By: Elizabeth Ball

We are currently living in a geological age known as the Anthropocene. The Anthropocene is characterized by losses due to human-induced negative impacts on the environment such as losses of ecosystems, lands, and species. Some of these losses have already occurred, while some are happening now and will result in lost futures. One species that is suffering loss at an alarming rate is the pangolin. The pangolin is considered the most trafficked non-human mammal in the world for its scales and other body parts. Despite this fact, many people are still unaware of its existence and its ecological importance.

Humans began decimating the pangolin population over a decade ago and the loss is becoming increasingly worse despite laws and protections in place. Currently, all eight species of pangolin are under the threat of extinction due to human industries threatening their futures. These industries include illegal trading, trafficking, poaching, and deforestation causing loss of their natural habitats. The estimated number of pangolins alive in the wild is unknown because of illegal trading.

The pangolin is the only mammal with scales; it does not have many predators in the wild as its scales act as armour. The scales of a pangolin are made of keratin and are essentially impenetrable. Predators in the wild that are a threat to pangolins include lions, tigers, leopards, hyenas, and pythons. However, life-threatening human-pangolin relations are the only threat to the overall pangolin population. If a pangolin is threatened in the wild, it will curl into a ball and use its scales to defend itself and also release a foul odour; however these actions do not protect it from being hunted down by poachers with their dogs.

Illegal poaching is occurring in Asia and Africa where pangolin lives are being treated as a commodity for human consumption. Pangolins are killed for their meat which is considered a delicacy in some Asian countries, their scales made of keratin, their fetuses, and their blood. Their scales are used in traditional medicine and are believed to help with lactation issues, skin conditions, and inflammatory illnesses, while their blood is used as a healing tonic. However, there is no scientific evidence for any of this. According to the UN Environment Programme website, “In September 2018, customs officials in Viet Nam seized 805 kg of pangolin scales hidden inside dozens of boxes on a flight from Nigeria . . . The pangolin trade is banned in Viet Nam. But weak law enforcement has allowed a black market to flourish and feed into a global multibillion-dollar industry in animal parts, mainly for traditional Chinese medicine and exotic pets.”

There are four species of pangolin that live in Africa and four that live in Asia. The pangolin feeds on termites and ants, playing the role of pest controller and keeping balance in its ecosystem. Because of this role, “pangolins are known as the guardians of the forest . . .” For example, as stated on Born Free USA, “Pangolins have an extremely important ecological role of regulating insect populations. One single pangolin can consume around 70 million ants and termites per year. If pangolins go extinct, there would be a cascading impact on the environment.”

Through balancing the ecosystem in which it lives, the pangolin also plays a role in multi-species relations and co-development. In Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s work, The Mushroom at the End of the World, she quotes biologist Scott Gilbert and his colleagues who write, “Almost all development may be codevelopment,” (142) which can be applied here to the relationships pangolins have within the environments they inhabit. For example, they help tend the soil by aerating it when searching for insects which “improves the nutrient quality of the soil and aids the decomposition cycle, providing a healthy substrate for lush vegetation to grow from. When abandoned, their underground burrows also provide habitat for other animals.”

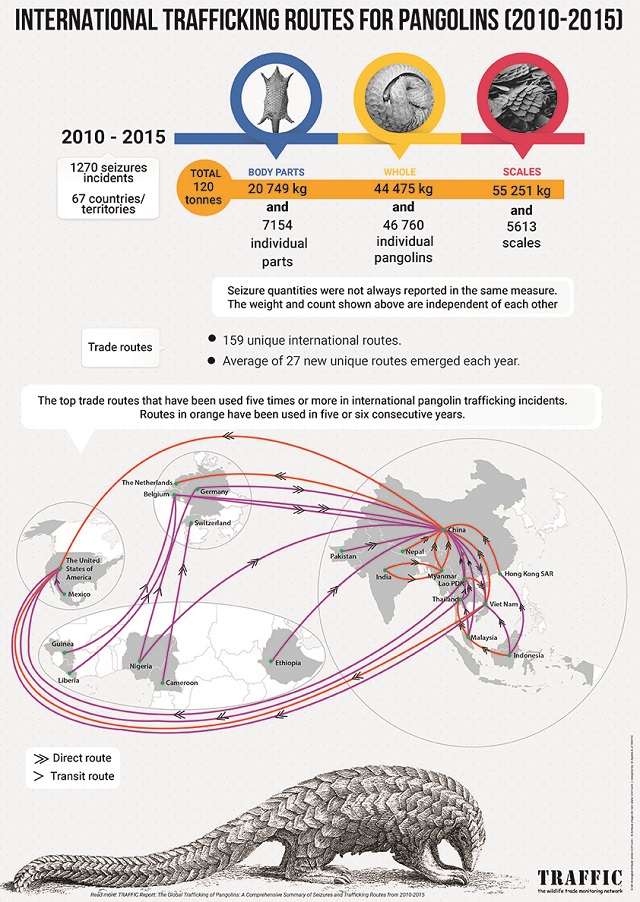

There is a species hierarchy in place between humans and pangolins where humans are dominating over the pangolin species. Thom van Dooren speaks to this type of power structure in his chapter, “Mourning Crows: Grief in a Shared World,” where he addresses what he calls “human exceptionalism” and states that this exceptionalism is “what holds us distant, intellectually and emotionally, from our more-than-human world” (126). The pangolin is at the point of critical endangerment through being trafficked like a commodity. Hunting, poaching, and trading the pangolin species are examples of human exceptionalism. The image below shows the international trafficking routes for pangolins between 2010 and 2015. These numbers continue to grow as “more than 1 million pangolins were trafficked over a ten-year period, though this number may be conservative given the volume of recent pangolin scale seizures. An estimated 195,000 pangolins were trafficked in 2019 for their scales alone, according to Challender, et.al (2020).” Although the majority of trafficking occurs in Africa and Asia, it is an international problem.

With humans being the major threat to the pangolin population, humans are also needed to prevent their future from being lost. All eight pangolin species are now protected under international law, and there are organizations such as The Tikki Hywood Foundation which work to rescue, rehabilitate, and release pangolins back into the wild. The YouTube video on the Pangolin Men in Zimbabwe is an example of the work being done to help save pangolin futures. The video shows their innocence and provides hope that there will not be a lost future for this humble animal through the life saving human-pangolin relationships at work.

World Pangolin Day occurs on the third Saturday of February every year and is a way to draw awareness to the importance of the pangolin and the struggles the species is enduring. We as humans must acknowledge the codependency between humans and pangolins – that humans need the help of pangolins to keep a balanced ecosystem and that pangolins are now in need of help from humans to survive. It is important to protect pangolin environments as “when we preserve pangolin habitats, we not only preserve pangolins, we preserve that habitat for all resident species.” Thom van Dooren considers “the general lack of popular interest in the deaths of species . . .” as “a failure to appreciate all the ways in which we are at stake in one another, all the ways in which we share a world. This failure is, at least in part, rooted in . . . human exceptionalism” (140). Human and nonhuman species are all connected and we must do our part to understand, educate, and advocate for species like the pangolin in order to protect their futures and prevent further loss in the Anthropocene.

Works Cited

Grein, Giavanna. “The Fight to Stop Pangolin Extinction.” WWF. Accessed 26 February 2021. Web.

Moreno, Adam. “Pangolin Conservation.” Creature Conserve. June 2020. Web.

“Pangolins.” Born Free USA. Accessed 26 February 2021. Web.

“Pangolins: Natural Pest Controllers and Soil Caretakers.” worldpangolinday.org. Accessed 17 March 2021. Web.

“Saving Pangolins: The Guardians of the Forest.” The Nature Conservancy. Accessed 26 February 2021. Web.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. “Interlude: Tracking.” The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (2015): 137-144. Print.

Van Dooren, Thom. “Mourning Crows: Grief in a Shared World.” Flight Ways: Life and Loss at the Edge of Extinction (2014): 125-144. Print.

“Zimbabwe pangolin project working to save world’s most trafficked animal.” UN Environment Programme. 15 February 2019. Web.