Our in conversation with … series of posts introduces readers to the people behind the Transforming Stories, Driving Change project. These are the artists, researchers, and community participants who desire Transforming Stories to make a substantive contribution to civic engagement in the city of Hamilton.

Jennie Vengris is a co-Investigator on Transforming Stories, Driving Change and Assistant Professor in the School of Social Work at McMaster University.

I think the method and process is a good one. It elicited all sorts of conversation. And it did get some of us who are firmly in our heads, out of our heads a little bit, which I think it is hopeful.

— Jennie Vengris

So what is your primary role on Transforming Stories?

I’m on the leadership team of Transforming Stories, and I joined the project in its early stages. I am relatively new to academia, but I have a 10-year history of doing community work in Hamilton. So, part of why Chris invited me was because I have a lot of contextual understanding of the community, a good sense of the politics and players and engagement processes, all of the stuff that you won’t read about on a website or know formally. So, I think that’s why [the project’s principle investigators, Chris Sinding and Catherine Graham,] brought me on.

So you were involved in the pilot. Were you able to take part in the performance-as-research activities?

So we had been talking theoretically about the method based on the research evidence that Catherine had reviewed. And it didn’t sort of land with us. We kept on wondering, what would this look like? And what would it feel like? So, Catherine invited the research team to participate in the process together, as a group. I was terrified because it was asking us to open up emotionally and vulnerably in front of people in a way that we hadn’t before. So, I felt nervous about that initial process. But it went well!

I think what made it go well was Catherine’s careful facilitation. And I think the method and process is a good one. It elicited all sorts of conversation. And it did get some of us who are firmly in our heads, out of our heads a little bit, which I think it is hopeful.

What are some of the tensions you experienced in doing performance-as-research with community members?

When we were talking about which groups to work with, we considered some of the people I had met when I was a policy analyst with the City of Hamilton. When I worked on a housing and homelessness plan for the city, I had met a group of women called the Women’s Housing Planning Collaborative. And I fell in love with these women! When we talked about the pilot, I said that I knew this amazing group of women. Why don’t we reach out to them? And so we did.

But I will say that I did feel apprehensive, and I told the team this. When you do community work, you build really strong relationships. I didn’t want to jeopardize my relationship with the women if we screwed things up. What if this process felt weird to them? Or if we all came in as a bunch of academics and propose this weird thing that made the women feel uncomfortable? I just worried that it could damage my relationship with them. Just those worlds colliding, my past community development world, with my present academic world, felt a bit hard for me. So, I did feel a bit nervous about sort of being positioned as the champion of performance-as-research, as this was a NEW process for me.

But it ended up being just fine. I wasn’t just fine, it was great! I think what helped is that we went to their space. We brought delicious food. And Catherine is really personable. She is really warm. She wandered in and just sort of disarmed people. She said, “Here’s what we’re doing. We kind of don’t know what were doing. We need you to help us figure out what were doing.”

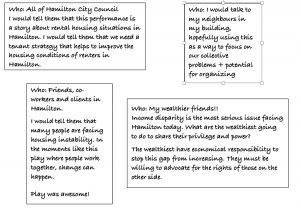

And I think the other thing is that we were part of the process. The research team participated in the story circle with the women. Catherine asked us to think about what housing in Hamilton would look like 10 years from now if the Women’s Housing Planning Collaborative’s advocacy work had worked. I was very pregnant at the time and I shared a pretty personal story. I think we needed to bring our personal stuff in that space to level the power imbalance that existed. I think those things helped.

What can Transforming Stories offer Social Work?

I teach the Introduction to Social Welfare course in the School of Social Work. I often invite the Women’s Housing Planning Collaborative Advisory to do guest lectures on lived experience advocacy. And those classes always go well. Students are always riveted. But one thing I did notice in the papers that they were writing, and in their reflections were the way they were taking up the women’s stories. They talked about the bravery of women and the tragedy of the women. Though I do feel it’s important for them to hear from folks with lived experience, the way it was being framed in their writing was pathologizing.

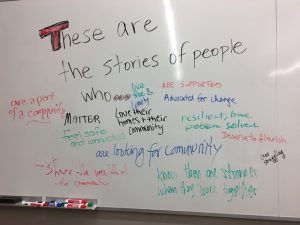

So, the first place the Women’s Housing Planning Collaborative Advisory performed was in a social work class. And I believe it shifted the way students understood the kinds of issues that the women were performing. They saw the women as individuals and human beings who lived that experience. What I think social work students got from their performance was a better understanding of the collective problems that we try to talk about in social work, which is so powerful. The way the women constructed the performance, and the way Catherine help them figure out how to convey their experiences using performance, really helped students understand people’s lived experiences of a much broader collective problem around income insecurity, housing and food insecurity. That’s huge!

What advice would you give a social worker who may want to engage in a performance-as-research project similar to Transforming Stories?

I would encourage people to do it. To actually explore more creative ways of engaging community. Not just consulting people, but engaging people and building relationships, longer-term relationships with people. I think I would encourage macro practitioners, even though we tend to be a fairly heady bunch, to immerse themselves in the process and be part of the process. I think that’s so important. Another piece of advice: be really careful about using this process. I do worry a bit that some people see arts-based methodologies as easy, or kind of flaky, or that anybody can do it. Our team has thought carefully about how this works. There is a lot of, particularly on Catherine’s part, solid thinking that went into how to do this ethically, and in a way that makes everybody feel good and excited. So, I just cautioned people not to use it cavalierly. To do it but to be really thoughtful about it.

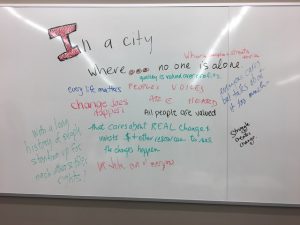

This project is adding different layers of voices to our vision of Hamilton. Hamilton is changing. There are people talking about change, and a lot of times it’s the same people, the politicians and that. So, we need to add new voices that they don’t get heard because they also have a stake in how Hamilton changes.

This project is adding different layers of voices to our vision of Hamilton. Hamilton is changing. There are people talking about change, and a lot of times it’s the same people, the politicians and that. So, we need to add new voices that they don’t get heard because they also have a stake in how Hamilton changes.