On a small dirt road that marks the boundary between Canada and the United States, a makeshift wigwam stands. In the middle of the night, over a year ago, accompanied by a dozen or so friends, Geraldine McManus drove her white camper van down the path and set up camp close to the small hamlet of Gretna. According to local lore, the area was once known as “Smuggler’s Point” because fur trappers and early settlers used to run undeclared goods over the border. From McManus’ base you could see the outline of the buildings that make today’s official ‘port of entry’, where customs officers regulate the migration of goods and people.

But, where she stood, nothing was stopping her from taking the few steps that would take her to another country. No fence, no border. Just a single white marker to signal the presence of an invisible dividing line. Underneath her encampment runs another type of line, this one very tangible: oil pipelines, whose flow from the oil fields of Alberta to Superior, Wisconsin —from which it then continues its journey towards refineries in the States and Canada— goes unimpeded.

One in particular, Enbridge’s Line 3 drew McManus here, 170km South from her home of Long Plain First Nation. A Dakota woman, whose ancestral lands stretch on both side of the arbitrary and alienating 49th parallel, she had come back from Standing Rock, where she helped organized the Sacred Stone camp, compelled to continue resisting the encroachment of oil infrastructure. “It’s not what I planned out for my retirement, to just sit on a road,” she told me when I met her, laughing.

The issue of Enbridge’s Line 3 hasn’t garnered an iota as much attention from the media or activists —even though it has been routinely opposed by environmental groups and Indigenous communities, mostly in Minnesota— as the Dakota Access Pipeline project; in large part because it’s already in the ground. It has been for over half a century. Its age means it’s not performing as the multinational corporation wishes. Out of the 760,000 barrels per day it once carried, less than half are now being pushed through. Hence the replacement project underway.

Here, replacement means leaving the existing pipe in the ground—what the industry calls “deactivation,” though it might be more aptly referred to as “abandonment”—and building a new one more or less alongside it. Capacity would return to the original level and Enbridge would have the option to also use it for heavy crude, which is considerably more damaging to the environment that an already considerably damaging energy source. In other words, this is not a replacement, as framed by Enbridge, but the building of a new pipeline, one that ought to elicit has much concern as the construction of TransMountain, Keystone XL, Dakota Access, to name but a few more infamous ones.

In the summer of 2019, I drove along Line 3, and a few other oil routes that connect the Oil Sands in Alberta to the refineries in Sarnia, Ontario—a road trip of more than 3,500 km in one direction—with the intention to examine how oil infrastructure affects and connects Indigenous communities across Canada. I visited McManus on a blistering hot summer day, meeting her when the sun was at high noon and setting up my own camper van’s awning to provide some shade as we talked. Her friend Alma Kakikepinace, a clan mother from Sagkeeng First Nation and a descendant of Sitting Bull, had also come to provide her with company for some days.

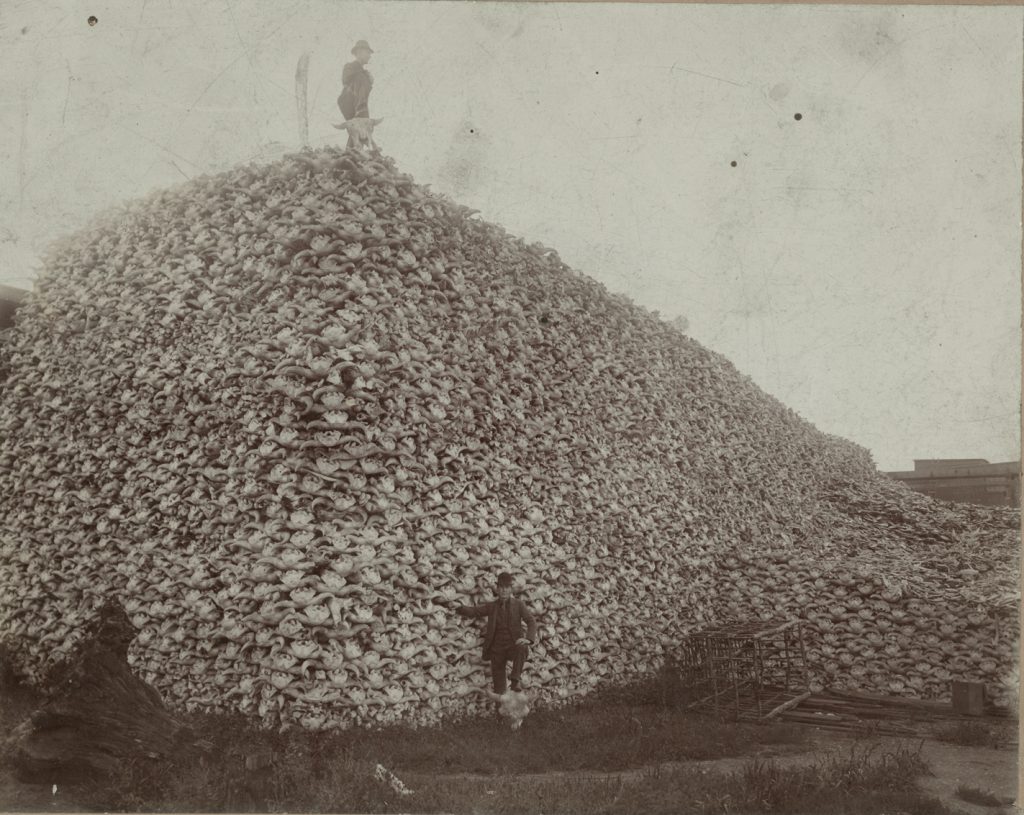

A conversation with McManus, who’s is as warm-hearted as she is defiant, meanders, drawing connections between issues such as the missing and murdered indigenous women, man camps, fracking, the disappearance of the buffalos from the Prairies, the sacredness of water, and many others. She’s well aware of how quixotic her resistance might appear to others, but that seldom phases her. “Am I accomplishing anything here?” she asked me pointedly. “Who knows,” she continued before I had time to articulate an answer. “By doing this, I’m showing that we’re not complacent. And I pray. I pray that the pipeline does not break or leak. I pray that it will cause no harm. There is currently no oil flowing. It’s been delayed multiple time. Did I play a part? I can’t say. But I believe in prayer.”

Officially, the reason for the repeated postponement is due to bureaucratic obstacles from the state of Minnesota, which has held back approving the necessary permits because of concerns over the environmental review. Initially slated to be operating by the end of 2019, the pipeline is now not expected to be turned on until at least the second half of 2020. But who’s to say that McManus’ actions haven’t accomplished anything? Witnessing her unwavering commitment and determination puts into question what we consider foolish, or rather who. Who is behaving foolishly in this situation? The woman who stands against a force that threatens the survival of a whole ecosystem? Or those who stand idly by, claiming there’s nothing that can be done?

McManus’ camp exemplifies exactly why fighting pipeline is of the utmost importance. Once they are placed in the ground, vanishing from sight, they become seen as ‘natural’, they are a fait accompli, something that can no longer be changed. Dayna Scott, an environmental lawyer, notes: “Energy infrastructure decisions, such as those to build pipelines, create complex systems of interconnection and exchange amongst natural, social, economic and built environments. At the same time, the pipeline is a fixed, durable physical structure that determines the routes of resource flows over time. It creates path dependence in a literal sense.”

In other words, once instituted, a pipeline route becomes entrenched. So much so, that we should refer to them as “corridors.” Next to the existing Line 3 there are six other pipelines. In total, within a width of a few dozen meters there are already five conduits for crude oil, one for refined oil, and one for natural liquid, all operated by Enbridge. Most are over fifty years old, with one being 43, one 9 and one 7. The new Line 3 would bring the total to eight conduits, all putting at risk the same aquifers and ecosystem. A few days after visiting McManus, I spoke to Scott. She reminded me that the more is invested in the oil infrastructure, the more we “lock ourselves in” that industry, and that this was largely due to its invisibility.

The added danger with perceiving ourselves as locked in an industry is that it limits our imagination, especially in regards to what our future can look like and the forces that can shape it.

By the time evening came, on the day McManus and I spent together, the sky over Spirit of the Buffalo camp had darkened. We sat watching the clouds, wondering when the rain would come. Kakikepinace especially. At once, she got up, got her bundle and began performing a pipe ceremony. Months ago, she had a vision of doing so.

As she went on, the sun burst through the clouds to the West, its rays so intense that they shot overhead, traversing the sky, still visible when they met the earth to the East. It seemed as if the earth itself was radiating, as if there were two suns. A rainbow appeared. Then a second. Two perfect arches straddling the border, getting more vivid as the two women sang in unison. When they stopped, the rainbows disappeared, the sun faded away and the skies darkened, once again.

Though this incredible empyrean display could be chalked to coincidence, it opened my eyes to the possibility of an embodied, ecological spirituality having a place in molding our future, if only to make us stop, appreciate and respect the ties that bind us to the more-than-human lives and environment around us, as well as to our histories and legacies. It also highlighted the strength and disruptive power of a single or a couple of individuals, reminding me that what is foolish is believing that we have no say in reimagining the boundaries of the future.