Our in the workshops… blog posts are designed to provide readers with a behind-the-scenes glimpse into TSDC’s performance creation process. In this three-part series, Catherine (Graham) and I (Helene Vosters) discuss storycircles. To get us started, we begin with a brief description of what happens in a TSDC storycircle, followed by part one of our conversation focused on how the storycircle structure is ritualized to invite participants into a collective creative process.

What a TSDC storycircle looks like

The storycircle begins prior to the first workshop when we send participants this prompt:

Imagine what Hamilton might be like ten years from now if it were to become a much better city. What do you imagine life would be like in that much better Hamilton for people with experiences like yours? Please bring an object that will help you tell a 1-3 minute story about something a person with experiences like yours might do in a much better Hamilton 10 years from now. How would life be different for them?

At the first TSDC workshop gathering, after checking in and sharing food (something we do at all TSDC workshops), the group sits in a circle. At the centre is a small cloth-covered table for everyone to place their object on. The facilitator (usually Catherine or Melanie Skene) briefly explains the process and then models it by picking up her object and telling a story based on the prompt. Throughout the storycircle, only the person holding the object speaks. Everyone else is asked to listen, and after the speaker completes the story everyone else in the circle has the opportunity to respond.

After each story, each listener is invited to hold the storyteller’s object. The object is passed around the circle until everyone, including the storyteller, who goes last, has a chance to respond to the following questions.

What colour is this story?

What emotion do you associate with this story?

Complete the sentence: “This is the story of the person who…”

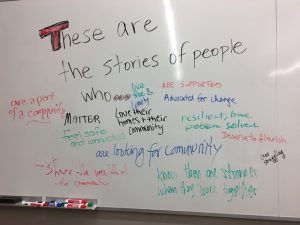

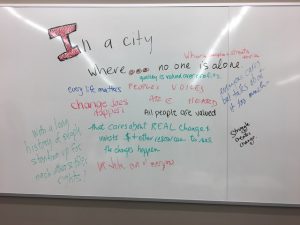

Once each person’s story has been shared and responded to, the group brainstorms responses to the fill-in-the-blank sentence, “These are stories of people who _________ in a city where ____________.” The sentence and responses are written on a whiteboard or a large sheet of paper and become the foundation for a post-storycircle discussion exploring the questions: “What do the statements on the whiteboard tell us about the kinds of stories we want to tell and the kind of city we want to live in?”

Storycircles: Time-outside-of-time

I like to have a low table with a cloth over it, which makes almost an altar for the storycircle objects… because I think an altar says, “These things are important.” And isn’t that what the sacred is? It’s that which deserves our attention.

— Catherine Graham, TSDC Principal Investigator

H: While storytelling circles are practiced in many communities, you’ve developed a way of working with them that includes a prompt, an object, and a feedback structure that make the circles feel kind of ritualized.

C: I deliberately developed storycircles in a ritualized way in the sense that performance studies understands ritual,[1] not necessarily in the sense that religious studies understands ritual…

H: …ritual as in creating a space outside of the day-to-day?

C: Creating a space outside of everyday time strikes me as important, which is kind of interesting in terms of theatre because I also think that that’s what stages or performance areas do. They create a space-time that is out of everyday space-time in which you can explore possibilities that might get ruled out in everyday existence. A basic rule of theatre is that what happens on stage won’t have immediate effects in the world of the audience. One of the most obvious examples of this is that, if we see someone pull a knife on stage, we react very differently than we would if we saw someone pull a knife in the lobby.

So in the ritual, participants are working in this time-outside-of-time, but the material object links it to their everyday life in some way. Particularly with the TSDC project, this strikes me as important. You don’t have to invent a new world out of whole cloth — there are things in your life, in your world, in the stories that you tell that could be the material for building this new world, for building this new vision.

H: Another element of how you facilitate storycircles is by using a prompt. Rather than an open invitation to share whatever comes to mind in the moment, or asking them about past experiences, the prompt asks participants to tell a future-focused “story.”

C: It’s a way of saying, “We are now entering creative space.” I think that’s something that’s quite particular about what we’ve done with TSDC. People often assume that because we are working with people who have lived experience of the situations we are staging, they will simply act out a replica of what they have experienced. With TSDC we very deliberately said, we’re not going to do that. We want to focus on what people want to happen, not on what has happened.

One of the reasons for our emphasis on future goals is that when we first heard from participants during the recruiting process, they kept saying over and over, “you need to realize how painful it is for us to tell stories of the bad things that have happened to us.” So that’s why the TSDC storycircle prompt is important to our project: we want to be clear that we are not just asking about their experience of a particular situation, or their proposed solutions to a particular problem, we are asking about the kind of world they imagine creating together.

I’ve been thinking a lot about that. I’ve been thinking about the relationship of desire and subjectivity. Can you be a social subject in the world without being encouraged or allowed to articulate desire? It does strike me that it’s hard to see yourself as a subject, as someone who can act on the world, if you are never invited to think about what you want the world to look like.

to be continued…

[1] See Schechner, Richard. Chapter 3 “Ritual” in Performance Studies: An Introduction (second edition) Routledge: New York, 2006.