By: Maddie Robson

The current practices of producing food for human consumption in North America have shifted the relationship between social and environmental systems, causing a wide range of loss and suffering within the Anthropocene. Right now, global food systems are not sustainable; how we eat and how we produce food is leading to irreversible catastrophic transformations in the global environment.

Food economies under capitalism are deeply rooted in colonial mechanisms and values. The current orientation of corn in industrial agriculture has enforced a capitalist structure of food production in North America, causing a displacement of sustainable systems through the destruction of the environment. From a socioecological perspective, the intersection between Indigenous corn practices and colonial methods in the Global North has illuminated the loss of connection between people and their food. The system currently orders a range of social relations by controlling, commodifying, and distributing products that illicit Western modernity, constructing the inevitable decline for Earth systems.

Colonial systems and values have derailed the ties between human connectivity and the production of corn. With efforts to continuously combat the century–long culture of colonization, Indigenous groups of North America share commonalities regarding food sovereignty: the belief of the physical territorially and kincentric universe. Food sovereignty approaches the natural environment as intertwined with its species, understanding that every being is a mere part of the universe as its whole. The reciprocal connection of an affinity between people and place “create[s] a rural economy which is based on respect for ourselves and the earth’’. The approach to achieving food sovereignty in agricultural production stems from Indigenous practices, focusing on ecological and sustainable methods for the people and the environment.

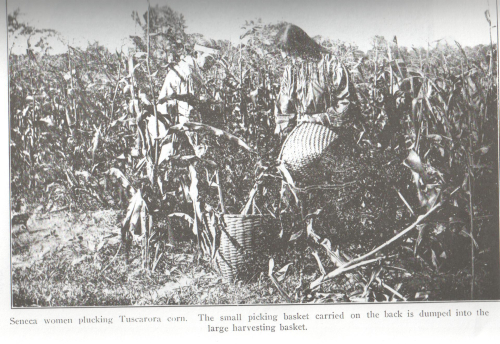

Indigenous communities have followed a traditional paradigm when farming corn: enough is grown to provide a three-year supply, avoid mechanical tillage, and the entire crop is used fully throughout the harvest and storage practices. Thus, understanding the wisdom and practical knowledge during the harvest, preparation, consumption, and long–term management of food resources contributes to a personal “more than ourselves” ideology.

A brief lesson investigating the rise of corn in history and its effects on global agriculture. Video by TED-Ed via Youtube.com

Colonial food and agriculture infrastructures desire to disrupt and interfere with Indigenous production systems led to state technologies working towards destroying and replacing their practices with a civilizing force of modernity and governance. After the initial waves of extermination and erosion of Indigenous people and their food operations in the 1800s, colonial techniques continued to ignore Indigenous subsistence activity and erased years of prior cultivation of crops. Initially, Indigenous communities utilized the corn plant through the milpa agricultural practice, as corn is a staple in their diet and cultural practices. But with the threat of settler colonialism ideologies, governments neglected the responsibility to protect this natural resource and promoted unsustainable megaprojects and policies.

When growing corn, Euro-centric practices altered the production techniques by changing the original land systems. Implementing fertilizers, monocropping, and tilling methods account for wasteful land and water use and increased air pollution levels, ultimately dismantling the earth’s natural habitat. The diverse ecosystems, including wildlife and plants, can barely survive within these colonial practices. This establishment forces Western principles to regulate corn and devalue the conservation and relationship between product and environment.

With the political change of food movements, settler colonialism provided a baseline that enables and accelerates change in food production and distribution in the Global North. In its origins, settlers had to specialize in cash crops to obtain credit. Corn is a cheap seed that can grow in more places and produce more products than any other grain. So, the industrialization of agriculture quickly became commoditized and globalized to trade in international markets. By progressively improving machinery and increasing the production rate for consumption, the agribusiness became more concerned with seeking profits than feeding people fresh and healthy food. North America’s rich prairie soils and cheap fossil fuels allowed the revolution to exploit resources and corn crops to industrialize our food supply. The former socialized economic, political, and cultural factors regarding the health and wellbeing of people and the environment were no longer practices. Now permeating everything we eat, simply put, capitalism has turned an essential item into a commodity.

Currently, North American food companies intention is not to promote life, health, or happiness. The purpose is to make money for executives and shareholders. Food that is not a commodity has no value for a capitalist. By investing in research and development strategies to maximize corn profits, the agricultural industry has pushed production beyond the local market. And sure enough, corn has crept into every part of the food system. Our entire diet has been colonized by this one plant. Corn is ubiquitous, and due to subsidies fostering overproduction, the marketplace finds new ways to incorporate and favour it. Large corporations like ADM, Cargill, Monsanto and DuPont use the globalization practices of corn and sequentially portray the ignorance towards global warming and destruction of the ecosystem. This money-making doctrine governs a power relationship that self generates, purely out of greed and lack of empathy, only to perpetuate profits for the corporation at the expense of consumers and biodiversity.

On top of that, marketers of food products are savvy—they know what to say to elicit a response from consumers. Since the rise of agricultural industrialization and processed food, capitalist food systems focus on profits over human value. Marketers find innovative ways to sell their overabundance of inexpensive, non-nutrient-dense, industrial foods. So, in a fiercely competitive food market, advertisements use phrases like ‘Increase Performance’ ‘Treat Yourself’ and ‘No Sugar Added’ to form an aesthetic that manipulates an individual to buy a product. Promoting both critical and luxury items, consumers buy into the charade and ultimately reinforce their disconnect with the origins of where their food comes from. Being unaware has allowed the industrial production of corn to be used and abused as an indistinguishable product with coercive measures to sell more. This capitalist mechanism has become an instrument for profit in the Global North.

Coming to terms with how corn has transformed the way the world eats, it is vital to pinpoint how society is ingrained to think about the food system in a certain way, or rather, not think about the food system at all. Since consumers lack awareness and control over the production of corn, it is valuable to learn the flaws of modern industrial farming practices and how corn may be leading society towards ecological disaster. The current agricultural methods are influencing pollution rates, biodiversity loss, social control, and the unsustainable changes in water and land use. These contribute to the deterioration of the Anthropocene. So we must look back. By learning how Indigenous communities harvest corn, it begins to integrate ideas and autonomy within the development of alternative modes of production, combating the current capitalist food system.

Knowing that a commodity is a matter of social relationships, thinking of corn as something other than revenue can allow our goals as an economy to shift. A transformative understanding initiates an intellectual concern for freedom and agency within the consumer and product, undoing the dominant discourse. This conversion of the Global North’s unsustainable corn practices can be the key to social and environmental connectivity, consciousness, and concern, ultimately changing the way we regard food.