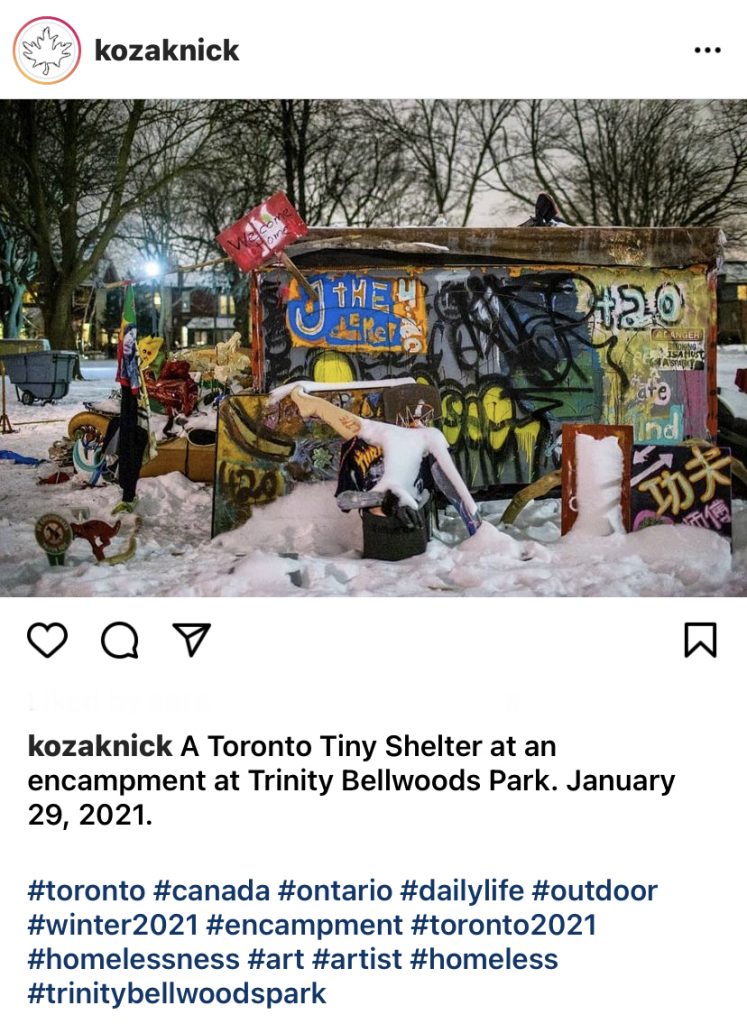

The city of Toronto, Ontario encompasses a span of little homes, shacks, and encampments; a population of unique identities that struggle every day to fight the structures of erasure that are trying to displace them physically over time. These shelters are more than just structures, they are a part of an initiative by the Toronto Tiny Shelters Organization to raise awareness and support for the homelessness crisis in Toronto.

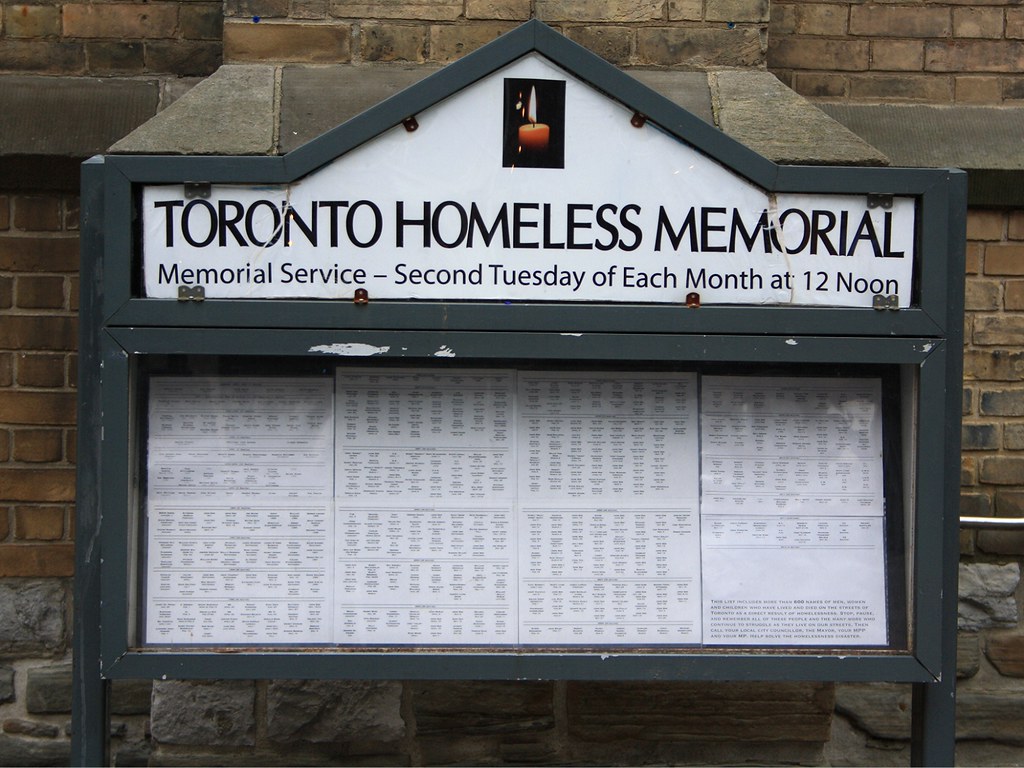

The organization was formed by Khaleel Sievwright, a former carpenter, aged 28 who built his first shelter for himself while he was homeless living outside in -15 degree B.C weather. Sievwright has been concerned with the homelessness crisis in Toronto especially experiencing it himself. Building the shelters is something he states “[he] already knew how to do”, so he began to use his skills to help others like him. He makes these structures with the accompaniment of his team and a community of willing volunteers. As temperatures drop below -20 degrees Celsius and the numbers spike in COVID-19 related deaths, the homelessness crisis grows far more dangerous as it consumes more lives. This year, the homelessness crisis has contributed to the displacement of over 10,000 residents all over the city of Toronto. As Sievwright and his team strive to build more shelters, stricter regulations are placed by the City of Toronto to remove them.

An injunction filed against Khaleel by the City on February 12th prevents Sievwright from making, repairing, or relocating these tiny shelters on any land that is classified as city-owned. The structures are counting at 300, and Sievwrightexpressed that he started building the shelters to safeguard a population of people he regards as “the most vulnerable”. The shelters he builds are a small part of a temporary solution to keep people alive until they can access alternative housing. With the very brutal winter approaching, the death rate in Toronto will skyrocket. This injunction works to perpetuate the uprootedness of the homeless population by placing restrictions on the claiming of space necessary for survival.

The trail of homes and tents are not hard to miss, as they are situated in several places throughout the city. Looking at the issue of homelessness in Toronto points to a broader structure of poverty and environmental racism present within Canadian institutions. Not only has this structure been perpetuated by the historical upliftment of whiteness in Canada but it is further emboldened by the Anthropocene, an age termed by Paul Crutzen. Specifically, the lens of the Anthropocene reveals how the intensification of climate change amidst the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately impacts minority peoples. The persistent elimination of initiatives such as these tiny shelters further reveals how governing systems in Canada are working “against efforts to sustain livable climates and the abilities of people to adapt”. When examining the origin of the Anthropocene it becomes clearer how this structure of uprootedness is established off a colonial framework and hierarchal structure, that works subtly to displace racial minorities by preventing them from establishing settlement on the land.

The Anthropocene, like the etymology of geography, describes the literal writing of the earth’s geography. Heather Davis and Zoe Todd argue that the start of the Anthropocene should be 1610, coinciding with the early colonial exchanges of goods, crops, and animals which contributed to the drastic shift in the landscape. This further contributed to the displacement of early Indigenous nations and the unequal power relationships between different groups of people. Land in North America has historically been a composite for the removal of those who oppose the structure of whiteness or those that are differently invoking initiatives of climate correction that have radically impacted the biosphere and promote “the right way of living”. Sievwright is an example of this, as he works to establish sustainable housing in ways that the governmental structure seems to oppose. The issue of homelessness persists within minority communities not just as a social issue, but as an uprootedness that is present in society as a whole and how it removes minorities from settling in public spaces. For example, African Americans are 16 times more likely to end up in shelters than their white counterparts. The issue of homelessness speaks to the greater more pertinent structure of poverty present in black neighborhoods and their poor sustainment amidst environmental destruction. The African American population comprises 26% of those living in poverty and 40% of the homeless population. Black men specifically are also more likely to find themselves in shelters, where they remain longer than white men. These statistics only depict one demographic amidst the many that exist.

On March 19,2021, the city of Toronto posted a notice evicting all encampments in parks across Toronto. Not only will this displace several homeless people, but it renders them homeless until the city determines a suitable shelter for them indoors, one that is unlikely with the overcrowded shelter system. Sievwright’s structures reclaim shelter and survival for many who are subjected to a harsher reality. Sievwright calls on the help of the public through a Go Fund Me page where he wants to raise more money for building materials. The shelters are not only a physical manifestation of settlement and rootedness but a message that works to enforce the resettlement of lands that have been owned by structures of colonialism. It describes “not merely the ‘human impact’ on the nonhuman world but also the folding of human activity into earth-surface systems such that it becomes in some sense indigenous to those systems”. Human activity is linked to space and land. Sievwright’s story is a testament to how land has historically been placed in the hands of those that hinder the navigation and livelihoods of vulnerable populations to the point where even initiatives that serve to fix it are disbanded.