By Stephen Surlin

Systemic marginalization of communities of colour and the mirroring of this marginalization in online and digital spaces is a problem for civic engagement and more generally democratic process. My research seeks to use a Critical Race and Technology theoretical lens to explore how the collective creation and moderation of Local Area Networks (LAN) can promote democratic decision making in the creation of digital archives and participation in knowledge sharing around a community garden, primarily involving seniors of colour in the downtown Ward 3 of Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. I will use methodologies of relational art in order to promote community collaboration and increased civic engagement, rather than a top-down model of interactive art.

Digital Heirlooms: Familial Digital Archives, Data sovereignty and the Physical Location of Data

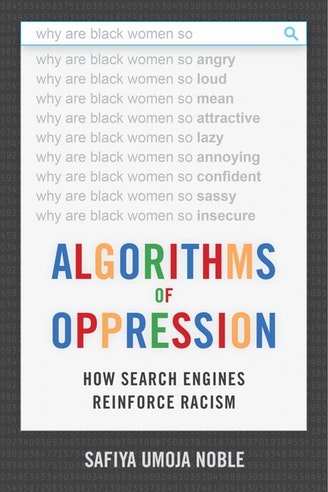

The focus on localized, place based LAN networks is to subvert the current dominant forms of networked multi-media archiving that often involves corporate (for profit) run platforms that are sustained by global click-through rates (internet traffic), used to generate ad revenue and the collecting of, often anonymized, user data that can be used as a commodity in the information economy. The page ranking system behind the Google search engine uses an algorithm that lead to the most relevant, and often most profitable, search result to be at the top of the list. Safiya Umoja Noble, a leading academic in the field of critical race and technology, emphasizes the significant role of search algorithms’ cultural and racial co-optation when observing the search results of the Google search engine, which prioritizes search results that represent women, particularly Black women codified as “girls”, to be ranked in search results in ways that underscore their relatively low status in society (Noble 2013). These algorithms are often superficially experienced, presented and understood as a “neutral” or “objective” decision making tool, as Safiya Noble outlines in her book, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (Noble, 2018). Noble considers this neutral position to be one of the primary ways that previous systems of oppression are able to continue, e.g. racism, sexism, without holding accountable the people involved in the making of these information platforms and “decision-making tools” tools. This method of scientific/mathematic separation of people into categories for the benefit of groups in power, is a tactic used during the Enlightenment and modern era in order to control and separate people of colour from Eurocentric or White culture in order to maintain dominance (Noble, 2013).

The need for increased civic engagement and public discourse can be traced back to the beginnings of liberal philosophy and Western cultures’ shift from feudalism to market based economics and democracy in Europe. Hannah Arendt contextualizes the way liberalism developed during the age of Enlightenment, through her book, Lectures on Kant’s Political Philosophy (1992). These writings on Emanuel Kant’s political philosophy analyze the way liberalism, ushered in by the “bourgeois public sphere”, paved the way for the increased role of “publicity”. Kant’s theory is based in the idea that the “very faculty of thinking depends on its public use” and that without “free and open examination,” it is not possible to form ideas, suggesting that reason cannot be made in isolation, but in “community with others” (Arenddt, 1992). Arendt expands on this idea, stating that, “the external power which deprives man of the freedom to communicate his thoughts publicly also takes away his freedom to think” (Arenddt, 1992).

By circumventing these commercial platforms, communities of colour can create digital archives that are organized by the community, rather than commercial interests. These archives can provide the opportunity to develop a unique form of “publicity” that can leverage the place-based data sovereignty of a LAN. This sovereignty becomes more significant when a community is archiving their familial histories using digital tools, including images, video, audio recording, text, 3D Scans and biometric data. These forms of new media archiving often requires several gigabytes, sometimes terabytes, of storage, leading to the reliance on cloud-based storage systems like Google Drive. The use of cloud services like this leave the user susceptible to the law of foreign governments like the United States of America that can use government policies to have access to your data, potentially infringing on the community’s ownership over their histories or intellectual property. A marginalized communities’ ability to access digital archiving tools may be linked to publicly funded institutions like libraries (that are susceptible to defunding) or through the use of smartphones and home computing, that often lead to increased use of commercial information sharing platforms. This increased reliance on these commercial platforms, often framed as a “digital divide” follows racial lines that can be traced back to institutional systems of racial marginalization like the practice of “red lining” in the United States of America.

Digital Divisions Along Racial Lines: The Legacies of Marginalized Communities’ experience in the Built Environment and Online Spaces

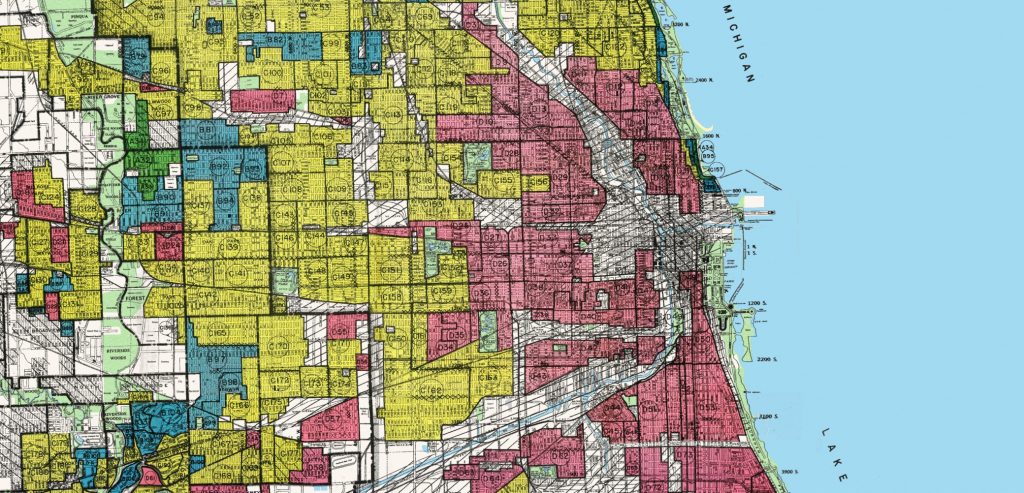

Geographic marginalization as experienced by Black American citizens following the abolishment of slavery separated them from being integrated into the dominant groups’ communities, leading them to live in areas that afford equal opportunity to jobs, safe and adequate housing, and the capital needed to own land or housing access to social networks that lead to increased economic wealth in industrial or corporate environments of Northern US cities like Chicago, Illinois, that appear to promise the new freedoms afforded to recently freed African-American slaves following the abolishment of slavery in the US. The process of separating Blacks from the White communities of Chicago was done using a method called “redlining”, an institutionalized system of assessment of property value and potential future investment risk that lead to neighbourhoods being measured in terms of risk: green/blue is low, yellow is medium, and red is high. The red high-risk designation, often attributed to Black communities, is what lead to the term “redlining” and stopped Black citizens and families from moving into non-ghettoized communities. Residents of redlined neighbourhoods were often stuck in a predatory financing system, due to “contract buying”, a practice that later became illegal, as discussed by Ta-Nehisi Coates in the chapter of his book titled, “The Case for Reparations” (2017). The history of redlining has since resulted in a continuation of the practice through economic imperatives around telecommunications infrastructure and the navigation of online spaces.

Lisa Nakamura asks us to challenge assumptions around the way engagement with the internet and network communications may skew ideas around what that access means for marginalized users. In Digitizing Race: Visual Cultures of The Internet (2008), Nakamura argues that while it is widely accepted that media interactivity is power, suggesting scholars and institutions have an interest in measuring types and degrees of digital interactivity among different social groups, along with a need to asses power differentials between people of color, youth, senior citizens, and others to deploy their identities on the internet (Nakamura 2008, 176). Internet and networked communication can lead to a continuation of entrenched socio-economic oppression and deepen cultural and economic divides, though, with increased engagement with systems that increase diverse methods for the construction and expression of identity, while providing the opportunity for increased civic engagement.

Relational Art and Methodologies of Shared Authorship in the Creation of Culture

Relational art, relational aesthetics and participatory art are forms of cultural production that use production methods that result in varying degrees of distributed authorship, collaboration and profit models that often involve facilitators and participants in collaboration. Elizabeth Miller, et al. provide a sufficient definition for the kind of methods in intend to use for my research in their book, Going Public: The Art of Participatory Practice (2017):

Participatory projects stem from a desire to challenge the power relations that play out in mainstream media projects. Who speaks for whom is a central concern, and more accessible media tools and platforms have fostered opportunities for first-person and multi-vocal narratives to challenge the authority of a single author or a closed narrative. An opportunity to disrupt the traditional hierarchies of media practices and to foster more democratic exchanges is part of the lure and excitement around emergent media platforms and practices. By opening up authorship and opportunities for user engagement, we place more emphasis on the process than on a finished piece or singular text

(Miller, et. al 2017).

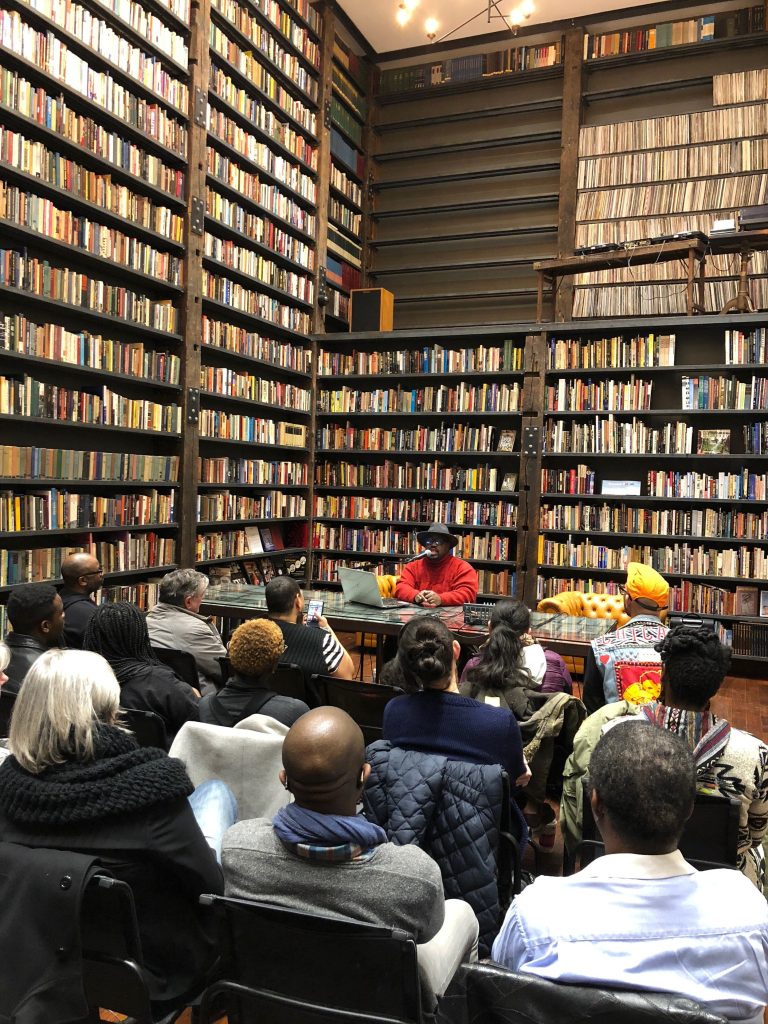

Theaster Gates is a Chicago, Illinois based multidisciplinary artist working in sculpture, clay, tar, and found objects from dilapidated and soon to be demolished buildings and archives. Gates works as an urban planner within the South side of Chicago to develop neighbourhoods infrastructure with his not-for profit organization Rebuild Foundation. This organization runs the Stony Island Arts Bank, Black Cinema House, Dorchester Art and Housing Collaborative, Archive House, and Listening House. These amenities provide opportunities for the residents of South Side Chicago, to engage in the production and consumption of information that is generated by and with the community, along with multimedia archives that would otherwise be lost, e.g. A large collection of Jet and Ebony magazines and several large record collections, all of which were heading to the garbage dump but were given a space to be preserved and observed. These books, magazines and records also make up largely influential forms of cultural communication that American Black populations had access to in the history of African-American identity construction since the end of slavery in North America. The creation of these multiple archives then acts as spaces that can circumvent and subvert commercial information systems that may profit from the co-opting of Black identity (Noble 2013, Noble 2018)

Along with tours of the collections and archives housed in the Stony Island Arts Bank, the public can attend a series of events and workshops that are held at the space, including: writing workshops, entrepreneurial courses, and free family portraits to highlight the diversity of the neighbourhood and its families (Rebuild Foundation, 2019). Gates and the Rebuild Foundation is an example of how the creation and access to archives that are rooted in a community of can inform the history or culture of a community can improve the ability for the community to construct and communicate past and future forms of identity, with increased complexity.

The Democratic Community Garden: MediaWiki Archiving and Content Moderation

I intend to engage in research creation methods to produce a model for further implementation of the research methods I develop. Using the previously mentioned theoretical frameworks, my project may involve the following elements:

- Work with a local cultural organization to begin creating collective archives and to promote the project in order to get volunteers for collaborative projects

- Look at options for the creation or joining of existing community garden organizations in order to gain access to a garden plot that can be democratically managed by the community group, e.g. Powell Park Community Garden in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

- Continue development of a mobile server that can be embedded in the garden that can house open-source server software, preferably MediaWiki, in order to create a digital multi-media archive that is populated with content by the community and moderated by a democratic committee

This research will take the form of a relational art project, since the archive can exist, not only as an institutional system of documentary, but as a source for the recording of oral histories, stories, recipes, art works, songs and other forms of cultural expression. A relational art methodology in this context also provides examples for the shared authorship and collaborative ethos of collective archive production.

The location of the MediaWiki server in a public place, and the use of a LAN to access the MediaWiki is a strategy that seeks to subvert the reliance on commercial Internet Service Providers (ISP) and for profit knowledge/media sharing platforms that can co-opt cultural identity, as discussed by Noble, and reduce data sovereignty by having greater control over the communities’ data, rather than having it be surveilled and made susceptible to corporate or government organizations. The use of LAN and community moderation is also intended to lower the exposure of the local community organization involved in the garden to forms of online bullying and forms of abusive content or hate speech, since the moderating of this kind of content is a big part of social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter. In, Cybertypes: race, ethnicity, and identity on the Internet (2002), Nakamura outlines the ways policing, often by users along with the platforms moderators, in spaces like online gaming and chat spaces, preserves the default “whiteness” of online identity/personae present in these spaces that ultimately helps to eradicate “otherness” (Nakamura 2002, 4). This emphasizes the need for culturally sensitive and place-based content moderation. In Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions That Shape Social Media (2018), Tarelton Gillespie outlines the socio-cultural dynamics of content moderation in networked spaces, stating that content moderation is, “an enormous part of the work of running a platform, in terms of people, time, and cost” (Gillespie, 2018). Gillespie elaborates on platforms’ effect communities that are often coded as “other” to the teams that create them:

Social media platforms may present themselves as universal services suited to everyone, but when rules of propriety are crafted by small teams of people that share a particular worldview, they aren’t always well suited to those with different experiences, cultures, or value systems.

(Gillespie, 2018)

Gillespie goes on to emphasize the need for communities to develop forms of government that match the values and needs of the community in regard to content management:

These champions of online communities quickly discovered that communities need care: they had to address the challenges of harm and offense, and develop forms of governance that protected their community and embodied democratic procedures that matched their values and the values of their users.

(Gillespie, 2018)

My research into the shared creation of these digital archives using MediaWiki will question the effects and boundaries of open-source licensing and the various levels of shared authorship and nuanced intellectual property designations, forfeitures of ownership and future use stipulations found in GNU GPL (General Public Licence), Copyleft and MIT License. MediaWiki uses a “Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License” (creativecommons.org, 2019) that considers you free to:

- Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format

- Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially.

Under the following terms:

- Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

- ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original.

- No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits.

The sharing of personal archival materials in multiple mediums may lead to the need to be able to decide how content can exist on the archive and all following forms of the content.

The organizing structure of a community garden and the familiar forms of the sharing of local stories, histories and knowledge is intended to leverage the familiar systems of trust and collaborative dialogue found in these spaces. This trust system and collective content moderation can promote civic engagement and position community members, especially seniors of colour as experts and knowledge bearers that can also promote intergenerational knowledge transfer and place-based localized multi-modal archiving and knowledge sharing.

Citations

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. 2017. We Were Eight Years in Power: an American Tragedy. One World Publishing, Chapter 6: “The Case for Reparations.”

Creative Commons. 2019. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

Digital Scholarship Lab. “Mapping Inequality.” Digital Scholarship Lab, dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/.

Gillespie, Tarleton. 2018. Cybertypes: race, ethnicity, and identity on the Internet. Yale University Press.

Miller, E., Little, E., High, S. 2017. Going Public: The Art of Participatory Practice. UBC Press.

Nakamura, Lisa. 2008. Digitizing Race: Visual Cultures of The Internet. University of Minnesota Press:95-130, Chapter 3: “The Social Optics of Race and Networked Interfaces in The Matrix Trilogy and Minority Report.”

Noble, Safiya U. 2013. “Google Search: Hyper-Visibility as a Means of Rendering Black Women and Girls Invisible.” Invisible Culture, no. 19:1-31.

Noble, Safiya U. 2018. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York University Press.

Rebuild Foundation. 2019. Rebuild-foundation.org. https://rebuild-foundation.org/site/stony-island-arts-bank/.

Leave a Reply