When Hurricane Sandy struck New York in 2012, it pushed a deluge of water through the city, breaking the city’s coastal defences with ease, the storm estimated to have caused $19B of damage and tragically claimed the lives of 43 people. It’s impossible to predict when another storm like this will hit New York, but the likelihood of flooding is rising. In the face of rising sea levels, New York concurrently deals with the insidious nature of gentrification, with communities most affected by both rising sea levels and rising rent being Black communities. While gentrification began in the 1980s and 90s in NYC, the effects of climate change are far more threatening and far more evident now. In Climate Change Adaptation in New York City, Cynthia Rosenzweig and William Solecki write that “environmental conditions as we experience them today will shift, exposing the city and its residents to new hazards and heightened risks. We will be challenged by increasing temperatures, changes in precipitation patterns, rising sea levels, and more intense and frequent extreme events.” By understanding both the racial makeup and cultural significance of communities in New York City, and subsequently categorizing them to see how climate change affects these respective neighbourhoods, we are able to better understand what effect socioeconomic demographics have when it comes to thinking about who stays safe in the face of a changing Earth.

Gentrification is a term that often invokes an image of luxury condos rising from the rubble of public housing developments and independent community run businesses. Climate gentrification, however, throws in the additional factor of a changing global climate that ultimately results in the displacement of low-income people of colour who can no longer afford to live in their homes. Climate gentrification creates a sort of cyclical violence: the prospect of purchasing a home that will be underwater or in the middle of a desert in fifty years is unappealing to homebuyers and makes weather-resilient neighbourhoods more desirable. As a result, homes that are protected from floods by being further north or more inland increase in price, making them unaffordable and unattainable for low-income homebuyers, putting these low-income, and often racialized folks, at risk. Aparna Nathan of Harvard University writes that this cycle “leaves already-vulnerable populations at the mercy of life-threatening weather events”. Ultimately, the cycle of violence is continued and encouraged in the face of both climate change and gentrification, and through the exploration of the connection of the two, we can see exactly what the impact of shoddy politicians and poor infrastructure can do and does to racialized communities.

Figure 1 are two side by side maps highlighting the change expected in New York City in coming years. NYC is a coastal city, meaning the proximity to rising water levels is a direct threat to both the infrastructure of the city, but more importantly, its residents. The maps shown above are a rendered image created during Climate Central’s project, Surging Seas: Extreme Scenario 2100, a Google Map extension made to show how major cities would look in coming years, in the face of rising sea levels and melting glaciers. The above maps demonstrate how rising sea levels would mean most of New York City’s major financial area would be flooded with water from the Hudson River seeping into densely populated Brooklyn and the West Village.

Brooklyn, though rather gentrified with young white professionals, is neighboured by boroughs like Queens, and the Bronx; places where there are multi-generational homes of low-income Black and brown families. According to the US Census, the Bronx consists of 43.6% Black families, and 56.4% Latinx, with the median household income being about $40,000 USD per year. While living costs in New York rise and the threat of climate change becomes a reality, those living in neighbourhoods most affected by flooding are able to flee because of their already rapid gentrification, while leaving the low-income racialized people of neighbouring boroughs to fend for themselves. This map of rising sea levels not only creates a tangible visual for New Yorkers to imagine their futures, but puts the stark, unmistakable reality of climate change and its impacts to the forefront. Rohit Jigyasu explains that “while there is a definite need to continue undertaking further research through a collection of highly calibrated data and sophisticated modelling for developing probable climate change induced scenarios for the future, it is equally important to invest in translating our progressively enhanced understanding of climate change risks into simple, achievable practices for day to-day management of cultural heritage”. Many communities at risk of gentrification are ones that, again, consist of racialized multigenerational families that have lived and thrived in the hustle and bustle of New York City for years. The loss of their home structures or familial homes is indicative of a larger loss of cultural heritage and knowledge of the area and its people passed down through storytelling and community practices.

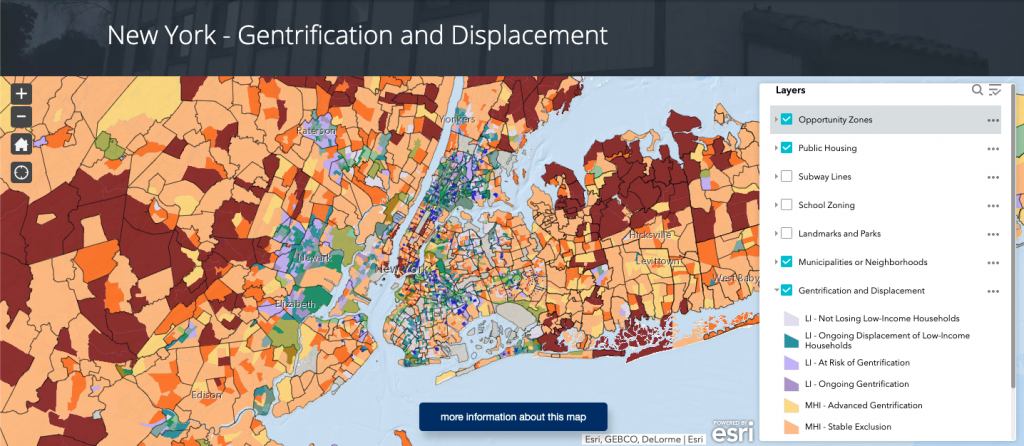

The above map, created by the Urban Displacement Project, maps the New York metropolitan region, while highlighting which neighbourhoods are facing varying forms of displacement. With the layer tool on the right, one can adjust to see everything in each borough of New York City, and New York State, highlighting school zones, municipalities and neighbourhoods, “opportunity zones” where land may be scouted for new development, and ongoing displacement, which marks neighbourhoods that are at risk of gentrification, or are experiencing ongoing gentrification. The Urban Displacement Project writes that “understanding displacement in New York is critical given its housing crisis: rising rent burdens, homelessness, loss of rent-regulated housing, public housing deterioration, and more. With new interest in the New York region from big tech firms like Amazon, Apple, and Google, as well as new federal policies like Opportunity Zones and local actions that seek to harness market-rate development to boost the supply of affordable housing, it is time for New York to look more carefully at displacement”. As previously mentioned, the this cycle of violence propagated by displacement is one further stoked by the impending reality of rising sea levels, changing climates, and a warming Earth.

Together, both Figure 1 and 2 reveal that communities outside of the metropolitan core are often not seen as facing displacement risks, yet the maps show that some of these towns are undergoing their own displacement processes in what might be seen as a sort of ripple effect that has larger impacts, especially with these metropolitan core communities being the first to be affected by rising water levels. Ultimately, this mapping helps us to understand current gentrification, in the face of impending climate disaster, and adequately understand which communities need the most tangible support rather than new developments.

Journalist Amali Tower aptly notes that while “climate change is a contributing factor to [residents] eventual displacement…it’s important to untangle and decipher the economic reasons alongside the climate reasons so we can effectively advocate for meaningful policy and legislation that protects vulnerable communities from the slow onset impacts of climate change and before, during and after climate fuelled disasters. If not, we not only risk displacement, but also risk losing the diversity – in all its forms – that makes up the entire fabric of what constitutes New York City”.

The protection of New York City is imperative, not only because of its tourist revenue or celebrity pull, but because it is home for so many low income, Black and brown people who know those boroughs like the backs of their hands. Climate change is our responsibility to map, to halt, to manage, for the sake of the preservation of the very thing that makes NYC such a hotspot for visitors and celebrities alike in the first place: its people.