In 2020, California gained international attention after it experienced some of the worst wildfires in the state’s history. Climate scientist Daniel Swain described the fires as having “no statistic or dimension […] that wasn’t astonishing or horrifying”. These fires spread rapidly across the West Coast and smoke travelled as far as the East Coast. Though less discussed, Ontario also faces a future of severe wildfires, especially in the province’s boreal forest region. As a result of climate change, wildfires are harder to control and more frequent, leading to many intersecting losses.

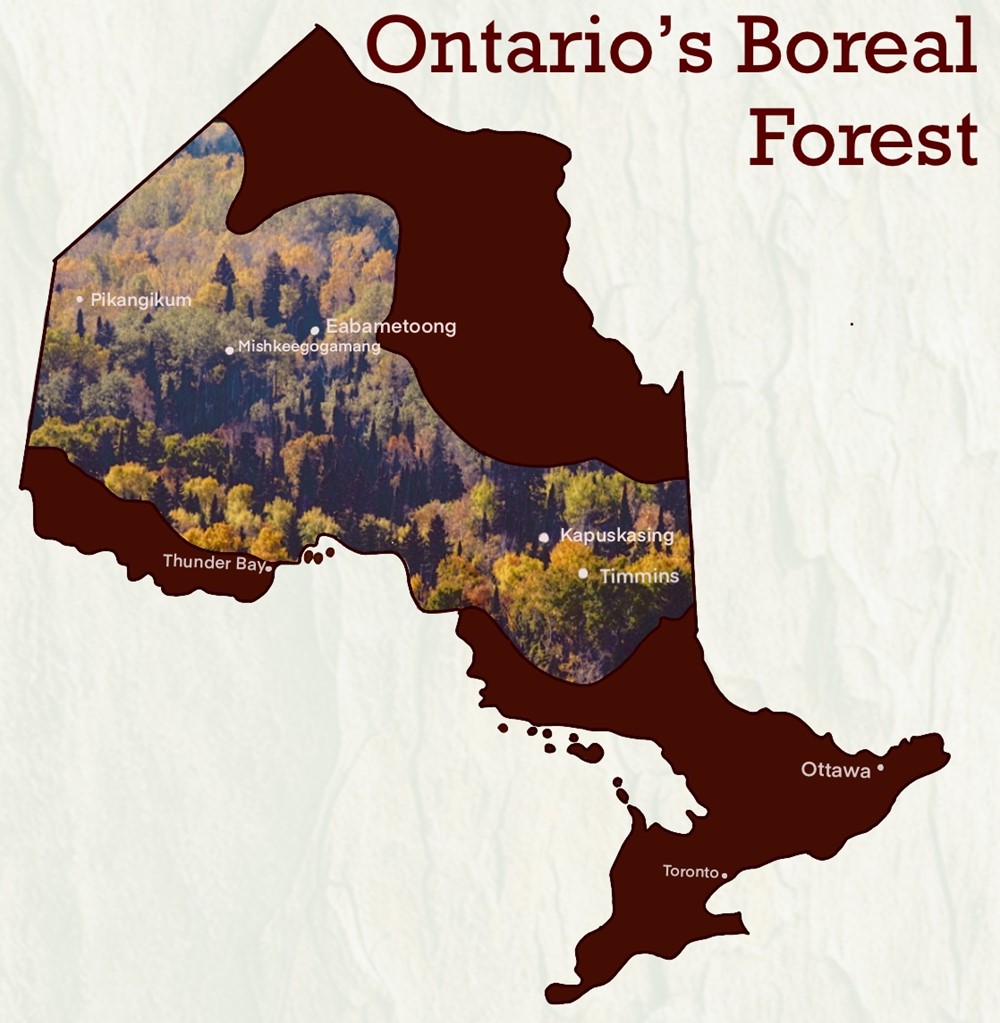

Ontario’s boreal forest region is located in the northern half of the province, occupying 50 million hectares of land and accounting for two-thirds of all Ontario’s forests. The boreal forest is a complex environment that requires wildfires to regenerate itself and sustain its inhabitants, whether they be plant or animal. The forest is home to many fire-dependent species such as spruces, jack pines, and balsams, which use a wildfire’s extreme heat to open their seed cones and reproduce. These wildfires also fertilize the soil, benefiting non-fire-dependent plants by giving them a chance to regenerate.

Conflicting Perspectives on Wildfires

Ontario’s boreal forest overlaps with the traditional territories of the Anishinaabe and Cree, and their relationship with the land influences their cultural practices. For the Anishinaabe, fire is a complex being and an important aspect of living in the region. As Whitehead Moose, an elder at Pikangikum First Nation, notes: “The Creator has a match and that match is the thunderbird. He brings that match to the land when the forest gets too old and can’t grow anymore […] After the forest is burnt new growth starts” [1]. In addition to lightning fires, the Anishinaabe use controlled burns to maintain their communities and broader territory. These prescribed burns encourage game animals to reproduce, refresh berry patches and maintain portage routes and campsites [2]. No matter the source, fires in the boreal forest are part of the sustainable worldview of the Anishinaabe. Understanding the function of fire in the boreal forest reveals how forests are a place for cross-species relationships.

In contrast, governments, forestry companies and other colonial structures view wildfires as a risk to their bottom line. Invest in Ontario, a provincially sponsored website, notes that Ontario’s forestry industry is worth $18 billion annually and its forests are home to many high-valued woods. Whilst prescribed burns are sometimes used, there are great financial incentives for the government to prevent timber loss. Although wildfires have an ecological value, they have no monetary value and so governments favour prevention through suppression over other practices. Settler society’s view of resource extraction and the use of fire suppression tactics to protect profits disrupts the natural and necessary cycles of the forest.

Threats to the Boreal Forest

While there are a number of factors increasing the vulnerability of the boreal forest over the next century, all are ultimately connected to climate change. One study suggested there were two possibilities of what the boreal forest of the future might look like. In one vision, warmer temperatures could lead to a drier climate. Such a climate would provide more opportunities for fires to spread due to increased availability of fuel and a reduction in the precipitation that would naturally extinguish wildfires [3]. Alternatively, a moister environment would result in more storms and lightning activity, thus increasing wildfire ignitions by 75-140% by 2100 [4]. Additionally, increasing can temperatures expand the range of non-native insect species which damage and kill trees [5]. An unhealthy forest is at more risk of catastrophic wildfires than a healthy one.

Fire Management, Evacuations, and Compounding Catastrophes

Though the increasing severity and frequency of fires will peak within the next century, Northern Ontario’s 2020 fire season was below average. This was a result of several factors such as more rapid responses from fire crews and a more balanced weather pattern. Despite this, the impact of these fires was noteworthy in the evacuations of Red Lake and Eabametoong First Nation, a process that was complicated further by the remoteness of most communities in the boreal forest. From Eabametoong, officials evacuated 550 of the nation’s most vulnerable residents via aircraft to Thunder Bay, Timmins, and Kapuskasing. The simultaneous fire near Red Lake resulted in the entire town of over 4,000 requiring shelter.

Before evacuations, Eabametoong Chief Harvey Yesno expressed anxiety over delays that prevented him from beginning the process. These delays resulted from resources being tied up by the fires affecting Red Lake and demonstrate the obstacles associated with increasing fires. In a future with more wildfires, managing multiple fires and evacuations simultaneously difficult, and any delays only increase people’s exposure to smoke and danger. The evacuation was also complicated by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the risks that evacuees faced in leaving their community. Evacuees from Eabametoong were those most threatened by COVID-19, such as children, elders, and those with medical conditions. The experience of evacuees demonstrates that climate change is not a singular catastrophe. The effects of future wildfires will compound with many other crises brought by climate change, making fires more difficult to manage and lead to more devastating effects.

Wildfires, Landscapes, and Indigenous Futures

The future of wildfires in the region will alter the character of the ecosystem entirely. Under current trends, the future of the boreal forest is difficult to predict. Perhaps some of the forest may survive due to the number of fire-dependent species in the region, but it still would not be the same. With fires lasting longer and becoming more frequent, it would no longer be safe for people to inhabit it. Smoke would paint the skies and coat the lungs of not only those in the immediate region of the fire but potentially further. Exposure to smoke would lead to many health complications, especially for those with pre-existing conditions like asthma. Perhaps the heat of the new climate will make the region devoid of trees. The destruction of the boreal forest is a complex and multilayered event, affecting not only plant and animal habitats but the cross-species relationships and the land-based cultural practices of Indigenous people.

As it is their traditional territory, there are many Anishinaabe communities within the boreal forest. However, this means that they are also most affected by the increase in wildfire activity. The losses they face not only encompass material possessions but more significantly, affect their land-based cultural practices. As Leanne Betasamoke Simpson notes: “Indigenous education is not Indigenous or education from within our intellectual practices unless it comes through the land” [6]. Evacuations place people hundreds of kilometres away from their homes. A future where wildfires and evacuations are more frequent will complicate the relationship many Anishinaabeg have with the land. Though traditions are unlikely to be forgotten, the transformation of the land due to climate change will alter how these traditions are practiced and shared.

The increase of wildfires also risks reproducing traumatic histories for Indigenous communities. When interviewing residents of Mishkeegogamang Ojibway Nation who hesitated or refused to leave during evacuations, researchers noted that much of it stemmed from the colonial legacy of Canada. The evacuations reminded some residents of the government’s history of controlling Indigenous people’s movement by removing them from their land, forcibly moving them onto reservations and placing their children into abusive Residential Schools [7].

In climate justice, it is important to consider how disasters affect communities differently. To maintain the approach that ignores the needs of Indigenous communities is to lose sustainable practices, reproduce traumas, and continue to perpetuate harmful colonial structures.

Endnotes

[1] Miller, Andrew Martin, and Iain Davidson-Hunt. “Fire, Agency and Scale in the Creation of Aboriginal Cultural Landscapes.” Human Ecology, vol. 38, no. 3, 2010, pp. 401–414., doi:10.1007/s10745-010-9325-3, 407.

[2] Miller and Davidson-Hunt, “Fire, Agency and Scale in the Creation of Aboriginal Cultural Landscapes,” 403.

[3] Wang, Xianli, et al. “Projected Changes in Daily Fire Spread across Canada over the next Century.” Environmental Research Letters, vol. 12, no. 2, 2017, p. 025005., doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aa5835, 8.

[4] Wang et al., “Projected Changes in Daily Fire Spread across Canada over the next Century,” 2.

[5] Ramsfield, T.D., et al. “Forest Health in a Changing World: Effects of Globalization and Climate Change on Forest Insect and Pathogen Impacts.” Forestry, vol. 89, no. 3, 2016, pp. 245–252., doi:10.1093/forestry/cpw018, 246.

[6] Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake.As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance. University of Minnesota Press, 2017, 154.

[7] McGee, Tara K., et al. “Residents’ Wildfire Evacuation Actions in Mishkeegogamang Ojibway Nation, Ontario, Canada.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 33, 2019, pp. 266–274., doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.10.012, 272.

Works Cited

CBC News. “Eabametoong Chief Anxious to Start Evacuations Due to Forest Fires.” CBC News, CBC/Radio Canada, 12 Aug. 2020, www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/eabametoong-forest-fires-1.5682770.

—–. “Members of Eabametoong First Nation Arrive in Thunder Bay Ont., Following Evacuation.” CBC News, CBC/Radio Canada, 12 Aug. 2020, www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/eabametoong-first-nation-evacuation-fire-1.5683344.

—–. “More Crews Sent to Fight Forest Fire near Eabametoong First Nation in Northern Ontario.” CBC News, CBC/Radio Canada, 20 Aug. 2020, www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/crews-forest-fire-eabametoong-1.5693738.

Diaczuk, Doug. “Northwest Had below Average Forest Fire Season.” TBNewsWatch.com, Dougall Media, 31 Oct. 2020, www.tbnewswatch.com/local-news/northwest-had-below-average-forest-fire-season-2838325.

The Guardian. “California’s Wildfire Hell: How 2020 Became the State’s Worst Ever Fire Season.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 30 Dec. 2020, www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/dec/30/california-wildfires-north-complex-record.

“Forestry.” Invest Ontario, Government of Ontario, 30 July 2020, www.investinontario.com/forestry#diverse.

McGee, Tara K., et al. “Residents’ Wildfire Evacuation Actions in Mishkeegogamang Ojibway Nation, Ontario, Canada.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 33, 2019, pp. 266–274., doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.10.012.

Miller, Andrew Martin, and Iain Davidson-Hunt. “Fire, Agency and Scale in the Creation of Aboriginal Cultural Landscapes.” Human Ecology, vol. 38, no. 3, 2010, pp. 401–414., doi:10.1007/s10745-010-9325-3.

Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. Forest Regions. Government of Ontario, 17 July 2014, www.ontario.ca/page/forest-regions.

—–. Prescribed Burns. Government of Ontario, 17 July 2014, www.ontario.ca/page/forest-regions.

Money, Luke, and Richard Read. “Smoke from California Wildfires Reaches the East Coast and Europe.” Los Angeles Times, 15 Sept. 2020, www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-09-15/smoke-california-wildfires-reaches-east-coast-europe.

Ramsfield, T.D., et al. “Forest Health in a Changing World: Effects of Globalization and Climate Change on Forest Insect and Pathogen Impacts.” Forestry, vol. 89, no. 3, 2016, pp. 245–252., doi:10.1093/forestry/cpw018.

Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Wang, Xianli, et al. “Projected Changes in Daily Fire Spread across Canada over the next Century.” Environmental Research Letters, vol. 12, no. 2, 2017, p. 025005., doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aa5835.