Our blog has been on a bit of a hiatus as we organize all the material that came out of our May 2nd performance of “When My Home Is Your Business.” We were pleased to see former TSDC performers, participants from the Social Planning and Research Council of Hamilton’s Displacements project, housing support workers, folks from the Community Legal Clinic and from church groups and community organizations, as well as a number of McMaster researchers, come out to the first performance of this new play. Our four performers did a great job of showing the audience what life is like in a building where tenants are trying to create a sense of neighbourliness, but where their needs and desires don’t seem count for much. They gave us a real feel for what it is like to try to build a sense of home when you are facing:

- intimidating Supers who blame tenants instead of making repairs

- elevators that don’t work reliably

- fire alarms constantly going off because of excessive humidity or dust from construction

- laundry rooms where half (or more) of the machines don’t work….

Despite all this, their performance offered the hope that people can work together to create a life where there is time and space for tenants to enjoy each other’s company and where despite it all, they can “stop and smell the flowers.”

But the story of “When My Home is Your Business” didn’t end with the performance. Discussions between audience members, the comments they left on index cards, their graffiti-like posts about what they thought life could be like in Hamilton if things changed for the better, all added to the story the play had started to tell.

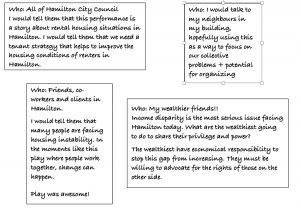

After the performance, we asked audience members to write anonymous messages on index cards to tell us who they would talk to about the performance and what they would tell them. The messages reflected the different connections people in the audience have and the different kinds of messages they might want to relay to different people in their lives.

After filling out the cards, the audience divided into four different groups of 10-12 to discuss what life might be like for the people in the play if things changed for the better. A lot of interesting ideas and potential new stories came out in these discussions. Some people thought that non-profit and co-op housing would give tenants more control over their living situations. Others suggested that tenant’s associations were the key to protecting their collective rights, and some proposed that housing should be considered a fundamental human right, not just a way to make a profit for private businesses. One group discussed the current rent strike in Stoney Creek and how actions like this create a memory of collective action.

Other audience members emphasized the importance of places where people can get together to get to know each other, other than just the elevator or the space in front of the mailboxes in their building. Still others pointed to the fact that not all the problems shown in the play are fundamentally problems of housing: people need adequate incomes to be able to build stable living situations, we need more accessible support services for people living with, or caring for others who live with, mental illness and addiction. We also discussed how the city needs to get behind affordable housing and how city services need not only to respond to phone calls promptly, but to actually do something about the complaints they receive in a timely manner.

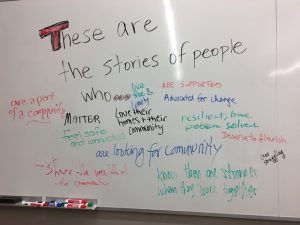

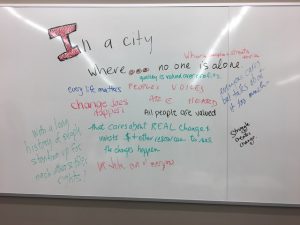

It was a lot to take in, but as people left the room, many of them shared their personal sense of what we should remember by summing up their views as “The story of people who… in a city where….”

Reading through all these responses, our research team was reminded of the way cultural theorist Michael Warner, in his essay “Publics and Counterpublics,” talks about what it takes to create public consciousness around an issue:

Public discourse says not only: “Let a public exist,” but: “Let it have this character, speak this way, see the world in this way.” It then goes out in search of confirmation that such a public exists, with greater or lesser success—success being further attempts to cite, circulate, and realize the world-understanding it articulates. Run it up the flagpole, and see who salutes. Put on a show, and see who shows up (82).

A lot of people showed up to see “When My Home Is Your Business” and their comments after the performance clearly indicated that they recognized the world portrayed in the play, could add to our description of it, could imagine how it might change. Thanks to the dedication of our performers, who spent 12 weeks working to collectively perform such a public vision, this play helped make visible some of the “world-making” that is already happening around public discussions of tenant’s situations in a rapidly gentrifying city. Audience response expanded on that understanding by using incidents in the play to circulate the world-understanding it articulated. What we have yet to see is, to take up Warner’s term, who else will “show up” and who else will “salute.”