as he is in {95} the broader theoretical similarities between the rhythm and pattern of epos, on the one hand, and melos and opsis, on the other. His argument begins with a series of metrical illustrations, used to support his thesis that the four-stress line “seems to be inherent in the structure of the English language” (AC, 251). By isolating stress as the primary constitutive principle of poetic rhythm, Frye throws the emphasis upon intensity and duration, the quantitative aspects of sound. There are several ways, however, of accounting for these two factors in the study of versification. That is, rhythm can be defined by counting the number of syllables to a line, or the number of accents, or by noting the specific temporal measure of a line. But Frye, as his illustrations indicate, relies primarily on stress, his concern being to show the number and disposition of accents within a line. This leads to the crux of his argument: the analogy between music and poetry. In those kinds of music which have been contemporary with all stages of modern English poetry (i.e., anything after Middle English), “we have had almost uniformly a stress accent, the stresses marking rhythmical units (measures) within which a variable number of notes is permitted” (AC, 255). Therefore, when stress accent predominates in poetry, it is “musical” poetry, in the sense that its structure resembles the music contemporary with it. “This technical use of the word musical,” Frye adds,

is very different from the sentimental fashion of calling any poetry musical if it sounds nice. In practice the technical and sentimental uses are often directly opposed, as the sentimental term would be applied to, for example, Tennyson, and withdrawn from, for example, Browning. Yet if we ask the external but relevant question: Which of these two poets knew more about music, and was a priori more likely to be influenced by it? the answer is certainly not Tennyson. (AC, 255)

Frye thus concludes that the word “musical”—Aristotle’s melos—is more properly used as a critical term to describe the “cumulative rhythm” (AC, 256, 258) produced by a variable number of syllables between sharp stresses. Cumulative rhythm yields the “harsh, rugged, dissonant poem” (AC, 256). “When we find sharp barking accents, crabbed and obscure language, mouthfuls of consonants, and long lumbering polysyllables, we are probably dealing,” Frye says, “with melos, or poetry which shows an analogy to music, if not an actual influence from it” (AC, 256). In addition to Browning, Frye includes Burns, Smart, Crashaw, Cowley, Skelton, Wyatt, and Dunbar among the musical poets. On the other hand, poets of the “metronome beat” (AC, 256), those who strive to achieve slow movement, balanced sounds, regular meter, and resonant rhythms, are unmusical poets, or they are musical {96} only in the sentimental sense. Frye’s examples of this type, in addition to Tennyson, include Pope, Keats, Spenser, Surrey, Gray’s Pindarics, Arnold’s Thyrsis, and Herbert’s stanzaic poems (AC, 257).

Recounting the stages of Frye’s argument, we see that he begins by defining epos as that genre in which the poet speaks to his listeners as a group by means of a form imitative of direct address. He then argues that poetry, conceived of as lexis, is a combination of two elements, one (melos) analogous to music, the other (opsis) to the plastic arts. The same concept may be expressed, Frye says, by translating lexis as “diction” when we are thinking of the musical element, and as “imagery” when we are thinking of it visually. Third, Frye maintains that each of the genres has a predominant rhythm. What he has done, then, in his discussion of epos, is to locate its rhythm in the principle of recurrence, defined as the quantitative relation between accent and meter.5 Since poetic meter is analogous to the metrics of music, Frye refines his definition of quantitative recurrence by using the principle of melos. The result, as we have seen, is the distinction between technical and sentimental forms of epos.

What remains is for Frye to discover the element of epos analogous to opsis. This he finds in imitative harmony or onomatopoeia. But since this technical device depends essentially on sound, it is not immediately obvious why Frye correlates it to opsis, rather than to melos where it would seem more naturally to belong. The explanation is that he does not use onomatopoeia in the strict sense of words which imitate sound; rather, he uses it to mean all of those combinations of words in which any correspondence between sound and sense results. Sometimes the sense produced by the sound is visual, in which case it is appropriate to speak of verbal opsis. At other times, however, as Frye’s illustrations indicate, onomatopoetic devices perform a different function, one that can be described as qualitative, like the suggestion of a mood. In these cases, no particular visual element need necessarily be present. Thus the analogy between imitative harmony and opsis loses some of its force, which may be one of the reasons why Frye himself speaks of the relations between epos and the pictorial arts as perhaps somewhat “farfetched” (AC, 258). That it does make sense, however, to speak of visual onomatopoeia can be illustrated by this passage:

The most remarkably sustained mastery of verbal opsis in English, perhaps, is exhibited in The Faerie Queene, which we have to read with a special kind of attention, an ability of catch visualization through sound. Thus inThe Eugh obedient to the bender’s will,the line has a number of weak syllables in the middle that makes {97} it sag out like a bow shape. When Una goes astray the rhythm goes astray with her:And Una wandring farre in woods and forrests. . . .(AC, 259–60)

Neither of Frye’s examples is strictly onomatopoetic in the sense that it employs words imitative of sounds. But in both lines the combination of sounds does reinforce the sense by creating an image; thus Frye’s use of the expression “verbal opsis.”

Imitative harmony, of course, is not restricted to epos. But Frye sees it as a continuous device in this genre, especially in the verse forms,6 whereas in drama, fiction, and lyric it appears only occasionally (AC, 261–62). “We have stressed imitative harmony,” he says, “because it illustrates the principle that while in Classical poetry sound-pattern or quantity, being an element of recurrence, is part of the melos of poetry, it is part of the opsis in ours” (AC, 262). The breadth of reference of the terms in this sentence results not only from the fact that a word like opsis is itself analogical, indicating a literary connection with the pictorial arts, but also from the fact that in the expression “imitative harmony” we have an analogy to opsis. In other words, onomatopoeia is analogous to verbal opsis, which is in turn analogous to the pictorial arts. This kind of argument illustrates Frye’s analogical method at its most complex level.

Although Frye seems to suffer some difficulty in making explicit the influence of opsis on his first genre, we should not let this obscure his main point: that in verse epos a complex of factors (stress, meter, quantitative sound patterns) produces a rhythm of recurrence. This is what distinguishes epos from the other genres, along with its different radical of presentation.7

Prose Fiction The radical of prose forms, Frye’s second genre, is the book or printed page. Together with epos, these forms, most notably prose fiction, constitute “the central area of literature” (AC, 250). Historically, however, the radicals of epos and fiction constitute a kind of dialectical tension: ” Epos and fiction first take the form of scripture and myth, then of traditional tales, then of narrative and didactic poetry, including the epic proper, and of oratorical prose, then of novels and other written forms” (AC, 250). Implicit here is the sequence of modes developed in the First Essay. As we move along this sequence, according to Frye, “fiction increasingly overshadows epos, and as it does, the mimesis of direct address changes to a mimesis of assertive writing. This in its turn, with the extremes of documentary or didactic prose, becomes actual assertion, and so passes out of literature” (AC, 250).

{98} Just as Frye uses the dialectic of assertion versus direct address to differentiate the mimetic forms of fiction and epos, so he establishes two other poles to account for their different rhythms. In every work of literature, “we can hear at least two distinct rhythms. One is the recurring rhythm. . . . The other is the semantic rhythm of sense, or what is usually felt to be the prose rhythm. . . . We have verse epos when the recurrent rhythm is the primary or organizing one, and prose when the semantic rhythm is primary” (AC, 263). Although prose rhythm is continuous, rather than recurrent, it does exhibit a number of metrical influences. These are especially apparent in pre-seventeenth-century prose forms, like euphuism. By the time of Dryden, however, prose has moved quite a distance from epos; hence its “distinctive rhythm . . . emerges more clearly” (AC, 265).

Frye characterizes this rhythm by pointing to the affinities between literary prose and, once again, melos and opsis. Among the signs of prose melos is the “tendency to long sentences made up of short phrases and coordinate clauses, to emphatic repetition combined with a driving linear rhythm, to invective, to exhaustive catalogues, and to expressing the process or movement of thought instead of the logical word order of achieved thought” (AC, 266). The opsis of prose, on the other hand, includes the “tendency to elaborate pictorial description and long decorative similes,” as well as the Jamesian “containing sentence” in which every element of syntax forms a pattern to be comprehended simultaneously (AC, 267).

Whether or not this last characteristic can legitimately be called a manifestation of rhythm depends, of course, on the definition of rhythm one starts with. Frye never explicitly defines rhythm. It is clear that his use of the word is not confined to its stricter sense of a sequence of approximately equal linguistic units. It is no less clear that he understands rhythm as something more than its etymological sense of a pleasing flow of sounds. Because Frye’s use of the term opsis (introduced to help define prose rhythm) is related to the static, imagistic, and conceptual aspects of literature, it appears to violate the conventional meanings of the word rhythm. In fact, in most of the instances where Frye uses opsis he is commenting not on rhythm in particular but on style in general.

As we have observed, Frye conceives of epos and fiction as constituting the center of literature. On one side lies drama, its radical of presentation being enactment, and its mimetic form, the external representation of sound and imagery. On the other side lies lyric, its radical being indirect address, or the poet talking to himself, so to speak; and since, as Frye says, the lyric poet “turns his back on his listeners,” its mimetic form is the internal representation of sound and imagery (AC, 249–50).

Drama {99} Frye’s treatment of the rhythm of drama is brief for two reasons. First, the melos and opsis of drama are obvious: actual music and spectacle. Second, although Frye labels the rhythm of drama “decorum,” the genre itself actually has no controlling rhythm (AC, 250). Consequently, even though he retains the term, his discussion remains largely a matter of style. The argument is this: Style is mainly a function of the writer’s distinctive voice (le style c’est l’homme); in drama this cannot be rendered directly since the writer must work through the dialogue of his characters; therefore, he has to adapt his own style to what his play demands. Such adaptation is decorum, or making the style appropriate to the content. “Decorum is in general,” Frye says, “the poet’s ethical voice, the modification of his own voice to the voice of a character or to the vocal tone demanded by subject or mood. And as style is at its purest in discursive prose, so decorum is obviously at its purest in drama, where the poet does not appear in person” (AC, 269). The rhythm of drama must finally be seen in terms of the rhythms of epos and prose. This is because drama tends to gravitate toward one or the other pole: dramatic epos or dramatic prose (AC, 269).

Frye claims that epos and fiction tend to manifest themselves respectively as myth and realism, but the correlation among the modes of the First Essay and the genres of the Fourth is even more explicit than this. “In the historical sequence of modes,” he says, “each genre in turn seems to rise to some degree of ascendancy” (AC, 270). Epos is more prominent in the mode of myth and romance; drama, in the high-mimetic mode of the Renaissance; fiction, other forms of prose, and verse, in the low-mimetic mode.8 We should expect, then, that Frye would seek to correlate the remaining genre—lyric—with the most recent forms in the historical sequence of modes, which is precisely what he does, saying that “it looks as though the lyric genre has some peculiarly close connection with the ironic mode and the literal level of meaning” (AC, 271).

Lyric The typical rhythm of lyric is “oracular, meditative, irregular, unpredictable, and essentially discontinuous, . . . emerging from the coincidences of the sound-pattern” (AC, 271). It differs from prose rhythm in being less conscious and deliberative. It differs from the rhythm of epos in being less habitual and less regularly metrical. And it differs from dramatic rhythm in not having to adapt to the demands of decorum. Frye labels the rhythm of lyric “association,” the reason being that the creative process for this genre is typically “an associative rhetorical process, most of it below the threshold of consciousness, a chaos of paronomasia, sound-links, ambiguous sense-links, and memory-links very like that of the dream” (AC, 271–72).

{100} Frye develops the relationship of the verbal pattern of lyric to music and spectacle with a host of analogues and illustrations. His method for further refining his definition of the rhythm of association is itself associative. The melos aspect of lyric is likened to cantillation—or to the fact that the words of poetry often yield themselves easily to the chant. The pictorial aspect, on the other hand, is associated with such things as typography and stanzaic arrangement at one extreme and visual imagery at the other (AC, 273-74).

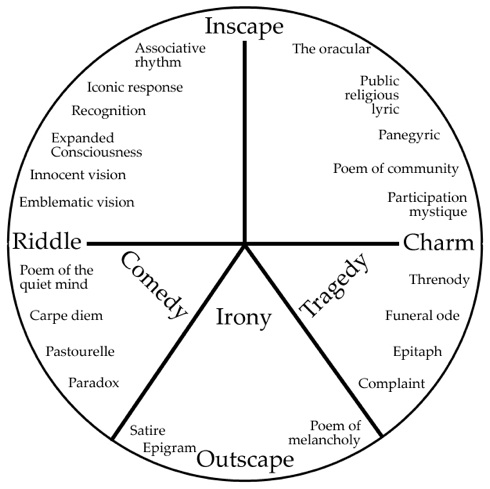

Frye also sees an analogy between lyrical melos and opsis and “two elements of subconscious association,” which he calls, “if the terms are thought dignified enough, babble and doodle” (AC, 275). Babble is the Urform which sound associations take in naive lyrics, like nursery rhymes and work songs, “where rhythm is a physical pulsation close to the dance, and is often filled up with nonsense words” (AC, 276). Incantation, uncontrolled physical response, magic, and pounding movement are several of the manifestations of babble. And since these elements can be characteristics of more sophisticated forms, Frye finds a more sophisticated term for this musical quality of the lyric. “The radical of melos,” he says, “is charm” (AC, 278). Doodle, on the other hand, is the unconscious Urform of verbal design, the kind of thing that might be “scribbled in notebooks to be used later; a first stanza may suddenly ‘come’ and then other stanzas of the same shape have to be designed to go with it, and all the ingenuity that Freud has traced in the dream has to be employed in putting words into patterns” (AC, 278). Frye later dignifies the lyrical doodle by relabeling it also: “The radical of opsis in-the lyric is riddle, which is characteristically a fusion of sensation and reflection, the use of an object of sense experience to stimulate a mental activity in connection with it.”9

Style

The different rhythms which make up Frye’s manual of style are in effect three, rather than four, drama possessing no rhythm peculiar to itself. These three rhythms taken together constitute what turns out to be a subtle theory of language, based on the expressive functions of prose, verse, and associative processes. Frye returns to the question of language and style in The Well-Tempered Critic, the second chapter of which is an attempt, as he says, “to reshape, in a slightly simpler form, some of the distinctions made in the fourth essay” of the Anatomy.10 If it is simpler, however, it is also more analytical, more technical, and in some respects more schematic than the first part of the Fourth Essay. Because of this, and because the reshaping helps both to clarify and to expand the earlier ideas, we need to look briefly at the later argument.

{101} Among Frye’s several aims in The Well-Tempered Critic is to reformulate the traditional notion of three levels of style by placing them into a more literary and less social frame of reference; to do this he posits the principle of “three primary verbal rhythms” distinguishable in ordinary speech. These are verse rhythm, dominated by “a regularly repeated pattern of accent or meter, often accompanied by other recurring features, like rhyme or alliteration”; prose rhythm, dominated by “the sentence with its subject-predicate relation”; and associative rhythm, dominated by the short, irregular phrase and by “primitive syntax” (WTC, 18–24, 55). Although these rhythms are said to characterize “ordinary speech,” it is obvious that they are similar to the rhythms of recurrence, continuity, and association—the categories Frye uses in the Anatomy to define, respectively, epos, fiction, and lyric. In The Well-Tempered Critic, however, the approach is somewhat different, for Frye sees the three kinds of rhythm as combining with each other in such a way as to produce six possible matrices: verse influenced by prose and associative rhythm; prose influenced by associative rhythm and verse; and associative rhythm influenced by verse and prose. Each of the primary rhythms, in other words, can be said to move in the direction of each of the other two. In the course of this movement, Frye is able to identify, in addition to the primary form of each rhythm, two additional stages: secondary or mixed forms, and tertiary or experimental ones. If prose, for example, with its continuous, syntactical, and expository rhythm, is taken as one primary form, it can be seen as passing through two isolable stages as it moves toward verse: rhetorical oratory and euphuism. Similarly, the influence of associative rhythm on normal prose can result in discontinuous aphorism (the secondary form) and oracular prose (the tertiary form). A little reflection shows that two types of rhythm for each matrix will yield twelve possible combinations, or, when the primary forms are added, fifteen categories altogether. In order for us to follow the course of Frye’s argument, I have represented this elaborate design graphically in Figures 16, 17, and 18.

Figure 16. Influence of prose and associative rhythm on verse. {p. 102} | ||

| Primary | Normal: the familiar territory of continuous verse, equidistant from prose and associative rhythm Example: Pope’s heroic couplets |

|

Forms Influenced by Prose |

Forms Influenced by Associative Rhythm |

|

| Secondary | Conversational (mixed): combination of iambic pentameter and semantic prose rhythm; absence of rhyme |

Lyric: more strongly influenced by associative rhythm than continuous verse; discontinuous features such as alliteration, patterns of repetition, complex verse rhyme, etc. |

Examples: blank verse of Milton, Keats, Tennyson, Browning, Wordworth | Example: The Faerie Queene | |

| Tertiary | Knittelvers (intentional doggerel): prose element in diction and syntax so strong that remaining features of verse appear as continuous parody; either disappearing or unobtrusive rhyme; tendency toward satire, discontinuity, and paradox | Echolalic: extreme use of rhetorical sound patterns (identical rhymes, intensified sound patterns); tendency toward discontinuity and verbal wit |

Examples: Donne’s “Fourth Satire,” Butler’s Hudibras, Byron’s Don Juan, Browning, Gilbert, Ogden Nash | Examples: poems of dream, reverie, and charm; parts of Spenser; Poe; Swinburne (“verbal blues and pensive jazz” together) | |

Figure 17. Influence of verse and prose on associative rhythm. {p. 102} | ||

| Primary | Normal: as a rhythm itself, subliterary. Simple patterns of repetition, as in communal chants, ballad refrains, nursery rhymes | |

Forms Influenced by Verse | Forms Influenced by Prose | |

| Secondary | Free verse: series of phrases, with no fixed metrical pattern, rhythmically separated; tendency toward the catalogue | “Free Prose”: associative rhythm influenced, but not organized, by the sentence; the associative monologue; congenial to prose satire; uninhibited punctuation |

Examples: Ossian, Whitman | Examples: personal letters, diaries (e.g., Samuel Sewall’s), Swift’s Journal to Stella, Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, Sterne’s Tristram Shandy | |

| Tertiary | Imagistic: associative writing as close to verse as possible without becoming verse; catalogue poetry; hypnotic chant based on devices of repetition | Stream-of-consciousness: the mingling of associative and prose rhythms in extreme form; echolalia; repetition of sound and thematic words |

Examples: Amy Lowell’s imagism, John Gould Fletcher’s “color symphonies” | Examples: Joyce; certain forms of prayer, as in Donne’s Meditations | |

Figure 18. Influence of verse and associative rhythm on prose. {p. 103} | ||

| Primary | Normal: the language of exposition and description; consistent with sentence rhythm; features of associative rhythm are purely “accidental”; continuous forms Example: Darwin’s Origin of the Species | |

Forms Influenced by Verse | Forms Influenced by Associative Rhythm | |

| Secondary | Rhetorical (oratorical): expository language, but with unmistakable metrical qualities, deliberately employed; meditative element appeals to imagination or emtions | Discontinuous (aphoristic): tone of ordinary conversation; easy use of parenthesis, unforced repetition of certain words and ideas; produces clichès, accepted ideas, proverbs, epigrams, and parodies of these |

Examples: Gibbon’s Decline and Fall, Churchill’s 1940 speeches, Gettysburg Address, Johnson’s letter to Chesterfield, Browne’s Urn Burial, Taylor’s Holy Dying | Examples: Shaw’s prose, Blake’s proverbs, philosophical sententiae, proverbial religious wisdom | |

| Tertiary | Euphuistic: ornamenting of prose rhythm by rhetorical devices of verse (rhyme, alliteration, assonance, metrical balance, etc.); discontinuous and paradoxical | Oracular: rhythmically based prose with elusive and paradoxical qualities; extreme forms tend toward parody by aiming to break through entire process of verbal articulation |

Examples: Greene’s Card of Fancy; Lyly; Thomas’s Under Milk Wood | Examples: Rimbaud’s Season in Hell, Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra, Renè Char, St. John Perse, Paul Fort | |

A study of the interlocking classes of these charts (which represent but a small part of Frye’s brilliantly conceived lectures) will reveal the way in which the various literary styles in particular derive ultimately from the rhythms of language in general. It is this part of his argument which shows an especially close parallel to the Fourth Essay of the Anatomy. As in all our attempts, however, to represent Frye’s thought schematically, these diagrams suggest a sharper disjunction between stylistic forms than he would want ultimately to make. He does not intend to develop a mechanical means for fitting any work into its appropriate slot without remainder. Rather, the fifteen categories should be seen as relative positions on a sliding scale of stylistic rhythms.11

{103} Having distinguished the primary rhythms of ordinary speech and shown how they influence and interact with each other, Frye turns back to the question of three levels of style, seeking to relate the traditional division of low, middle, and high styles not merely to verbal rhythms themselves but to kinds of poetic diction as well. This part of The Well-Tempered Critic represents an extension of the ideas developed in Anatomy of Criticism. It is based on another set of dialectical pairs, two tendencies in literature which Frye calls the hieratic and the demotic:

The hieratic tendency seeks out formal elaborations of verse and prose. The hieratic poet finds, with Valery, that the kind of poetry he wants to write depends, like chess, on complex and arbitrary rules, and he experiments with patterns of rhythm, rhyme and assonance, as well as with mythological and other forms of specifically poetic imagery. The demotic tendency is to minimize the difference between literature and speech, to seek out the associative or prose rhythms that are used in speech and reproduce them in literature. (WTC, 94)

This pair of terms, together with the three rhetorical levels, produces yet another matrix of classes: high, middle, and low hieratic; high, middle, and low demotic. It is convenient to represent this framework by means of a chart also (Figure 19). As is the case with all of Frye’s {104} schemata, however, more is required to define a given class than simply a combination of the categories on his vertical and horizontal axes.

| Demotic | Hieratic | |

|---|---|---|

Figure 19. Levels of style. {p. 104} | ||

| Low | Literary use of colloquial and familiar speech (the theoretical view expressed in Coleridge’s criticism of Wordsworth’s Preface) | Words in process; language which bypasses conventionally articulate communication; influenced by associative rhythm; the area of creative association which suspends conventional rules |

Examples: the vulgar idiom in fictional and dramatic dialogue; colloquialisms used to provide lower tone, as in Whitman; intentional doggerel as in Hudibras and Sweeney Agonistes; neurotic, compulsive babble of the ego, as in Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground and in Beckett | Examples: deliberate wit; experimental, tertiary forms (euphuism, echolalia); free verse and “free prose”; Sterne; Smart’s Jubilate Agno; Finnegans Wake | |

| Middle | Ordinary language of communication, at once plain and cultivated | Formal language of poetic expression; what Hopkins calls “Parnassian” style; literature as art of conventional communication |

Examples: expository prose and narrative; didactic verse | Examples: deliberately rhetorical prose, as in Gibbon; the formulaic epic | |

| High | Sententious and aphoristic use of language; deals with the traditional and familiar, elevated to the level of sublime; essentially discontinuous; the social apotheosis of proverb | Language used to express the intense momentary vision or the epiphany; individual rather than social vision |

Examples: sacred writings throughout; literary forms of religious revelation | Examples: the discontinuous, oracular lyric, as in Eliot, Pound, Rilke, Valèry; lyrical portions of Vita Nuova (Dante) and The Dark Night of the Soul (St. John of the Cross) | |

This can be illustrated by observing the kinds of criteria Frye uses to define, say, the high demotic and hieratic styles. The high demotic style is “essentially aphoristic” and sententious; it deals “with the traditional and familiar,” elevated to the level of the sublime; it manifests itself chiefly in discontinuous forms; it represents the social apotheosis of the proverb (WTC, 101–3). The hieratic style, on the other hand, is, at its highest level, more a matter of intensity than sublimity; it is language used to express the momentary vision, or epiphany; it manifests itself in the discontinuous, oracular lyric (WTC, 103–4). These principles are similar to those Frye has used to distinguish the rhythmical forms (Figures 16–18), but with this difference: his categories now are much more a function of the reader’s response, recognition, and acceptance. The high demotic style deals, Frye says,

with those moments of response to what we feel most deeply in ourselves, whether love, loyalty or reverence. . . . Such points of concentration do not differ in kind from middle or low style, and hence do not violate the context from which they emerge. They are of relatively short duration, as they do not depend on {105} sequence or connection. What they do depend on is the active participation of the reader or hearer: they are points which the reader recognizes as appropriate for the focusing of his own consciousness. (WTC, 102)

This passage, seen in relation to Frye’s disjunction between knowledge and experience, is clearly on the experiential side and thus moves away from those kinds of norms which, more often than not, he seeks to establish. The question of style, therefore, at its “highest” levels at least, is partially a matter of subjective intuition, not unlike the Arnoldian “touchstones.”12

The context of subjective response provides the occasion for Frye to move out into an even broader series of contexts.

Our present argument seems to indicate the existence of two kinds of “high” literary experience, . . . one in general verbal practice and one more strictly confined to literature; one a recognition of something like verbal truth and the other a recognition of something like verbal beauty. High style in demotic writing depends largely on social acceptance: it is the apotheosis of the proverb, the axioms that a society takes to its business and bosom. Hieratic writing is more dependent on canons of taste and esthetic judgment, admittedly more flexible and more elusive than counsels of behavior. (WTC, 105–6)

Acceptance and taste, truth and beauty—these criteria form one of the contexts for determining high style and must therefore be set beside the other, less expansive norms (rhythm, form, diction, etc.) that Frye employs to classify the literary uses of language.

We observed at the beginning of this chapter that both aspects of Frye’s rhetorical criticism—the stylistic and the generic—call for a social response. His theory of rhythm and, as an extension, his theory of style illustrate this well, for his argument gradually expands from a concern with particular and more or less objectively identifiable elements of style, like poetic meter, to a concern with the broader stylistic contexts, defined in relation to community acceptance and social taste. When he defines high style as the “recognition of truth and beauty in verbal form” (WTC, 108), we can see more clearly the place of rhetoric in the triadic framework outlined at the beginning of the Fourth Essay. The theories of rhythm and style, however, form but half of Frye’s theory of rhetoric, and we must turn now to examine his taxonomy of specific forms.

Generic Forms

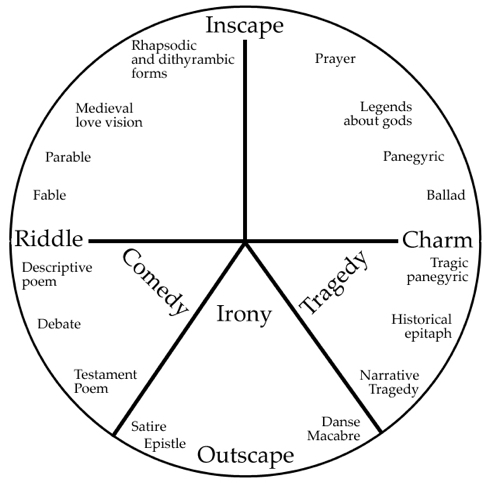

Anatomy of Criticism dissects not simply the obvious features of the body of literature but the obscure ones as well. Nowhere is this more evident {106} than in the last half of the theory of genres, where we discover such specific forms as auto, symposium, archetypal masque, and even one called “anatomy” itself. Frye’s use of the word “specific” should not be understood to mean that he is proposing neatly to classify all the species of a given genre (e.g., drama). His “specific forms” approximate only roughly what are commonly thought of as literary species (e.g., tragic drama). Several of the fundamental assumptions we have encountered thus far appear also in this section. The dichotomy between fictional and thematic, which made its first appearance in the theory of modes, reappears here as one of the organizing principles of Frye’s discussion, illustrating, incidentally, that the Anatomy has something of a cyclic design itself, the categories of the Fourth Essay turning back to those of the First. Fictional and thematic serve to separate the four genres into two distinct groups. Under the first category Frye locates drama and prose fiction; and under the second, epos and lyric. Prose forms which are more thematic than fictional, like oratorical prose, and verse forms which are more fictional than thematic, like the purely narrative poem, take their respective places in the dichotomy (AC, 243). Since the genres tend toward one or the other of the modal categories, we can expect to find the cyclical paradigm at work here also. Other important principles recurring throughout Frye’s treatment of the specific forms are the innocence-experience dichotomy, the conception of art as lying midway between history (event) and philosophy (idea), and the analogy of literature to melos and opsis which we have examined above. These principles guide Frye’s discussion of the specific forms.

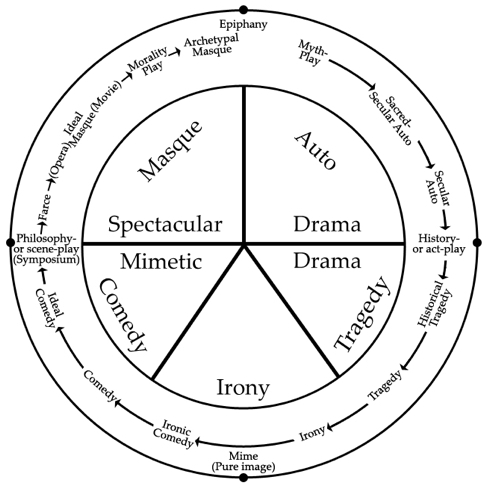

Specific Forms of Drama The traditional division of drama into tragedies and comedies is, according to Frye, “a conception based entirely on verbal drama, and does not include or account for types of drama, such as the opera or masque, in which music and scenery have a more organic place” (AC, 282). He attempts to modify the traditional view by means of yet another elaborate paradigm, this one a combination of his familiar cyclical and dialectical models. The first dialectical principle underlying his argument is the division of dramatic kinds into two large categories, spectacular and mimetic. A related pair of categories, epiphany (or pure vision) and mime (or pure image), constitutes what might be conceived of as the extreme dramatic points of an imaginary vertical axis. At the horizontal poles of this figure lie two other dramatic forms, what Frye calls the “history-play” (or act-play) with its emphasis on pure event and the “philosophy-play” (scene-play or symposium) with its emphasis on pure idea. Now if we were to connect these points with four arcs we approximate the kind of circular model Frye has in mind, around the perimeter of which he locates the various {107} specific forms. Figure 20 represents a simplified version of this diagram. A glance at the figure will indicate the central defining role which such dialectical pairs as event and idea, and myth and irony assume in the overall design.

Figure 20. Specific forms of drama. {p. 107} |

|

The upper-right-hand quadrant of the diagram represents what Frye provisionally calls the “myth-play,” later relabeled the auto (the name is taken from Calderon’s Autos Sacramentales) because of the ambiguities attendant on the word “myth.” His method of defining this form is a complex one, drawing as it does upon a number of criteria. In the first place, the auto is spectacular drama, which means that music and scenery have just as organic a role in determining its form as {108} language itself: its material cause is not exclusively verbal. Frye sees a number of variations on the basic form. In its most restricted sense auto means “a form of drama in which the main subject is sacred or sacrosanct legend, such as miracle plays, solemn and processional in form but not strictly tragic” (AC, 365). Using this definition as a starting point, he outlines, in a kind of quasi-historical way, the movement from pure or sacred auto to forms which are at once sacred and secular (e.g., the Japanese No drama) and then to forms in which the sacred element is completely displaced. This latter would be a purely secular auto, or what could also be called, as Frye’s examples indicate, a heroic romance (e.g., Marlowe’s Tamburlaine). Other examples of the auto include Aeschylus’ The Suppliants, its “predominantly musical structure” comparable to the modern oratorio, and Wagner’s operas, which expand “the heroic form all the way back to the sacramental drama of the gods” (AC, 283). Throughout Frye’s discussion of the auto he relies not only on concepts related to the means of imitation (spectacular) and the dramatic subject (either pure or displaced sacred legend) but also upon such criteria as the characteristic mood and resolution, the symbolic emphasis, the type of hero, the source of the dramatic catastrophe, and the kind of audience appeal. Here, for example, are some excerpts from the discussion of pure or sacred auto: “The characteristic mood and resolution of the myth-play are pensive. . . . The myth-play emphasizes dramatically the symbol of spiritual and corporeal communion. . . . The appeal of the myth-play is a curious mixture of the popular and esoteric” (AC, 282). The method of definition, in short, is not a simple one, relying upon at least a half-dozen important distinctions.

The same is true of Frye’s discussion of those forms which occupy the other quadrant of his “spectacular” semicircle and to which he attaches the label “masque.” (We pass over his treatment of dramatic tragedy, irony, and comedy, where the method consists chiefly of placing distinctions we have previously encountered—in the theory of modes and the theory of mythoi—into a dramatic context.) When Frye comes to the fourth quadrant, having concluded his discussion of comic dramatic forms, he remarks: “We are strongly tempted to call our fourth area ‘miscellaneous’ and let it go; but it is precisely here that new generic criticism is needed” (AC, 287). Thus he devotes more space to analyzing the various forms of the masque than to all of the other dramatic forms combined.

The masque, according to the definition of Frye’s glossary, is “a species of drama in which music and spectacle play an important role and in which the characters tend to be or become aspects of human personality rather than independent characters” (AC, 366). Spectacular drama, with its emphasis on both melos and opsis, is, so to speak, the {109} genus of both masque and auto. The two forms, however, are similar in one other respect: the structure of both is not parabolic, as in mimetic drama, but linear. In other words, whereas typical five-act tragedies and comedies work toward an end which illuminates the beginning, spectacular drama “is by nature processional, and tends to episodic and piecemeal discovery, as we can see in all forms of pure spectacle, from the circus parade to the revue” (AC, 289). Thus what differentiates masque and auto from mimetic drama is both their spectacular basis and their processional structure. On the other hand, what distinguishes masque from auto as separate species of spectacular drama is a question best approached by considering Frye’s elaboration of the major subspecies within the former category.

He conceives of these subspecies as located on a continuum, running from the ideal masque at one end to the archetypal masque at the other. The difference between these two extremes is largely a matter of the different conceptions of the audience they assume. The ideal masque, Frye says, is “usually a compliment to the audience, or an important member of it, and leads up to an idealization of the society represented by that audience” (AC, 287), whereas the archetypal masque “tends to individualize its audience by pointing to the central member of it” (AC, 290). The conception of the audience, moreover, is one of the things which distinguishes masque from both the auto and the mimetic forms. “The essential feature of the ideal masque,” Frye says,

is the exaltation of the audience, who form the goal of its procession. In the auto, drama is at its most objective; the audience’s part is to accept the story without judgment. In tragedy, there is judgment, but the source of the tragic discovery is on the other side of the stage; and whatever it is, it is stronger than the audience. In the ironic play, audience and drama confront each other directly; in the comedy the source of the discovery has moved across to the audience itself. The ideal masque places the audience in a position of superiority to discovery. The verbal action of Figaro is comic and that of Don Giovanni tragic; but in both cases the audience is exalted by the music above the reach of tragedy and comedy, and, though as profoundly moved as ever, is not emotionally involved with the discovery of plot or characters. It looks at the downfall of Don Juan as spectacular entertainment. (AC, 289)

There are yet other important criteria in Frye’s definition of the ideal masque. It draws, he says, upon “fairly stock” narratives and characters (AC, 287), its emphasis is on the ideal, its settings are Arcadian—{110} characteristics which explain its proximate relation to comedy as well as suggesting one of the reasons for the audience’s exaltation. As drama moves away from comedy and toward the apex of Frye’s cycle, it enters the area of the archetypal masque, a species which not only individualizes its audience, as we have seen, but becomes more serious in the process. Like all forms of spectacular drama its settings are detached from time and space, “but instead of the Arcadias of ideal masque, we find ourselves frequently in a sinister limbo, like the threshold of death in Everyman, the sealed underworld crypts of Maeterlinck, or the nightmares of the future in expressionist plays” (AC, 290). The archetypal masque, in short, is the prevailing species we encounter in most contemporary “highbrow drama,” especially European forms, and in “experimental operas and unpopular movies” (AC, 290). The word “archetypal” here is explicitly Jungian and has little relation to its ordinary meaning for Frye as the conventional, recurring symbol. We should remember that in his definition of the masque proper, ethos means “aspects of personality rather than independent characters.” In the ideal masque, ethos becomes the stock or type character. I n the archetypal masque, with its sinister setting, it becomes the “interior of the human mind” as characterization breaks down “into elements and fragments of personality” (AC, 291); thus the appropriateness of the Jungian terminology. “This is why,” Frye says, “I call the form the archetypal masque, the word archetype being in this context used in Jung’s sense of an aspect of the personality capable of dramatic projection. Jung’s persona and anima and counsellor and shadow throw a great deal of light on the characterization of modern allegorical, psychic, and expressionist dramas, with their circus barkers and wraith-like females and inscrutable sages and obsessed demons” (AC, 291).

The ideal and archetypal forms of the masque are but two of the many species that Frye locates along the arc of his fourth quadrant. The opera, or “musically organized drama,” flanks the masque on one side; and the movie, or “scenically organized drama,” on the other. Other dramatic species with affinities toward one or the other, or both, of these forms are puppet plays, Chinese romances, commedia dell’arte, ballet, and pantomime (AC, 288). Two other forms that Frye mentions are farce and morality plays: the former lies close to the ideal masque, and the latter, with their type characters representing good and evil in open conflict, approach the area of the archetypal masque (AC, 290). Finally, at the extreme right of the archetypal masque, which brings us to the beginning of the auto, we reach the point of the epiphany, “the dramatic apocalypse or separation of the divine and the demonic, a point directly opposite the mime, which presents the simply human mixture” (AC. 2921. This is the area Nietzsche had in mind {111} when he spoke of the birth of tragedy as the Dionysian revel of satyrs being brought into line with the mandates of an Apollonian god (AC, 292), the two opposites representing in a general way Frye’s own masque and auto.

Standing back from Frye’s treatment of the specific forms of drama, we observe, by way of summary, that he begins his argument at the level of Aristotle’s efficient cause: the manner of imitation, or in Frye’s own terms, “the radical of presentation.” This permits him to distinguish drama—those works enacted by hypothetical characters—from the other genres. He then moves to the level of what Aristotle would call the material cause, the means of imitation. His assumption at this point is that a concentration on the lexis of drama cannot properly account for those species in which melos and opsis play an important, if not a dominant role. Thus, to provide a more synoptic view, Frye uses the concept “spectacular” to describe those forms where music, dance, and scenic or sensational means are directed toward an end that ordinarily excludes the dramatic tensions peculiar to the parabolic structure of comedy and tragedy. His division between spectacular and mimetic (or verbal) drama, therefore, is chiefly a distinction based on the different means of imitation. At this point our Aristotelian parallel breaks down; for when Frye comes to differentiate auto from masque or to distinguish among the various subtypes of a given species, he relies on a wide variety of criteria: mood, resolution, theme, character, setting, symbolic emphasis, nature of the audience—all of these plus a host of specific works used as illustrations. It would be possible to draw a general analogy between some of these principles and Aristotle’s formal and final causes, since Frye does speak at times about what is being represented and the peculiar effect the representation achieves; but this would be to distort his argument since these principles are not employed consciously or consistently. More to the point is the fact that the kinds of criteria Frye uses, once he has passed beyond the spectacular-mimetic distinction, are the same as those employed to distinguish the mythoi in his theory of archetypes. This is why his survey of the specific forms is more an analysis of the kinds of dramatic fictions than a neat classification of dramatic species.13 This is especially true of the subtypes where, for example, ideal comedy and ideal masque, or archetypal masque and morality play tend to merge almost indistinguishably into one another. The differentiating criteria, however, do provide for a synoptic account of significant variations within the genre of drama, which is Frye’s aim; and the entire effort must be judged as a meaningful expansion of the traditional perspective. A somewhat different set of criteria, however, underlies Frye’s analysis of the specific forms of prose fiction, a topic to which we now turn.

Specific Continuous Forms: Prose Fiction {112} Frye’s treatment of prose fiction, if not one of the most influential aspects of his theory, is at least one of the best-known and most frequently anthologized parts of the Anatomy.14 By the expression “continuous forms” Frye means those literary works in which the predominant rhythm is that of semantic continuity. He includes “prose fiction” in the title of this section for the obvious reason that there are some continuous forms which are neither prose nor fiction: thematic epics, didactic poetry and prose, compilations of myth—any form, in short, where the poet “communicates as a professional man with a social function” (AC, 55). This quotation comes from the First Essay where Frye makes the distinction between episodic and encyclopaedic works, arguing that the latter are continuous in the sense of forming more extended patterns. Therefore “continuous,” as it applies to prose fiction in the Fourth Essay, refers not only to the continuity of semantic rhythm but also to the relative length of the fictional work. The organization of this section derives from a distinction among four major types of prose fiction, represented in Figure 21. The two pairs of categories here are based upon different principles. “Personal” refers to ethos or characterization and “intellectualized” to dianoia or content, whereas the extroverted-introverted dichotomy is essentially a matter of rhetorical technique, the latter terms describing whether a writer’s manner of representation tends more toward objectivity or subjectivity. These are not the only categories, however, which Frye uses to define his fictional forms. The bulk of his argument consists of drawing certain distinctions between the two forms of “personal” fiction (novel and romance) and between the two “intellectualized” forms (confession and anatomy).

| extroverted | introverted | |

|---|---|---|

Figure 21. Specific continuous forms of prose fiction. {p. 112} | ||

| ETHOS: personal | Novel | Romance |

| DIANOIA: intellectualized | Anatomy | Confession |

The essential difference between novel and romance,” says Frye, “lies in the conception of characterization” (AC, 304). He illustrates this by setting down a series of opposing qualities which are said respectively to characterize the two forms:

{113} The romancer does not attempt to create “real people” so much as stylized figures which expand into psychological archetypes. It is in the romance that we find Jung’s libido, anima, and shadow reflected in the hero, heroine, and villain respectively. That is why romance so often radiates a glow of subjective intensity that the novel lacks, and why a suggestion of allegory is constantly creeping in around its fringes. Certain elements of character are released in the romance which make it naturally a more revolutionary form than the novel. The novelist deals with personality, with characters wearing their personae or social masks. He needs the framework of a stable society, and many of our best novelists have been conventional to the verge of fussiness. The romancer deals with individuality, with characters in vacuo idealized by revery, and, however conservative he may be, something nihilistic and untamable is likely to keep breaking out of his pages. (AC, 304–5)

The ultimate reference for each pair of terms in this dialectic of opposites is ethos. In other words, determining whether a work of prose fiction is realistic or allegorical, conservative or revolutionary, stable or untamable, calm or intense, social or individual, and thus whether it is a novel or a romance, requires that our attention be focused essentially not upon mythos or dianoia but upon characterization. I say “essentially” because there are other, although less important, considerations. Frye observes, for example, that the plot and dialogue of the novel have an affinity with the conventions of the comedy of manners, whereas the conventions of romance are linked more closely with the tale and the ballad (AC, 304). Moreover, Frye outlines a difference in the approaches of the novelist and the romancer to historical material. The novelist, dealing creatively with history, “usually prefers his material in a plastic, or roughly contemporary state, and feels cramped by a fixed historical pattern” (AC, 306). In the romance, on the other hand, the historical pattern is usually less fluid and contemporary, most romances being set in the past. Frye sees some relation between this last tendency and his theory of modes: the romance as a mode lying between myth and realism is obviously, in the sequence outlined in the First Essay, further removed chronologically from the mimetic and ironic tendencies appropriate to the novel. It is no accident, Frye observes, that “most” ‘historical novels’ are romances” (AC, 307).

As a concept for defining the confession and the anatomy, ethos plays a secondary role. The confession, a specialized form of autobiography, presents a writer’s life in such a way as “to build up an integrated pattern” (AC, 307). But even though the subject is {114} ostensibly the author himself, “some theoretical or intellectual interest” nearly always plays a dominant role. This is what distinguishes the confession from the novel proper, where the theoretical interest is always subordinated to the technical problem of “personal relationships” (AC, 308). The anatomy is also an “intellectualized” form, similar to the confession in its ability to represent theoretical statements and abstract ideas. It differs in being one step further removed from a concern with ethos. Its characters are more stylized than realistic, not so important in themselves as in the mental attitudes they express. In Frye’s words, the anatomy “presents people as mouthpieces of the ideas they represent” (AC, 309). It is a “loose-jointed narrative form” (AC, 309), embracing a wide variety of subtypes which range from pure fantasy at one extreme to pure morality at the other. It differs from the romance in that it “is not primarily concerned with the exploits of heroes, but relies on the free play of intellectual fancy and the kind of humorous observation that produces caricature” (AC, 309–10); thus the tendency of the anatomy toward various kinds of satire.

Once Frye has distinguished the four types, he is quick to note that very few exist in “pure” form. “There is hardly any modern romance,” he says, “that could not be made out to be a novel, and vice versa. The forms of prose fiction are mixed, like racial strains in human beings, not separable like the sexes” (AC, 305). Similarly, we find Frye making such statements as these: the confession “merges with the novel by a series of insensible gradations”; or, “the anatomy, of course, eventually begins to merge with the novel, producing various hybrids” (AC, 307, 312). Thus Frye’s specific forms are more like “strands,” to use his own word, combined in various ways in a given work of prose fiction.

Despite the fact that the four principal strands cannot, on the whole, be found as pure species, Frye nonetheless gives a number of examples of the kinds of works and writers he would place in each category. Some of these, including typical “short” forms, are represented in the following outline, which also lists his examples for the eleven possible combinations among the four categories.

1. | Novel | |

Fielding, Tom Jones | Jane Austen’s works | |

Dickens, Little Dorrit | Defoe | |

Butler, The Way of All Flesh | James | |

Huxley, Point Counterpoint | ||

Short form: Short stories (e.g., Chekhov, Mansfield) | ||

{115} 2. | Romance | |

Bronte, Wuthering Heights | William Morris | |

Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress | Hawthorne | |

Maturin, Melmoth the Wanderer | Scott | |

Short form: Poe’s tales; Boccaccio, Decameron | ||

3. | Confession | |

Augustine, Confessions | Bunyan, Grace Abounding | |

Rousseau, Confessions | Newman, Apologia | |

Browne, Religio Medici | Hogg, Confessions of a Justified Sinner | |

Short form: the familiar essay; Montaigne’s livre de bonne foy | ||

4. | Anatomy | |

Athenaeus, Deipnosophists | Kingsley, Water Babies | |

Macrobius, Saturnalia | Carroll, Alice in Wonderland | |

Southey, The Doctor | Amory, John Buncle | |

Burton, Anatomy of Melancholy | Voltaire, Candide | |

Landor, Imaginary Conversations | Walton, The Compleat Angler | |

Flaubert, Bouvard et Pecuchet | Wilson, et al., Noctes Ambrosianae | |

Butler, Erewhon; Erewhon Revisited | Boethius, Consolation of Philosophy | |

Huxley, Brave New World | Swift, Gulliver’s Travels | |

Petronius, Lucian, Varro, Rabelais, Erasmus, Peacock | ||

Short form: dialogue or colloquy, as in Erasmus, Voltaire; cena or symposium | ||

5. | Novel-Romance | |

George Eliot’s early novels | Austen, Northanger Abbey | |

Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter | Flaubert, Madame Bovary | |

Conrad, Lord Jim | ||

6. | Novel-Confession | |

Defoe, Moll Flanders | Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man | |

7. | Novel-Anatomy | |

Sterne, Tristram Shandy | George Eliot’s later novels | |

Proletarian novels of the 1930s | ||

8. | Romance-Confession | |

De Quincey, Confessions of an English Opium Eater | Borrow, Lavengro and The Romany Rye | |

9. | Romance-Anatomy | |

Melville, Moby Dick | Rabelais | |

10. | {116} Confession-Anatomy | |

Carlyle, Sartor Resartus | Kierkegaard, Either-Or | |

11. | Novel-Romance-Confession | |

Richardson, Pamela | ||

12. | Novel-Romance-Anatomy | |

Cervantes, Don Quixote | ||

13. | Novel-Confession-Anatomy | |

Proust | ||

14. | Romance-Confession-Anatomy | |

Apuleius | ||

15. | Novel-Romance-Confession-Anatomy | |

Joyce, Ulysses | ||

All of this is highly schematic. Frye makes it that way deliberately, for he wants first to analyze the forms of prose fiction (the first four categories) and then synthesize them (the last eleven) “in order to suggest the advantage of having a simple and logical explanation for the form of, say, Moby Dick or Tristram Shandy” (AC, 313). Whether or not Frye’s approach is in fact simple and logical is perhaps a matter for debate, though the issue cannot be decided except in terms of the criteria he himself has chosen for his distinctions. The more significant point seems to be that Frye is offering an “explanation” for the specific forms, not a taxonomy for its own sake.

The claims that Frye makes for generic criticism of the variety just outlined are more directly stated in this section than in the one on drama. He himself asks what function is served by the distinction, say, between novel and romance, especially when, as he has argued, there are few “pure” forms of either. His answer is that a writer “should be examined in terms of the conventions he chose” (AC, 305), an answer directed especially toward the novel-centered view of prose fiction. Frye makes this point several times; perhaps it is best expressed in the following passage:

William Morris should not be left on the side lines of prose fiction merely because the critic has not learned to take the romance form seriously. Nor, in view of what has been said about the revolutionary nature of the romance, should his choice of that form be regarded as an “escape” from his social attitude. If Scott has any claims to be a romancer, it is not good criticism to deal only with his defects as a novelist. The romantic qualities of The Pilgrim’s Progress, too, its archetypal characterization and its {117} revolutionary approach to religious experience, make it a well-rounded example of a literary form: it is not merely a book swallowed by English literature to get some religious bulk in its diet. Finally, when Hawthorne, in the preface to The House of the Seven Gables, insists that his story be read as romance and not as novel, it is possible that he meant what he said, even though he indicates that the prestige of the rival form has induced the romancer to apologize for not using it. (AC, 305–6)

The plea here, in part, is for a less provincial attitude, for an ecumenical perspective which does not relegate some forms of prose, like the confession, to that “vague limbo of books which are not quite literature because they are ‘thought,’ and not quite religion or philosophy because they are Examples of Prose Style” (AC, 307).

Frye believes that critics have been especially remiss in not taking account of the anatomy. Although this tradition contains a rather curious assortment of works, he attempts to show that it is more than simply a miscellaneous catch-all for types of prose which the other categories do not adequately describe. It is difficult not to conclude, given the criteria of Frye’s discussion, that his “anatomy” is any less unified and conventional a form than the other three. Recognizing that it does appear both as a pure form (Boethius’ Consolation, Burton’s Anatomy, Walton’s Compleat Angler) and in combination with other forms should, Frye argues, “make a good many elements in the history of literature come into focus” (AC, 312). Philip Stevick, for one, has shown the anatomy to be a useful distinction.15

Frye almost invites us to consider the similarity between the anatomy as a prose form and his own Anatomy, some of the phrases he uses to describe the former are, mutatis mutandis, apt characterizations of his own work. Consider, for example, the following: The anatomy “relies on the free play of intellectual fancy.” It “presents us with a vision of the world in terms of a single intellectual pattern” (AC, 310). “The word ‘anatomy’ in Burton’s title [Anatomy of Melancholy] means a dissection or analysis, and expresses very well the intellectualized approach of this form” (AC, 311). And finally, the anatomist, “dealing with intellectual themes and attitudes, shows his exuberance in intellectual ways, piling up an enormous mass of erudition about his theme” (AC, 311). If the analogy is intentional on Frye’s part, and it seems to be, his own title is not without that touch of wit which appears everywhere in his work. More importantly, however, the title calls attention to and reinforces what many of Frye’s readers have felt about the creative nature of his achievement. We will examine this aspect of his work in chapter 7.