Northrop Frye & Critical Method

Robert D. Denham

Chapter 2: Theory of Symbols

Chapter Sections:

Ethical Criticism: The Contexts of Literary Symbols

The Taxonomy of Symbolism

The Blakean Influence

The Phases of Symbolism Synthesized

Ethical Criticism: The Contexts of Literary Symbols

In Part I of The Critical Path, where Frye gives an account of his own intellectual history in moving from the study of Blake to writing Anatomy of Criticism, he remarks that his theory of literature was developed from an attempt to answer two questions: What is the total subject of study of which criticism forms a part, and how do we arrive at poetic meaning? (CP, 14–15). The Second Essay, “Ethical Criticism: Theory of Symbols,” addresses itself to the latter question. Frye’s starting point is to admit the principle of “polysemous” meaning, a version of Dante’s fourfold system of interpretation. This principle can be called an “established fact,” he says, because of the “simultaneous development of several different schools of modern criticism, each making a distinctive choice of symbols in its analysis” (AC, 72). Once the principle is granted, there are two alternatives: “We can either stop with a purely relative and pluralistic position, or we can go on to consider the possibility that there is a finite number of valid critical methods, and that they can all be contained in a single theory.”1

Frye develops his argument by first placing the issue of meaning in a broader context:

The meaning of a literary work forms a part of a larger whole. In the previous essay we saw that meaning or dianoia was one of three elements, the other two being mythos or narrative and ethos or characterization. It is better to think, therefore, not simply of a sequence of meanings, but of a sequence of contexts or relationships in which the whole work of literary art can be placed, each context having its characteristic mythos and ethos as well as its dianoia or meaning. (AC, 73)

Context, then, rather than meaning becomes the organizing principle; and the term Frye uses for the contextual relationships of literature is “phases,” which becomes the organizing category for the taxonomy of the Second Essay.

{32} The word “ethical” in the title of this essay obviously does not derive from the meanings which ethos had in the First Essay: Frye does not intend to expand the analysis of characterization found there. Nor is he concerned with something else “ethical” might imply, judicial evaluations or the moral element of literature. The word refers rather to the connection between art and life which makes literature a liberal yet disinterested ethical instrument. Ethical criticism, Frye says in the Polemical Introduction, refers to a “consciousness of the presence of society. . . . [It] deals with art as a communication from the past to the present, and is based on the conception of the total and simultaneous possession of past culture” (AC, 24). It is the archetype, as we shall see in chapter 3, which provides the connection between the past and the present. Unlike the other essays in the Anatomy, Frye’s theory of symbols is directed toward an analysis of criticism. “Phases” are contexts within which literature has been and can be interpreted: they are primarily, though not exclusively, meant to describe critical procedures rather than literary types, which is to say that the phases represent methods of analyzing symbolic meaning. Frye’s aim is to discover the various levels of symbolic meaning and to combine them into a comprehensive theory.

“Symbol” is the first of three basic categories Frye uses to differentiate the five phases. Here we encounter once again the breadth of reference and unconventional usage which many of Frye’s terms have, for in the Second Essay symbol is used to mean “any unit of any literary structure that can be isolated for critical attention” (AC, 71). This includes everything from the letters a writer uses to spell his words to the poem itself as a symbol reflecting the entire poetic universe. This broad definition permits Frye to associate the appropriate kind of symbolism with each phase, and thereby to define the phase at the highest level of generality. The symbol used as a sign results in the descriptive phase; as motif, in the literal phase; as image, in the formal phase; as archetype, in the mythical phase; and as monad, in the anagogic phase.

The other primary categories which underlie Frye’s definition of the phases are narrative (or mythos) and meaning (or dianoia). These terms also have a wide range of reference, much wider even than in the First Essay. One can only indicate the general associations they have in Frye’s usage. Narrative is associated with rhythm, movement, recurrence, event, and ritual. Meaning is associated with pattern, structure, stasis, precept, and dream. The meaning of “narrative” and the meaning of “meaning,” then, always change according to the context of Frye’s discussion. The central role which this pair of terms comes to assume in the Anatomy, as well as in Frye’s other work, cannot be overemphasized.

The correlation which Frye makes between the five phases and {33} their respective symbols, narratives, and meanings, as well as the relation among the phases and several other categories, is set down, as a kind of visual shorthand for the discussion which follows, in Figure 3.

| Literal | Descriptive | Formal | Mythical | Anagogic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Figure 3. The phases of symbolism {p. 35} |

|||||

| Type of Symbol | Motif |

Sign |

Image |

Archetype |

Monad |

| Narrative (Mythos) |

Rhythm or movement of words; flow of particular sounds |

Relation of order of words to life; imitations of real events |

Typical event or example Shaping principle |

Ritual: recurrent act of symbolic communication |

Total ritual of man, or unlimited social action |

| Meaning (Dianoia) |

Pattern or structural unity; ambiguous and complex verbal pattern |

Relation of pattern to assertive propositions; imitation of objects or propositions |

Typical precept Containing principle |

Dream: conflict of desire and reality |

Total dream of man, or unlimited human desire |

| Related Kind of Art | Symbolisme |

Realism and naturalism |

Neoclassical art |

Primitive and popular writing |

Scripture, apocalyptic revelation |

| Related Kind of Criticism | “Textural” or New Criticism |

Historical and documentary criticism |

Commentary or interpretation |

Archetypal criticism (convention and genre) |

Anagogic criticism (connected with religion) |

| Medieval Level | Literal or historical |

Allegorical |

Moral or tropical |

Anagogic |

|

| Parallel Mode | Thematic irony |

Low mimesis |

High mimesis |

Romance |

Myth |

The Taxonomy of Symbolism

The Literal and Descriptive Phases The first two of Frye’s contexts, the literal and descriptive phases, are linked together in his discussion because, unlike the other three phases, they are defined in relation to each other. The method is one of dichotomous division whereby Frye sets up a series of opposing terms within the triadic framework (symbol-narrative-meaning), outlined above. The opposing sets of categories are then used to define, or give content to, the terms “literal” and “descriptive.”

The opposing terms of the first category (symbol) are motif and sign, which represent the kinds of signification which the literal and descriptive phases respectively embody. These two words are defined in turn by another series of opposing qualities. When the symbol is a sign, the movement of reference is centrifugal, as in descriptive or assertive works; and when the symbol is a motif, the movement is centripetal, as in imaginative, or in what Frye calls “hypothetical” works. Similarly, in the former case, where allegiance is to the reality principle, value is instrumental and priority is given to instruction; and in the latter, where allegiance is to the pleasure principle, value is final and priority is given to delight.

Underlying Frye’s distinction between the “narrative” and “meaning” poles of the dichotomy is an assumption, fundamental to other parts of Anatomy of Criticism, that all art possesses both a temporal and a spatial dimension. Frye refers to the temporal or narrative dimension of the literal phase as rhythm, and the narrative movement of the descriptive phase is the relation which the order of words has to external reality. Similarly, when the spatial aspect is more important in our experience of a work, we tend to view it statically as an integrated unit, or to use Frye’s chief metaphors, as pattern or structure. Thus he is led to describe a poem’s meaning in the literal phase as “its pattern or integrity as a verbal structure. Its words cannot be separated and attached to sign-values: all possible sign-values of a word are absorbed into a complexity of verbal relationships.” On the other hand, a poem’s meaning in the descriptive phase is “the relation of its pattern to a body of assertive propositions, and the conception of symbolism involved is the one which literature has in common, not with the arts, but with other structures in words” (AC, 78).

As indicated in Figure 3, each of the phases of symbolism has an {34} affinity to both a certain kind of literature and a typical critical procedure. This relation for the descriptive and literal phases of literature can be represented by a continuum running from documentary naturalism at one pole to symbolisme and “pure” poetry at the other. Although every work of literature is characterized by both these phases of symbolism, there can be an infinite number of variations along the descriptive-literal axis, since a given work tends to be influenced more deeply by one phase than the other. Thus when the descriptive phase predominates, the narrative of literature tends toward realism, and its meaning toward the didactic or descriptive. The limits, at this end of the continuum, would be represented by such writers as Zola and Dreiser, whose work “goes about as far as a representation of life, to be judged by its accuracy of description rather than by its integrity as a structure of words, as it could go and still remain literature” (AC, 80). At the other end, as a complement to naturalism, is the tradition of writers like Mallarmé, Rimbaud, Rilke, Pound, and Eliot. Here the emphasis is on the literal phase of meaning: literature becomes a “centripetal verbal pattern, in which elements of direct or verifiable statement are subordinated to the integrity of that pattern” (AC, 80). Criticism, says Frye, was able to achieve an acceptable theory of literal meaning only after the development of symbolisme (AC, 80).

In a similar fashion, the literal and descriptive phases are reflected in two chief types of criticism. Related to the descriptive aspect of a symbol, on the one hand, are the various kinds of documentary criticism which deal with sources, historical transmission, the history of ideas, and the like. Such approaches assume that a poem is a verbal document whose “imaginative hypothesis” can be made explicit by assertive or prepositional language. A literal criticism, on the other hand, will find in poetry “a subtle and elusive verbal pattern” that neither leads to nor permits simple assertive statements or prose paraphrases. As Frye’s language here suggests, this tendency is represented by New Criticism, an approach which is based

on the conception of a poem as literally a poem. It studies the symbolism of a poem as an ambiguous structure of interlocking motifs; it sees the poetic pattern of meaning as a self-contained “texture,” and it thinks of the external relations of a poem as being with the other arts, to be approached only with the Horatian warning of favete linguis, and not with the historical or I lie didactic. The word texture, with its overtones of a complicated surface, is the most expressive one for this approach.2

Frye’s indebtedness to the terms and distinctions of contemporary poetics is obvious here. In fact, the principal assumption underlying his {36} analysis of the descriptive and literal phases is one he shares with the major proponents of the New Criticism, those whose concern has been to locate the meaning of poetry in the nature of its symbolic language. Frye’s distinction between assertive and hypothetic meaning is closely akin, for example, to Cleanth Brooks’s opposition between factual and emotional language; to I.A. Richards’s emotive-referential dialectic; to the distinction in John Crowe Ransom between rational and poetic meaning, or in Philip Wheelwright between steno-language and depth-language; to the opposition in William Empson between clarity and ambiguity; or, finally, to the procedure running throughout contemporary criticism, which attempts to separate poetic language from that of either ordinary usage or science on the basis of the more complex, ambiguous, and ironic meaning of the former. The characteristic method of inference in each of these procedures, as R.S. Crane observes, is based on a similar dialectic; for they all, Frye included, employ a process of reasoning to what the language and meaning of poetry are from what assertive discourse and rational meaning are not.3

Frye would like to refute the semantic analysis of logical positivism, that is, the reduction of all meaning to either rational or emotional discourse.

Some philosophers who assume that all meaning is descriptive meaning tell us that, as a poem does not describe things rationally, it must be a description of an emotion. According to this the literal core of poetry would be a cri de coeur, . . . the direct statement of a nervous organism confronted with something that seems to demand an emotional response, like a dog howling at the moon. . . . We have found, however, that the real core of poetry is a subtle and elusive verbal pattern that avoids, and does not lead to, such bald statements. (AC, 81)

While it is true that the subtlety and the range of reference in Frye’s discussion of the literal phase will not permit a simple equation between the meaning expressed by symbols in this phase and the nondescriptive meaning of the analytic philosophers, it is no less true that he still remains within the framework of the theory he opposes; what he does is to convert his denial of the principles of linguistic philosophy into the principles of his own poetic theory. The primary assumptions remain the same: poetry, in the literal and descriptive phases, is primarily a mode of discourse and there is a bipolar distribution of all language and thus of all meaning.4

The first section of Frye’s theory of symbols results in an expansion and rearrangement of the medieval scheme of four levels of interpretation, according to which literal meaning is discursive or {37} representational meaning. Its point of reference is centrifugal. When Dante interprets scripture literally, he points to the correspondence between an event in the Bible and a historical event, or at least one he assumed to have occurred in the past. In this sense, literature signifies real events. The first medieval level of symbolism thus becomes Frye’s descriptive level. His own literal phase, however, has no corresponding rung on the medieval ladder. The advantage of rearranging the categories, Frye believes, is that he now has a framework to account for a poem literally as a poem—as a self-contained verbal structure whose meaning is not dependent upon any external reference. This redesignation is simply one more way that Frye can indicate the difference between a symbol as motif and sign. As a principle of Frye’s system, it reveals the dialectical method he uses to define poetic meaning. He is not satisfied, however, with the dichotomy, calling it a “quizzical antithesis between delight and instruction, ironic withdrawal from reality and explicit connection with it” (AC, 82). Therefore, in his discussion of the third phase of symbolism he attempts to move beyond these now-familiar distinctions of the New Criticism.

The Formal Phase This phase of symbolism relates specifically to the imagery of poetry. Yet formal criticism can be seen as studying literature from the point of view, once again, of either mythos or dianoia. The meaning of these two terms remains fairly close to the meaning they had in Frye’s discussion of the literal and descriptive phases, though here they function differently. In the first two phases, narrative (mythos) and meaning (dianoia) tended to diverge, in Frye’s argument, toward opposite poles. In the formal phase, however, his interest is in making them converge until they are somehow unified, for it is the essential unity of a work of art which the word “form” is usually meant to convey.

Frye’s explanation of this point involves a highly complex dialectic. First of all, he uses the concept of imitation to contravene the form-content dichotomy. Mythos, he says, is a secondary imitation of an action because it describes typical rather than specific human acts. And dianoia is a secondary imitation of thought because it also is concerned with the typical, in this case, “with images, metaphors, diagrams, and verbal ambiguities out of which specific ideas develop” (AC, 83). The assumption underlying the argument, apparently, is that the concept of secondary imitation, because it represents the typical, is a principle which unities formal criticism and thus permits the discussion of poetry on this level always to remain internal. In formal imitation, Frye says, “the work of art does not reflect external events and ideas, but exists between the example and the precept” (AC, 84). Or again, “The central {38} principle of the formal phase, that a poem is an imitation of nature, is . . . a principle which isolates the individual poem” (AC, 95). Frye’s argument depends on using the concept of typicality to avoid the antithesis implicit in the literal and descriptive phases. Yet Frye’s use of the word “typical” is equivocal: more philosohical than history on the one hand, and more historical than philosophy on the other.

The second argument for the unity of formal criticism is based upon the movement-stasis dichotomy, analogized once again to the terms mythos and dianoia. Every detail of a poem is related to its form, Frye claims, and this form remains the same “whether it is examined as stationary or as moving through the work from beginning to end” (AC, 83). His main point is that we need to balance the ordinary method of studying symbolism, which is solely in terms of meaning, with the study of a poem’s moving body of imagery. “The form of a poem is the same whether it is studied as narrative or as meaning, hence the structure of imagery in Macbeth may be studied as a pattern derived from the text, or as a rhythm of repetition falling on an audience’s ear” (AC, 85). The method of definition here continues to rely upon the principle of dichotomous division: mythos versus dianoia, movement versus stasis, narrative versus meaning, structure versus rhythm, shaping form versus containing form (AC, 82–85). Yet the way these pairs of opposites function, as compared with their use in the previous section, is that they do not point to realities outside the poem. Poets do not directly imitate either nature or thought; they create potential, hypothetical, and typical forms. It is this conception of art which Frye also sees as helping to resolve the split between delight and instruction, form and content.

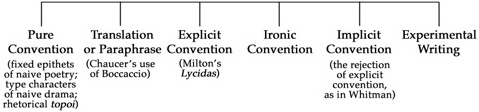

Criticism in the formal phase is called commentary, “the process of translating into explicit or discursive language what is implicit in the poem” (AC, 86). More specifically, it tries to isolate the ideas embodied in the structure of poetic imagery. This produces allegorical interpretation, and, in fact, commentary sees all literature as potential allegory (AC, 89). The range of symbolism in the formal phase (“thematically significant imagery”) can be classified according to the degree of its explicitness. All literature, in other words, can be organized along a continuum of formal meaning, from the most to the least allegorical, as in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Degrees of allegorical explicitness (formal phase). {p. 38} |

{39} The criterion here is the degree to which a writer insists on relating his imagery to precepts and examples. Naive allegory is so close to discursive writing that it can hardly be called literature at all. It “belongs chiefly to educational literature on an elementary level: schoolroom moralities, devotional exempla, local pageants, and the like” (AC, 90). Even though such naive forms have no real hypothetical center, they are considered allegorical to some degree since they occasionally rely upon images to illustrate their theses.

The two types of actual or formal allegory, continuous and freistimmige, show an explicit connection between image and idea, differing only in that the former is more overt and systematic. Dante, Spenser, and Bunyan, for example, maintain the allegorical connections throughout their work, whereas in writers like Hawthorne, Goethe, and Ibsen the symbolic equations are at once less explicit and less continuous.5 If the structure of the poetic imagery has a strong doctrinal emphasis, so that the internal fictions become exempla, as in Milton’s epics, a fourth kind of allegorical relation is established. And to the right of this, located at the “center” of the scale, are “works in which the structure of imagery, however suggestive, has an implicit relation only to events and ideas, and which includes the bulk of Shakespeare” (AC, 91). All other poetic imagery tends increasingly toward the ironic and paradoxical end of the continuum; it includes the kind of symbolism implied by the metaphysical conceit and symbolisme, by Eliot’s objective correlative and the heraldic emblem. Frye refers to this latter kind of imagery (e.g., Melville’s whale and Virginia Woolf’s lighthouse) as ironic or paradoxical because as units of meaning the symbols arrest the narrative, and as units of narrative they perplex the meaning. Beyond this mode, at the extreme right of the continuum, are indirect symbolic techniques, like private association, Dadaism, and intentionally confounding symbols.

What Frye has done is to redefine the word “allegory,” or at least greatly expand its ordinary meaning; for he uses the term not only to refer to a literary convention but also to indicate a universal structural principle of literature. It is universal because Frye sees all literature in relation to mythos and dianoia. We engage in allegorical interpretation, in other words, whenever we relate the events of a narrative to conceptual terminology. This is commentary, or the translation of poetic into discursive meaning. In interpreting an “actual” or continuous allegory like The Faerie Queene, the relationship between mythos and dianoia is so explicit that it prescribes the direction which commentary must take. In a work like Hamlet the relationship is more implicit. Yet commentary on Hamlet, for Frye, is still allegorical: if we interpret Hamlet, say, as a tragedy of indecision, we begin to set up the kind of moral counterpart {40} (dianoia) to the events of its narrative (mythos) that continuous allegory has as a part of its structure. We should expect, then, that as allegory becomes more implicit, the direction that the commentary must go becomes less prescriptive. And this is precisely Frye’s position: an implicit allegory like Hamlet can carry an almost infinite number of interpretations.6

The Mythical Phase If in the formal phase a poem is considered as representing its own class, a unique artifact lying midway between precept and example, in the mythical phase it is seen generically, one of a whole group of similar forms. The fundamental principle here is Frye’s assumption regarding the total order of words, for the study of poetry involves not simply isolating the poem as an imitation of nature but also considering it as an imitation of other poems. And since literature shapes itself out of the total order of words, the study of genres becomes important. Frye reserves his treatment of genres for the Fourth Essay, concentrating here upon convention, the principle which ultimately provides the basis for the study of genres. He emphasizes the conventionalized aspect of art not only because it is close to his own interests, both as a theoretical and a practical critic, but also because he believes literary convention has been neglected by criticism. Thus he spends some time elaborating a number of his basic convictions: the more original art is, the more profoundly imitative it is of other art; we have all been schooled in low-mimetic prejudices about the creative process; the conventional aspect of poetry is as important as what is distinctive in poetic achievement.

The symbol which characterizes the fourth phase is, of course, the conventional symbol, or what Frye calls the “archetype.” Poetry, he says in a passage that points directly toward the Third and Fourth Essays, is not simply

an aggregate of artifacts imitating nature, but one of the activities of human artifice taken as a whole. If we may use the word “civilization” for this, we may say that our fourth phase looks at poetry as one of the techniques of civilization. It is concerned, therefore, with the social aspect of poetry, with poetry as the focus of a community. The symbol in this phase is the communicable unit, to which I give the name archetype: that is, a typical or recurring image. I mean by an archetype a symbol which connects one poem with another and thereby helps to unify and integrate our literary experience. And as the archetype is the communicable symbol, archetypal criticism is primarily concerned with literature as a social fact and as a mode of communication. By the study of conventions and genres, it attempts to fit poems into the body of poetry as a whole. (AC, 99)

{41} The study of convention is based upon analogies. In the case of genres, it is analogies of form; in the case of archetypes, analogies of symbolism. To see Moby Dick, for example, as an archetype is to recognize an analogy between Melville’s whale and other “leviathans and dragons of the deep from the Old Testament onward” (AC, 100). He is but one of a recurring tradition of such creatures which are clustered together in our experience of literature; such images come together in our imaginative experience, Frye argues, because of their similarities. Another example is the use of a dark and light heroine, a common convention of nineteenth-century fiction. The dark heroine, he says, “is as a rule passionate, haughty, plain, foreign or Jewish, and in some way associated with the undesirable or with some kind of forbidden fruit like incest. When the two are involved with the same hero, the plot usually has to get rid of the dark one or make her into a sister if the story is to end happily” (AC, 101). Frye sees this archetype recurring in countless stories, including those of Sir Walter Scott, James Fenimore Cooper, Wilkie Collins, Poe, Melville, and Hawthorne; there is even a male version of the convention in Wuthering Heights (AC, 101).

Frye observes that the function of signs also depends on conventional associations. But the difference between signs and archetypes is that the latter are complex variables, which means that a given archetype may symbolize a variety of objects, ideas, or emotions. “Green,” for example, “may symbolize hope or vegetable nature or a go sign in traffic or Irish patriotism as easily as jealousy, but the word green as a verbal sign always refers to a certain color” (AC, 102). Some archetypal associations are more obvious than others, even though there are no necessary connections, “no intrinsic or inherent correspondences which must invariably be present” (AC, 103). But archetypes are not only complex; they also vary in explicitness. Frye sees these relations as a scale, running from pure convention at one extreme to pure variable at the other, as in figure 5. This range of conventions should not be confused with the scale of allegorical meanings in the third phase; the two scales are parallel only insofar as their common principle is the degree of explicitness which images and archetypes, respectively, have. As Figure 5 indicates, the most highly conventionalized literature is likely to be naive (i.e., primitive or popular). It would follow then that archetypes are easiest to study, because more obvious and explicit, in naive forms; which is one reason for Frye’s frequent attention to primitive and popular forms of art.7

Figure 5. Degrees of archetypal convention (mythical phase). {p. 42} |

|

The symbol as archetype is the first principle underlying Frye’s definition of the fourth phase. How do the categories mythos and dianoia function in this definition? The pairs of opposites in his dialectic now become recurrence and desire, and ritual and myth. Relating these {42} terms to mythos and dianoia depends once more on some highly abstract reasoning. The transition comes in this passage:

Every phase of symbolism has its particular approach to narrative and to meaning. In the literal phase, narrative is a flow of significant sounds, and meaning an ambiguous and complex verbal pattern. In the descriptive phase, narrative is an imitation of real events, and meaning an imitation of actual objects or propositions. In the formal phase, poetry exists between the example and the precept. In the exemplary event there is an element of recurrence; in the precept, or statement about what ought to be, there is a strong element of desire, or what is called “wish-thinking.” These elements of recurrence and desire come into the foreground in archetypal criticism, which studies poems as units of poetry as a whole and symbols as units of communication. From such a point of view, the narrative aspect of literature is a recurrent act of symbolic communication: in other words a ritual. . . . [and] the significant content is the conflict of desire and reality which has for its basis the work of the dream. Ritual and dream, therefore, are the narrative [mythos] and significant content [dianoia] respectively of literature in its archetypal aspect. (AC, 104–5)

The method of reasoning by which Frye reaches the “therefore” in the final sentence is analogical. That ritual is the narrative aspect of the archetypal phase follows only because ritual is defined as a recurrent act of symbolic communication. The quality of recurrence, in other words, is what narrative and ritual have in common. How then does Frye arrive at the principle of recurrence? To a degree it is present in his initial definition of narrative in the literal phase, where mythos is seen as rhythm, or the recurrent movement of words. But in the formal phase, recurrence as an aspect of mythos disappears altogether from his discussion. One might argue that the principle of recurrence is {43} implicit, in the formal phase, in Frye’s account of typical actions; but this hardly explains why typical is used to characterize both narrative and meaning. The “example” is the formal aspect of narrative, and the temporal association Frye makes is to see mythos as a moving body of imagery. But in order to keep his categories consistent, that is, to make “recurrence” a principle of narrative throughout each of the phases, Frye must find some way of reintroducing it into the formal phase, for this will provide a means of transition to ritual. He does this by simply asserting that in “the exemplary event there is an element of recurrence,” which is true insofar as we desire the exemplary event to be imitated again and again. The point is, however, that recurrence is maintained as the basic category by an analogical leap from the literal to the mythical phase, bypassing the formal phase.

Frye employs the same kind of dialectic in moving from the precept of the formal phase to the dream of the mythical. Here the transition is based on the assertion that there is a strong element of desire associated with the precept, so that desire becomes the mediating category between the third and fourth phases. Putting it straightforwardly, the form of the argument is this: Desire is related to precept; precept is the dianoia of formal criticism. Desire is related to dream; dream is the dianoia of archetypal criticism. The relationship, of course, is again analogical.

Once Frye has distinguished ritual and dream, which on the archetypal level represent mythos and dianoia respectively, he seeks to unite them under the category of myth. The archetypal study of narrative, he says, deals with “the generic, recurring, or conventional actions which show analogies to rituals: the weddings, funerals, intellectual and social initiations, executions or mock executions, the chasing away of the scapegoat villain, and so on”; whereas the archetypal study of dianoia treats the generic, recurring, or conventional “shape” of a work, “indicated by its mood and resolution, whether tragic, comic, ironic, or what not, in which the relationship of desire and experience is expressed” (AC, 105). Specific illustrations of this kind of study are found in the Third Essay. At this point Frye wants to show the relationship between ritual and dream, neither of which is literary, to a single form of verbal communication. This form is myth, which explains the title of the fourth phase. From the perspective of the mythical phase, Frye argues, we see the same kinds of processes or rhythms occurring in literature that we find in ritual and dream. There are two basic patterns; one cyclical, the other dialectical. Ritual imitates the cyclical process of nature: the rhythmic movement of the universe and the seasons, as well as the recurring cycles of human life; and literature in the archetypal phase imitates nature in the same way. The dialectical pattern, on the other hand, {44} derives from the world of dream, where desire is in constant conflict with reality. Liberation and capture, integration and expulsion, love and hate are some of the terms we apply to this moral dialectic in ritual and dream.8 The same pattern, when it is expressed hypothetically, is to be found in poetry. Archetypal criticism, Frye concludes, is based upon these two organizing patterns (AC, 105–6).

Frye’s indebtedness to contemporary anthropology and psychology is apparent in these distinctions, resonating as they do with the language of Frazer, Freud, and Jung. But Frye is careful to emphasize the distinction between the aims of criticism and those of these other disciplines. The critic, he says, “is concerned only with ritual or dream patterns which are actually in what he is studying, however they got there” (AC, 109). Some archetypal critics, he adds, do not recognize this, having been misled into searching for the origins of the ritual elements of literature. His point is not that such studies have no place in criticism but that they belong on the descriptive rather than the archetypal level. What is at stake here is distinguishing clearly between the history of literary works and the genre to which they belong. Frye apparently has his eye on scholars like Gilbert Murray, who maintained that in tragedy there survives an ancient ritual involving a combat between the old year-spirit and the new; or F.M. Cornford, who extended Murray’s thesis to Greek comedy, arguing that the basic pattern of the Aristophanic play can be directly traced to primitive seasonal rituals, such as the Combat, Sacred Marriage, and Beanfeast. Frye is not saying that Murray and the Cambridge anthropologists were wrong, even though it may be incorrect to assume that a given Greek play actually descends from a ritual libretto. He is saying, rather, that for the archetypal critic the question is irrelevant. On the other hand, Frye would not deny that a Greek play could have been conditioned by standard patterns of ritual or that its conventions were determined by actual performances. What is at issue, in other words, is not the dependence of a given play upon an actual performance, but simply a parallelism between narrative and ritual patterns, or between the conventions and genres of literature and those of ritual ceremony. The archetypal critic, Frye would say, is concerned only with this latter question. The historical critic may be concerned with the former.9

Frye’s position on the application of psychology to literature is similar: the archetypal critic will not want to confuse biography with criticism. The repetition of a certain pattern in Shakespeare’s plays, he says, may be studied in various ways. “If Shakespeare is unique or anomalous, or even exceptional, in using this pattern, the reason for his use of it may be at least partly psychological” (AC, 111), and critics may, at the descriptive level, resort to psychological theory in attempting to explain it. {45} The archetypal critic, however, can pursue the problem only when the same pattern is recognized in Shakespeare’s contemporaries or in the dramatists of different ages and cultures, in which case convention and genre become the important considerations (AC, 111).

In an early essay on the nature of symbolism Frye says that “wherever we have archetypal symbolism, we pass from the question ‘What does this symbol, sea or tree or serpent or character, mean in this work of art?’ to the question ‘What does it mean in my imaginative comprehension of such things as a whole?’ Thus the presence of archetypal symbolism makes the individual poem, not its own object, but a phase of imaginative experience.”10 Archetypal symbolism works in two directions for Frye. On the one hand, because the language of myth and symbol enters and informs all verbal culture, he uses what he has learned about symbolism as a literary critic to understand and interpret texts in philosophy, psychology, history, and comparative religion. On the other hand, he sees these disciplines as informing literary criticism itself. Thus he can approach Toynbee’s Study of History from the centrifugal perspective, seeing it as “an intuitive response based on an imaginative grasp of the symbolic significance of certain data” (CL, 80). The book can be read, then, not as a factual chronicle which is trying to prove something by its massive accumulation of data but as a grand imaginative vision. Similarly, Frye approaches Frazer’s Golden Bough as if it were an encyclopaedic epic or a continuous form of prose fiction. It is, he says, really “about what the human imagination does when it tries to express itself about the greatest mysteries” (CL, 89).

But Frye also works in a centripetal direction. Cassirer, Spengler, Frazer, Jung, and Eliade are themselves students of symbolism whose works provide us with a grammar of the human imagination. Cassirer’s symbolic forms, like those found in literature, take their structure from the mind and their content from the natural world. And Frazer’s expansive collections of material, because they give us a grammar of unconscious symbolism on both its personal and its social sides, will be of greater benefit to the poet and literary critic than to the anthropologist. Thus The Golden Bough, like Jung’s Psychology of the Unconscious, becomes primarily a work of literary criticism. Similarly, Eliade’s studies in Religionsgeschichte are especially important for the literary critic because they provide a grammar of initiatory and comparative symbolism.

The two perspectives—the centrifugal and the centripetal—do not finally move in opposite directions in Frye’s work. They interpenetrate, to use his familiar metaphor. In a review of Jung’s Psychology of the Unconscious, Frye develops a view of criticism which makes its way later, some of it verbatim, into his account of the archetypal phase of {46} symbolism in the Anatomy. But this is not to say that Frye is a Jungian. His view has always been that criticism needs to be independent from externally derived frameworks—what he calls “determinisms.” “Critical principles,” he says, “cannot be taken over ready-made from theology, philosophy, politics, science, or any combination of these” (AC, 7). Yet Frye himself, as the Second Essay bears ample witness, has appropriated a number of concepts from other disciplines, especially from psychology and anthropology.

The choice of metaphors used to describe the relation of one subject to another is, Frye says, “a fateful choice” (SM, 106). His own choice of “interpenetration” avoids the determinism implicit in such vertical metaphors as “founded upon” and in such horizonal ones as “connected” or “united.” The first “means that we have to get something established in another subject ‘before’ we can study literature, which of course means that we never get to study literature at all”; whereas the second means that by trying to build bridges between different subjects we destroy the context of them both (SM, 106–7). There should be no problem, then, in understanding Frye’s relation to someone like Jung.

I am continually asked . . . about my relation to Jung, and especially about the relation of my use of the word “archetype” to his. So far I have tended to resist the association, because in my experience whenever anyone mentions it his next sentence is almost certain to be nonsense. . . . It seems strange to overlook the possibility that the arts, including literature, might just conceivably be what they have always been taken to be, possible techniques of meditation, in the strictest sense of the word, ways of cultivating, focussing and ordering one’s mental processes on the basis of symbol rather than concept. (SM, 117)

This is the reason that Frye can say that Jung’s work is “a grammar of literary symbolism which for all serious students of literature is as important as it is endlessly fascinating” (CL, 129).

To see archetypal criticism as concerned with the social aspects of poetry is, as Frye says, to emphasize the relationship of the individual poem to other poems. But this is only half of what should properly be emphasized, for a poem is also a “part of the total human imitation of nature that we call civilization” (AC, 105; see also 99, 112–13). What does it mean to say that civilization is a total human imitation of nature, an idea which recurs frequently in Frye’s work? He himself refers to it metaphorically as “the process of making a total human form out of nature” (AC, 105, 112). He means that as civilization develops, the natural world is transformed from the nonhuman into something with {47} human shape and meaning. This process is given direction by desire. Because man is not satisfied, for example, with roots and caves, his civilization creates “human forms of nature” in farming and architecture. This kind of desire, Frye says,

is thus not a simple response to need, for an animal may need food without planting a garden to get it, nor is it a simple response to want, or desire/or something in particular. It is neither limited to nor satisfied by objects, but is the energy that leads human society to develop its own form. Desire in this sense is the social aspect of what we met on the literal level as emotion, an impulse toward expression which would have remained amorphous if the poem had not liberated it by providing the form of its expression. The form of desire, similarly, is liberated and made apparent by civilization. The efficient cause of civilization is work, and poetry in its social aspect has the function of expressing, as a verbal hypothesis, a vision of the goal of work and the forms of desire. (AC, 105–6)

Criticism on the archetypal level therefore is concerned not just with genre and convention. Because it views the symbol as a natural object with a human meaning, its scope is expanded to include civilization. And from this perspective, poetry becomes a product of a vision of the goals of human work. (The Blakean influence behind these ideas, especially the concept of civilization as a “human form,” is a point to which we shall return shortly.)

This view, says Frye, makes it tempting for the archetypal critic to see art as an ethical instrument whose function is to serve society by visualizing its goals. Similarly, in the descriptive phase we are likely to encounter truth as an external goal for art, and in the literal and formal phases, beauty. But, Frye argues, as none of these external standards can ultimately determine the value of literature, we need to move beyond the archetypal phase and the goals of civilization, where art is not an end in itself, “to culture, where it is disinterested and liberal, and stands on its own feet” (AC, 115). By such passage, we climb to the anagogic level.

The Anagogic Phase The anagogic phase is Frye’s beatific critical vision. Its argument is more difficult because more visionary. Its Blakean language has caused the response of some readers to sound like Pound’s dismissal of the medieval fourth level: “Anagogical? Hell’s bells, ‘nobody’ knows what THAT is.”11 This kind of reaction is perhaps understandable if Frye’s statements about the anagogic phase are taken out of context, as the following quotations should illustrate:

{48} Nature is now [in the fifth phase] inside the mind of an infinite man who builds his cities out of the Milky Way. This is not reality, but it is the conceivable or imaginative limit of desire, which is infinite, eternal, and hence apocalyptic. By an apocalypse I mean primarily the imaginative conception of the whole of nature as the content of an infinite and eternal living body which, if not human, is closer to being human than to being inanimate. (AC, 119)

Anagogically, then, the symbol is a monad, all symbols being united in a single infinite and eternal verbal symbol which is, as dianoia, the Logos, and, as mythos, total creative act. (AC, 121)

The study of literature takes us toward seeing poetry as the imitation of infinite social action and infinite human thought, the mind of man who is all men, the universal creative word which is all words. (AC, 125)

Unless seen in context, these passages approach the limits of intelligibility. The problem, then, is to understand these statements in the framework of Frye’s discourse.

Frye begins by drawing an analogy between his anagogic phase and the medieval fourth level. He defines anagogy as “universal meaning,” a definition which, although not exactly consistent with medieval usage, is important in Frye’s description of the anagogic symbol.12 The second analogy is a parallel between the fifth phase and fifth mode of Frye’s own framework. Both are concerned with the mythopoeic aspect of literature, that is, with “fictions and themes relating to divine or quasi-divine beings and powers.” These two analogies should alert us to expect a description of the anagogic phase which draws upon religious or visionary language.13

The analogy to myth having been drawn, Frye can now move toward the principle upon which the fifth phase is said to rest, namely, that there is a center to the order of words. That such a center exists is predicated on the assumption that our “greatest” literary experiences derive from works which are the most mythopoeic (AC, 117). These are, at one end, primitive and popular works, both of which afford “an unobstructed view of archetypes,” and, at the other, the learned and recondite mythopoeia in writers like Dante, Spenser, James, and Joyce. “The inference,” Frye says, “seems to be that the learned and the subtle, like the primitive and the popular, tend toward a center of imaginative experience” (AC, 117). T he crux of the matter comes in this heavily value-laden statement:

In the greatest moments of Dante and Shakespeare, in, say The Tempest or the climax of the Purgatorio, we have a feeling of {49} converging significance, the feeling that here we are close to seeing what our whole literary experience has been about, the feeling that we have moved into the still center of the order of words. Criticism as knowledge, the criticism which is compelled to keep on talking about the subject, recognizes the fact thai there is a center of the order of words. (AC, 117–18)

Frye realizes the difficulties attendant on such a view; he therefore faces the problem of defining the norm for the order of words—the “still point” around which his literary universe revolves.

The first and most obvious basis for Frye’s position is his own literary experience, the feeling he has of being at the center of significance when in the presence of the greatest works of literature.14 In the second place, the idea of a center to the order of words is consistent with, even a logical consequence of, the imagery Frye has already used to describe the structure of literature. If the literary modes are cyclical and if the critical phases are parallel to the modes, then it stands to reason that the cycle must have a center. In short, the notion of “converging significance” does not fit well into a strictly linear paradigm. More important than this, however, is the idea of order itself. If literature does constitute a total order, then there must be some principle holding it together. We have already seen Frye assert that the function of the archetypal critic (in the fourth phase) is to search out those principles of structure which works of literature have in common. This kind of study, however, tells us nothing about the structure of literature as a whole; therefore, unless we can find some unifying principle for the total order, the study of genres and conventions will be nothing more than “an endless series of free associations” (AC, 118). In other words, one can never arrive at the self-contained whole, which is literature itself, simply by studying archetypes, for as symbols they represent only parts of the whole. The existence of a total order among all literary works is the prior assumption, therefore, which makes it necessary for Frye to establish a norm underlying the order. And this norm is the center, the “still point” around which his literary universe revolves.

Having asserted the existence of a unifying principle, Frye’s problem becomes trying to define it. His first recourse is to the categories which have been used continually, though not univocally, throughout the Second Essay: symbol, mythos, and dianoia. The symbols of the anagogic phase are “universal symbols”: “I do not mean by this phrase,” Frye says, “that there is any archetypal code book which has been memorized by all human societies without exception. I mean that some symbols are images of things common to all men” (AC, 118). This being the case, then some symbols have a limitless range of reference: {50} their power to communicate is not bound by nature or history. It is this illimitable aspect of the anagogic symbol that Frye’s definition fastens upon. The dianoia and mythos of the mythical phase were respectively dream and ritual. Expanding these categories to define the symbol of the anagogic phase, Frye says that “literature imitates the total dream of man, and so imitates the thought of a human mind which is at the circumference and not at the center of its reality” (AC, 119). This is the “meaning” pole of Frye’s dialectic. At the other pole, representing “narrative,” poetry is said to imitate “human action as total ritual, and so [to imitate] the action of an omnipotent human society that contains all the powers of nature within itself” (AC, 120). Unlimited social action (or total ritual) and unlimited individual thought (or total dream) are the dialectical opposites, therefore, which unite to produce the macro-cosmic aspect of the anagogic phase. This centrifugal movement, extending indefinitely outward toward a periphery where there are no limits to the intelligibility of a symbol, is but one of the aspects of the anagogic symbol, the macrocosm of total ritual and dream. The other, as we have seen, is the centripetal movement, turning inward toward the center of the literary universe, or toward the microcosm, which is “whatever poem we happen to be reading” (AC, 121). Seen together, these two movements produce the anagogic symbol, or what Frye calls the “monad” (AC, 121). T his is a paradoxical concept, but only in the sense that an expression like “concrete universal” is also paradoxical, for “monad” refers to the individual poem which manifests or reflects within itself the entire poetic universe.

The Blakean Influence

The figure of William Blake looms large behind Frye’s thought in this section, a more important influence than the one brief allusion to him might suggest. In a prefatory note Frye tells us that he learned his principles of literary symbolism and Biblical typology from Blake in the first place (AC, vii). And when Frye refers to the “imaginative limit of desire” and to the apocalypse as “the imaginative conception of the whole of nature as the content of an infinite and eternal living body” (AC, 119), he is using the same kind of language he used in Fearful Symmetry to describe the implications of Blake’s view of poetry. In Frye’s understanding of Blake, in fact, we begin to strike close to the heart of a number of his fundamental convictions: his Romantic aesthetic, his conviction that critical principles derive ultimately from poetic vision, his belief in the possibility of a cultural synthesis. An understanding of Frye’s indebtedness to Blake should help illuminate what he means by the fifth phase of svmbolism.

{51} In the history of discourse about literature most critics have derived the deductive foundations of their critical theories from philosophers, or from other critics, or from what might be called broadly the speculative and discursive currents of thought prevalent at the time.15 Frye is a notable exception to this tendency, having derived a number of his most important critical principles from the study of poets themselves. This fact is apparent at a number of places in his writings, not the least of which is in his discussion of fifth-phase symbolism. “Anagogic criticism,” he says, “is usually found in direct connection with religion, and is to be discovered chiefly in the more uninhibited utterances of poets themselves” (AC, 122). It is important not to overlook what is being proposed here. Frye is not saying that anagogic symbols can be found in uninhibited poetry, though doubtless he would make this claim in another context. He is saying rather that if we really want to know what anagogic criticism is, then we have to turn to the poetry of the more uninhibited writers. In other words, at the anagogic level poetry is criticism and criticism is poetry. We find anagogic criticism, to give some of Frye’s examples, “in those passages of Eliot’s quartets where the words of the poet are placed within the context of the incarnate Word . . . in Valéry’s conception of a total intelligence which appears more fancifully in his figure of M. Teste; in Yeats’s cryptic utterances about the artifice of eternity . . . in Dylan Thomas’s exultant hymns to a universal human body” (AC, 122). Frye does not include Blake among his examples at this point, but ten years earlier in his book on Blake’s prophecies he had come to the same conclusion, namely, that the solution to deciphering Blake’s symbolic code lay within literature itself. Some of the principles of this book, Fearful Symmetry, will provide a useful commentary on Frye’s discussion of the anagogic phase.

“I had not realized, before this last rereading,” Frye says in the preface to a 1962 reprint of Fearful Symmetry, “how completely the somewhat unusual form and structure of my commentary was derived from my absorption in the larger critical theory implicit in Blake’s view of art. Whatever importance the book may have, beyond its merits as a guide to Blake, it owes to its connection with the critical theories that I have ever since been trying to teach, both in Blake’s name and in my own.”16 Frye’s purpose in Fearful Symmetry is to study the relationship between Blake’s mature thought and the literary tradition. He assumes that Blake is best understood when the entire canon, from the early lyrics to the late and incomplete prophecies, is viewed as a unified achievement. The total vision is what is important. He assumes, furthermore, that the most enlightening kind of commentary on Blake will seek to place his work in its historical and cultural contexts (FS, 3–5). {52} By showing Blake’s relationship to the Western humanistic tradition, he intends “to establish Blake as a typical poet and his thinking as typically poetic thinking” (FS, 426). But placing Blake in this context does not mean locating the sources of his art in, say, the writings of Swedenborg or Plotinus; nor does it mean trying to uncover those events of history or of Blake’s personal life which seem to lie behind at least some of his poems. “In the study of Blake,” Frye argues, “it is the analogue that is important, not the source” (FS, 12). The study of these analogues turns out to constitute the bulk of Frye’s commentary, as he locates one Blakean parallel after another in the prose Edda, Chaucer, Spenser, Milton, the post-Augustans, the Ossian poems. Frye’s subject matter then is the speculative and symbolic aspects of Blake’s work and the relationship of both to the history of thought.

The starting point of his exegesis is not with individual poems but with Blake’s theory of knowledge; for it is only by understanding and then surrendering ourselves to the epistemological foundations of Blake’s thinking, Frye argues, that we can face squarely both the material and the pattern of his vision. Blake’s epistemology is that of a visionary, one who “creates, or dwells in, a higher spiritual world in which the objects of perception in this one have become transfigured and charged with a new intensity of symbolism” (FS, 8). Thus Frye devotes the first part of the book to placing Blake’s unitary theory of the imagination over against the separation of subject and object in the “cloven fiction” of Locke’s philosophizing. By following Blake’s own allegorical method and interpreting him in an imaginative rather than in a historical way, we are confronted with “the doctrine that all symbolism in all art and all religion is mutually intelligible among all men, and that there is such a thing as an iconography of the imagination” (FS, 420). The “grammar” of this iconography, or the way Blake represents his vision of reality by means of his special yet traditionally rooted symbolism, is what Frye charts in Fearful Symmetry. And he believes that by learning this grammar we can develop a key to the art of reading poetry. I n Anatomy of Criticism that part of the grammar which Frye learned from Blake appears chiefly in the Second and Third Essays.

The most important Blakean idea in the Second Essay has to do with the principles of simile and metaphor, Frye’s discussion of these coming at the end of his theory of symbols. In a system so firmly dependent upon the method of analogy as Frye’s, where argument progresses by associative leaps, we might expect to find frequent references to these two grammatical forms of association. Frye is not so much interested, however, in the rhetorical use of simile and metaphor as he is in the modes of thought which underlie them. These are analogy and identity, principles which represent the two processes by which the imaginative {53} power of the mind transforms the nonhuman world (Nature) into something with human shape and meaning (Culture). This is the point at which we begin to see the strong influence of Blake. In one of his autobiographical essays, Frye recounts the intuition that came to him as he was contemplating the fact that Milton and Blake were connected by their use of the Bible: “If [they] were alike on this point, that likeness merely concealed what was individual about each of them, so that in pursuing the likeness I was chasing a shadow and avoiding the substance. Around three in the morning a different kind of intuition hit me. . . . The two poets were connected by the same thing, and sameness leads to individual variety, just as likeness leads to monotony” (SM, 17). Blake opposed his own view of reality to the commonsense view of Locke, who conceived of subject and object as only accidentally related: the subjective center of perception exists at one pole; the objective world of things at the other. In order to classify objective things, one points to their resemblances. Thus Locke’s “natural” epistemology was based on the principles of separation and similarity. And the process of perceiving similarities, according to Blake, must always move from the concrete to the abstract. Thus in what Blake calls “Allegory” or “Similitude” we have a relationship of abstractions. Frye’s illustration of these Blakean terms is as follows:

The artist, contemplating the hero, searches in his memory for something that reminds him of the hero’s courage, and drags out a lion. But here we no longer have two real things: we have a correspondence of abstractions. The hero’s courage, not the hero himself, is what the lion symbolizes. And a lion which symbolizes an abstract quality is not a real but a heraldic lion. . . . Whenever we take our eye off the image we slip into abstractions, into regarding qualities, moral or intellectual, as more real than living things. (FS, 116–17)

Now what Blake opposes to the natural view of Locke, or to similitude in this sense, is the imaginative or visionary view of “Identity,” the literary form of which is metaphor.

The process of identity, according to Blake, “unites the theme and the illustration of it” (FS, 117). There are two kinds of identity perceived by the imagination. When Blake says a thing is identified as itself, he means to point not to its abstract quality but to its experienced reality. He calls this reality its “living form” or “image.” And all of Blake’s images and mythological figures, according to Frye, “are ‘minute particulars’ or individuals identified with their total forms.”17 In the second kind of identity things are seen as identical with each other. Here the Lockian view is turned upside down, since the perceiving {54} subject is now at the circumference and not the center of reality. All perceivers, since they are identical and not separate, are one perceiver, who, in Blake’s view, is totally human and totally divine. Blake’s image for this, in Frye’s words, is “the life of a single eternal and infinite God-Man,” in whose body all forms or images are identical.18 Thus, in the imaginative world of Blake, things are infinitely varied, because identified as themselves; at the same time, all things are of one essence, because identical with each other.

In the Anatomy Frye associates analogy with both descriptive meaning and realism, and identity with poetic meaning and myth, a separation based on Blake’s distinction between Locke’s natural epistemology and his own imaginative one. But the relationship as it is developed in the Anatomy is more complex than this. The conception one has of simile and metaphor depends upon the level of criticism he is engaged in, so that the meaning which metaphor has for a critic at the descriptive level will be different from its meaning at the anagogical.

At the descriptive level, metaphor and simile have the same function. To say “A is B” or “A is like B” is to say only that A is somehow comparable to B. “Descriptively,” as Frye says, “all metaphors are similies” (AC, 123). On the literal level, both metaphor and simile are distinguished by the absence of a predicate. A and B are simply juxtaposed with no connecting link, as in imagistic poetry. “Predication,” Frye says, “belongs to assertion and descriptive meaning, not to the literal structure of poetry” (AC, 123). At the formal level, where images are the content of nature, metaphors and similes are analogies of natural proposition, thus requiring four terms, two of which have some common factor. Thus “A is B” or “A is like B” means at the formal level that A:X::B:Y, where the common factor is an attribute of B and Y. “The hero was a lion” is Frye’s example, and we recognize in this illustration that formal metaphor is close to what Blake meant by the abstract similitude. In the archetypal phase, the metaphor “unites two individual images, each of which is a specific representative of a class or genus” (AC, 124). Dante’s rose and Yeats’s rose, while symbolizing different things, nevertheless represent all poetic roses. Archetypal metaphor is thus related to the concrete universal, and its Blakean analogue is the first kind of identity, identification as. Finally, at the anagogic level the most important analogical principle is metaphor in its radical form. To say that “A is B” means not that they are uniform or that they are separate and similar but that they are unified. Since literature at this level is seen in its totality, everything is potentially identical with everything else. This, of course, corresponds to Blake’s second kind of identity, identity with.

“A work of literary art,” Frye says, “owes its unity to this process of {55} identification with, and its variety, clarity, and intensity to identification as” (AC, 123). His own interests direct him most often to search out the former of these analogies. The world of mythology lies at the center of his predilections, and this is the world of implicit metaphorical identity: to speak of a sun-god in mythology is to say that a divine being in human shape is identified with an aspect of physical nature. On the other hand, the world of realism, which lies at the periphery of Frye’s own interests, is the world of implicit simile. To say that something is “lifelike” is to comment on its “realism,” a term Frye once referred to as that “little masterpiece of question-begging” (FS, 420). So important is the principle of identity to Frye that he sometimes quite explicitly uses it to distinguish poetry from discursive thought or to define the formal principle of poetry.19

Analogy and identity, then, are the two important concepts by which nature and human forms are assimilated. Analogy and simile establish the similarities between human life and nature, whereas identity and metaphor show us an imaginative world where things attain a human, rather than merely a natural, form. “If we ask what the human forms of things are,” says Frye, “we have only to look at what man tries to do with them. Man tries to build cities out of stones, and to develop farms and gardens out of plants; hence the city and the garden are the human forms of the mineral and vegetable world respectively.”20 We will see how Frye applies the principle of radical metaphoric identification when we come to the Third Essay. At this point it is important for us to recognize that the radical form of metaphor “comes into its own,” as Frye says, in the anagogic phase. Both anagogy and radical metaphor, as principles of literature at the highest imaginative level, show us a poetic world completely possessed by the human mind.

Apocalyptic reality is for Frye, as it was for Blake, reality in its highest form. It is what the human imagination can conceive at the extreme limits of desire. Frye’s conception of apocalypse is based upon a radical disjunction between the phenomenal and noumenal worlds, between what is perceived by sensory perception and what is apprehended by the reach of imagination, or between the “fallen” and “unfallen” worlds. Apocalypse is synonymous with the latter of these categories, and it has been represented variously as the Revelation at the end of the Bible or the Paradise at the beginning, to use the Christian metaphors; or as the Golden Age, to use the image of classical antiquity. It is only in the apocalyptic world, according to Frye, that nature can be humanized and man liberated—and both are achieved at the same time by the principle of radical metaphor. “This is apocalypse,” says Frye, “the complete transformation of both nature and human nature into the same form.”21

{56} It took Frye twenty years to articulate the contrast between similarity and identity, which he calls “one of the most difficult problems in critical theory” (CP, 23). Identity is clearly a principle of literary structure for him, and in a number of places he has described the various forms which the drive toward identity takes. But in his later writings Frye has been more intent on making clear that the drive toward identity is a process engaged in by readers as well as by literary characters. There are recognition and self-recognition scenes in life as well as in literature. The latter, Frye says, have much to do in helping us in the journey toward our own identity. In The Secular Scripture he speaks of the highest form of self-identity as coming from one’s vision of the apocalyptic world, the original world from which man has fallen, a world of revelation and full knowledge which exists mysteriously between “is” and “is not” and in which divine and human creativity are merged into one.22 In such a state, the distinction between subject and object disappears in favor of a unified consciousness. In poetry, identity-with, as opposed to identity-as, means that the poet and his theme become one. The religious analogue of such a relation is the symbolic act of communion. Another analogue is the relation between lovers, who, like poets, identify themselves with what they make. Frye says that artists like Beckett and Proust

look behind the surface of the ego, behind voluntary to involuntary memory, behind will and desire to conscious perception. As soon as the subjective motion picture disappears, the objective one disappears too, and we have recurring contacts between a particular moment and a particular object, as in the epiphanies of the madeleine and the phrase in Vinteuil’s music. Here the object, stripped of the habitual and expected response, appears in all the enchanted glow of uniqueness, and the relation of the moment to such an object is a relation of identity. Such a relation, achieved between two human beings, would be love. . . . In the relation of identity, consciousness has triumphed over time. (CL, 220)

For Frye, such a relation is the singular way of regaining, in literature and life, that apocalyptic vision of the paradise which has been lost.

The Phases of Symbolism Synthesized

What purpose, finally, is served by Frye’s analysis of the phases of symbolism? This question should be seen in the context of Frye’s aim, which is to argue that a finite number of valid critical emphases can all be synthesized into one system. Thus he is led to maintain, to take one {57} example, that historical scholarship and the New Criticism should be seen as complementary, not antithetical, approaches. Frye’s attempt to synthesize these and other legitimate methods into a broad theory of contexts means that his attention is always directed away from the peculiar aims and powers of a given critical method. And even though the differences among approaches provide the basis for his classifying in the first place, these differences are always related to a single category or set of concepts, the most important in this essay being symbol, narrative, and meaning. In other words, Frye translates the principles of other methods into the language of his own discourse; and this, along with the breadth of reference of his special categories, expanded far beyond the particular meaning they have in Aristotle, greatly facilitates his achievement of the synthetic end.

The question then becomes: What function is served by the synthesis? A part of Frye’s answer is found in his discussion of the formal phase where he claims that knowledge of the “whole range of possible commentary” will help “correct the perspective both of the medieval and Renaissance critics who assumed that all major poetry should be treated as far as possible as continuous allegory, and of the modern ones who maintain that poetry is essentially anti-allegorical and paradoxical” (AC, 92). In other words, there is no need for the critic to restrict himself to one approach.23 “The present book,” Frye says in the “Tentative Conclusion,” “is not designed to suggest a new program for critics, but a new perspective on their existing programs, which in themselves are valid enough. The book attacks no methods of criticism, once that subject has been defined: what it attacks are the barriers between the methods. These barriers tend to make a critic confine himself to a single method of criticism, which is unnecessary, and they tend to make him establish his primary contacts, not with other critics, but with subjects outside criticism” (AC, 341).

Frye’s theory of phases, however, has a function beyond that simply of universalizing the critical perspective and thus serving to lessen critical differences. As we move up the critical ladder to the last two phases, we arrive finally at that kind of criticism upon which the unification of critical thought depends. “In this process of breaking down barriers,” says Frye, “I think archetypal criticism has a central role, and I have given it a prominent place” (AC, 341). Thus Frye’s theory of phases serves to indicate where he himself stands as a critic. His conception of the archetype is absolutely central to his entire theory, not only because it is a steppingstone to the ultimate critical enterprise of the anagogic phase, but also because it is the basis for his theories of myth and genre. The first of these is archetypal criticism itself.

Notes

1. {237} AC, 72. Frye equates pluralism here with relativism. And yet, although pluralism would also affirm that there is a finite number of valid critical methods, it would certainly deny that they can all be contained in a single theory. Pluralism and relativism need not be the same thing. Even if there are several valid critical methods, it does not necessarily follow that they can be, or even need to be, contained within a single theory. But Frye’s synoptic goal and his approach to the problem of meaning require that he attempt to include in one theoretical scheme all the different methods found in the history of criticism and the theories of meaning they produce.

2. AC, 82. Frye’s account of literal meaning derives in particular from Richards, Blackmur, Empson, Brooks, and Ransom; see AC, 358. The conception of mythos and dianoia assumed by the literal phase figures importantly in the Fourth Essay of the Anatomy.

3. See The Languages of Criticism and the Structure of Poetry, pp. 100–102.

4. It can be argued that in attempting to refute the logical positivists Frye has let his opposition dictate the terms of his argument. Meyer Abrams makes the same point {238} with regard to Philip Wheelwright’s The Burning Fountain (“The Newer Criticism: Prisoner of Logical Positivism?” Kenyon Review 17 [1955]: 139–43). An opposing assessment of Frye’s position on this issue has been stated, though not argued, by Walter Sutton: “By asserting in his discussion of the descriptive and literal phases that the literary symbol has both outward, or centrifugal, and inward, or centripetal, meaning—that it functions both as a sign and as a motif—Professor Frye avoids the referential-syntactical dilemma that has plagued modern contextualist criticism since the formulation, in the mid-Twenties, of I.A. Richards’ distinction between the emotive pseudo-statements of poetry and the referential language of science” (Symposium 12 [1958]: 212). Homer Goldberg, on the other hand, has argued that the New Critical assumptions about discourse underlie not simply Frye’s discussion of the first two phases but the entire Second Essay (“Center and Periphery: Implications of Frye’s ‘Order of Words.’ ” Paper read at the Modern Language Association Meeting, 27 December 1971, pp. 3–6. Photoduplicated copy). On Frye’s relationship to the New Criticism, see also Robert Weimann, “Northrop Frye und das Ende des New Criticism,” Sinn und Form 17 (1965): 621–30; Pierre Dommergues, “Northrop Frye et le critique americaine,” Le Monde (Supplement au numero 7086), 25 Octobre 1967, pp. iv–v; Richard Poirier, “What Is English Studies, and If You Know What That Is, What Is English Literature?” Partisan Review 37 (1970): 52–53; Monroe K. Spears, “The Newer Criticism,” Shenandoah 21 (1970): 110–37; Edward Wasiolek, “Wanted: A New Contextualism,” Critical Inquiry 1 (March 1975): 623–29. In The Critical Path, Frye remarks that the great value of the New Criticism “was that it accepted poetic language and form as the basis for poetic meaning” and thus resisted all forms of determinism. “At the same time, it deprived itself of the great strength of documentary criticism: the sense of context. It simply explicated one poem after another, paying little attention to genre or any larger structural principles connecting the different works explicated” (CP, 20).

5. Freistimmige, a term Frye borrows from music, refers to the pseudocontrapuntal style where strict adherence to a given number of parts is abandoned, voices being free to enter and drop out at will.

6. AC, 89, 91. See also Frye’s article on “Allegory” in Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, ed. Alex Preminger (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1965), pp. 12–15. On “commentary,” see also his essay “Literary Criticism,” in The Aims and Methods of Scholarship in Modern Languages and Literatures, ed. James Thorpe (New York: Modern Language Association, 1963), pp. 65–66.

7. Perhaps as much as any other contemporary critic, Frye has tried to collapse the distinction between high and low culture, between sophisticated and naive forms of art. This is one of the chief reasons for his wanting to remove value judgments from the proper scope of criticism. For Frye’s ideas on popular literature, see The Secular Scripture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1976), pp. 21–29. Hereafter cited as SeS.

8. Frye uses the word “ritual” more or less conventionally. “Dream,” however, as evident from our discussion already, refers not simply to the subconscious activities of sleep but to the entire interrelationship between desire and repugnance in shaping thought. See AC, 359. For a more extensive discussion of ritual as a socially symbolic act, see SeS, 55–58.

9. See also A Natural Perspective (New York: Columbia University Press, 1965), p. 73, hereafter cited as NP; and Theodore Gaster’s notes to The Golden Bough (New York: Criterion Books, 1959), pp. 391–92.

10. “Three Meanings of Symbolism,” Yale French Studies, no. 9 (1952), p. 18.

11. Quoted and endorsed as aptly characterizing Frye’s definition of the anagogic symbol by Walter Sutton, Modern American Criticism (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1963), p. 255. See also Warren Shibles, “Northrop Frye on Metaphor,” in An {239} Analysis of Metaphor in Light of W.M. Urban’s Theories (The Hague: Mouton, 1971), pp. 145–50.