High-rise Buildings as Relational Spaces

Work on our newest play, “When My Home is Your Business…” is moving forward fairly quickly now. One of the crucial steps in making theatre out of the stories participants shared (see our previous blog entries) was to figure out how characters might actually come in contact with each other in the shared space of urban apartment buildings.

When we asked participants to imagine Hamilton ten years from now as a much better city, it was striking how unique each of their stories was. It became clear that each of us was coming from a particular experience of moving through the city. Some knew the city from the point of view of newcomers to Canada and others as long-time residents. Some knew the city from the point of view of single professionals, while others saw it through the eyes of retirees with grandchildren.

Despite these differences, when we asked participants to create a non-verbal image of Hamilton as it actually is, they had no problem using their bodies to create a sense of a shared physical environment that was immediately understood by all. In part because we had recruited participants for their lived knowledge of challenges tenants face, many of these images centred on how people relate to each other as they move through Hamilton’s large rental apartment buildings.

In the weeks of theatrical exploration that followed, our participants created dynamic images of how everyday life unfolds inside Hamilton’s apartment buildings. These images prompted our research team to think about how inter-personal relationships evolve in such places, and how the social dynamics that take place in a high-rise may facilitate and/or prevent people from living together in harmony.

What became increasingly clear as we explored these initial images was how the story we needed to tell was grounded in a very strong sense of place: that of a multi-story structure comprised of both private dwellings and common spaces that people are expected to pass through rather than gather in. From the very beginning of the workshop process, participants emphasized how building management often goes to some trouble to ensure, for instance, that people don’t linger or organize to meet as groups in the lobbies of buildings.

Translating Relational Space to the Stage

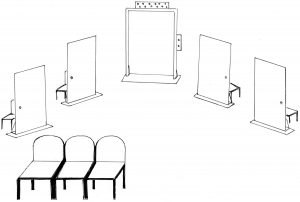

Because this is theatre, we needed a set. Contrary to what many people might initially assume, a theatre set is not so much about replicating the “look” of a particular space. What is more important is to create the space in which characters can move into an out of particular kinds of relationships. In our case, this meant a space where each character is expected to have control of the small space behind their own door, but where they must also move through common spaces where they encounter other tenants.

Our designer, Melanie Skene, whose gorgeous puppets some of you may have seen at Take Back the Night or at performances by the Hamilton Aerial Group, came up with a great way of showing this, as seen in the drawing at the top of this post. The set is simple, easily transported, and – one of the things that was most important to us – it asks the audience to imagine a space that may remind them of spaces they know, rather than suggesting that the action of the play could only take place in one particular building. Once we had a clear sense of the space, performers were able to weave together snippets of various stories by improvising encounters centred around the issues they have experienced, directly or indirectly. As they moved through the space telling these stories, the world of the play started to come to life in exciting ways.

On one level, creating the space of the action was important simply because this is theatre, not a series of speeches or a policy report. (French theatre theorist Anne Ubersfeld, in her book, L’Ecole du Spectateur, actually defines theatre as “talking bodies evolving in space.”) But through our workshops we quickly realized that defining the space in which we could imagine this world is about much more than the demands of a particular art form. As we started to tell stories by moving through this particular space, we quickly saw how the organization and control of any space opens the possibility for some types of relationships, and makes others much more difficult.

The question of the kinds of relationships that can happen in particular spaces, it seems to us, is not only a problem for theatre-making. Rather, thinking about space in our theatre-making process has pushed us to also think about the ways in which the control of space affects the kinds of relationships that will be possible in Hamilton ten years from now. This is already a pressing question where “my home is your business…”

Are there ways in which you have seen the organization and control of space affect the kinds of relationships people can develop in Hamilton? We’d love to have you share your observations by commenting on this post!