By: Michelle Yao

When I was younger, I used to fantasize about owning a house in the middle of Disneyworld. In this imagined future, I would naturally start each day with Mickey-shaped waffles and then end each night beneath bursts of Magic Kingdom fireworks.

While waiting for this dream to be realized, I resigned myself to pretending that the smokestacks surrounding my hometown made up our very own Cinderella’s Castle. In actuality, they are a symptom of our local economy’s reliance on the petrochemical and plastic industries. The swath of sixty-three-and-counting industrial facilities pressed up against our homes is known as “Canada’s Chemical Valley.” 1

At night, the gas flares hovering above the plants glow like fallen stars. The refineries are always running, but they’re at their most disarming in the dark. No longer a mere backdrop to rush hour traffic, their presence becomes undeniable to the city dwellers driving past. Most Sarnians have acclimated to—if not outright embraced—the oil and gas corporations’ toxic reign. Still, it’s sobering to contend with the visible manifestation of the slow violence that we tolerate in exchange for our livelihoods. Of course, denial is a luxury not everyone can afford.

Yesterday

The Valley feels like a permanent fixture, but it only became so well-fortified during World War II, when Sarnia was charged with producing rubber for the Allied forces. Long before all of this, Aamjiwnaang territory spanned both sides of the waterway that the refineries now pollute.

Then English and American settlers encroached on these lands, which were ceded in a series of treaties that created six separate reserves spread across both “Canada” and “America.” Colonial intrusion didn’t stop there. The 20th Century saw the state repeatedly annexing reserve land and selling it to oil and gas companies, all in the name of economic expansion.2

Today

Over 850 Anishinaabe people inhabit the 13 square kilometres that now constitute Aamjiwnaang First Nation. The Reserve is surrounded on all sides by Dow, Suncor, and Shell facilities. Everyone living in the surrounding area experiences health disparities as a result of our proximity to these plants. But in a prime example of environmental racism, Aamjiwnaang inhabitants remain by far the most exposed to Chemical Valley’s toxins. About 60% of the air emissions happen within five kilometres of their community.

Chemical Valley didn’t always exist, but it’s such a foreboding force, it’s hard to fathom that there was ever an era before its existence. But maybe we don’t even need to resort to this effort of imagination. The Valley’s greenhouse gas emissions are stoking up climate catastrophes. Fossil fuels are a finite resource. If state and industry leaders won’t stop the plants from polluting, then maybe the structures will soon destroy so much that there won’t be anyone left to man the castles’ stations.

According to the World Doomsday Clock, thanks to many global leaders’ failures to address climate change, we’re now 100 seconds away from the “midnight” that signals a man-made apocalypse. Cinderella’s rags reappeared when the clock struck twelve. When unsustainable industries wreck the world, will the remaining ruins eventually give way to renewed biodiversity—the reappearance of plants, animals, and everything and anything but those pesky, pernicious humans?

I hope that we’ll never unearth the answer to this question. As April Anson has pointed out, the impulse to embrace an indiscriminate end to humanity—as if it’s an inevitable conclusion—reeks of ecofascism. It implies that all humans are equally responsible for environmental crises. Never mind that Indigenous communities—like Aamjiwnaang—are persistently working against the ecological issues wrought by late-stage capitalism and colonial violence. At the same time, such communities are also the ones most impacted by the manmade harms that have been outsourced to their homes.

Tomorrow

When considering the future, let’s operate from a desire-based framework, as suggested by Unangax̂ scholar Eve Tuck. What kind of future do we desire for ourselves, for future generations? I’d like to see an end to Chemical Valley’s pollution. However, I don’t want this to come to pass as a consequence of large-scale destruction.

Many activists are already in hot pursuit of a viable future without industrial pollutants. Aamjiwnaang youth have specifically formed groups like the Green Teens to defend their land and culture. They’ve brought attention to their cause through rap performances, photography, and even an original documentary. If we want to shake the Valley off, then supporting such groups will be fundamental to seeing this paradigm shift through.

The photography of the Aamjiwnaang’s Green Teens being displayed at the Community Forum on Pollution and Action. This event took place on February 8, 2011, within the city of “Sarnia’s” limits. This showcase is specifically called ‘Photo-Voice,’ and it allowed the teens to “voice their views about living in an unhealthy environment in a healthy fashion.” Photograph of Green Teens display by Marcus Johnstone, via Flickr. Additional information about the showcase via The Starfish.

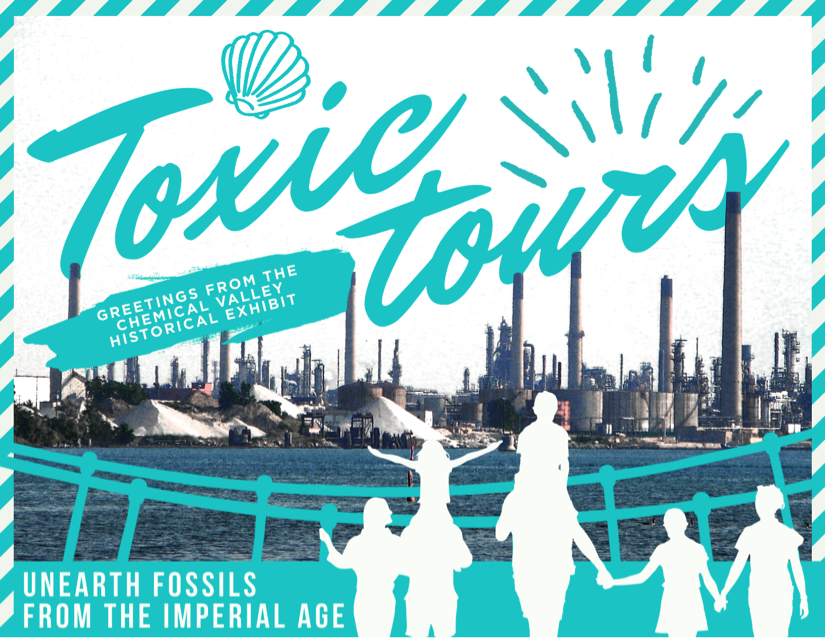

Vanessa Gray was the founder of the Green Teens. She is still a dedicated activist who, among countless other contributions, now helps organize “Toxic Tours” around the Valley. Every fall, visitors from all over bear witness to the Valley’s environmental destruction. The sights, sounds, and smells are a shock to those who haven’t been deemed expendable by the settler state.1

It’s not all doom and gloom, though. The tours also serve as an opportunity to share stories, honour Anishinaabe resilience, and build alliances so that everyone can work towards different, more desirable futures. After all, actual action must follow inspiration.

The Day After Tomorrow

Thomas King has noted how mass media and museum displays often implicitly insist that the “past was all [Indigenous people] had. No present. No future.”3 All the while, he observes, “Native writers [have begun] to use the Native present as a way to resurrect a Native past and to imagine a Native future.”3

This kind of resistance extends beyond writers, of course. The stories that the Green Teens tell with their creative displays are also powerful assertions of their community and culture’s past, present, and future. Not only are such local activists imagining decolonized futures, they’re also tangibly building paths to reach towards these outcomes.

Meanwhile, the Toxic Tours weaponize national historic sites’ rubberneck tour format to highlight Aamjiwnaang’s ongoing resistance. If museums are so compelling, then here’s one detailing the antiquated violences that the government has gone to great pains to preserve. If theme parks are so appealing, then here’s one that doesn’t need to pump artificial smells into the air to transport outsiders to a reality that might have previously been shuttered to them.

The stories that the Green Teens tell with their creative displays are also powerful assertions of their community and culture’s past, present, and future.

As one of few racialized immigrants living in Sarnia, I’ve often felt like a tourist passing through. I’m a settler that has reproduced processes of colonialism by trying to assimilate into a culture predicated on violence. Then again, I’m also an individual who’s lost a parent, a kindergarten teacher, and who knows what else to the chemical castles that I’ve spent the second half of my life escaping.

That’s the tricky thing with toxins. As Alexis Shotwell has observed, “[r]ich people have an easier time enacting the kind of redistribution or avoidance of poison … [but] these practices are temporary and illusory; we cannot in the end be separate from the world.”4 Anyone who thinks that they’re untouchable should take a second look at the refineries ruining the atmosphere we share.

In any case, now that midnight’s about to strike, I’ve found myself turning back to my hometown and envisioning a better future set in the same space. Disney’s corporate spell has worn off. I now dream about worlds without castles of any kind. Instead of superimposing Fantasyland’s image onto the refineries, I’d now like to see a world where clean air and clean drinking water for all isn’t solely confined to my wildest wishes.

In my imagined future, Green Teens and other desire-driven change makers will be the ones leading the charge on casting aside capitalist contaminants. We’ll act in time and reverse the most devastating impacts of climate change without losing anything valuable on the way.

Maybe the future will still have Toxic Tours, but the tours will be describing archaic practices that have long been abandoned. Let these unsettling records show us why these self-destructive smokestacks should remain locked in the past. Future generations will learn of these losses, but I hope that they won’t mourn them. I know I won’t.

Print Works Cited

- Gray, Beze, and Alice Damiano. “Aamjiwnaang Toxic Tours.” Local Activism for Global Climate Justice: The Great Lakes Watershed, edited by Patricia E. Perkins, Routledge, 2019, pp. 183-191.

- Wiebe, Sarah Marie. Everyday Exposure: Indigenous Mobilization and Environmental Justice in Canada’s Chemical Valley. Kindle Ed., UBC Press, 2016, ch. 5.

- King, Thomas. The Truth about Stories: A Native Narrative. Kindle Ed., House of Anansi Press Inc., 2005, ch. 4.

- Shotwell, Alexis. Against Purity: Living Ethically in Compromised Times. Univ of Minnesota Press, 2016, p. 85.