… art’s “magic” was palpable. It was in the audience’s rapt silence — and its resounding applause.

Helene Vosters

Helene Vosters is an artist-scholar-activist and Project Coordinator at Transforming Stories, Driving Change. Her work focuses on the politics of social memory, and the role of performance and aesthetic practices in mobilizing engagement. With this post, Helene launches a conversation about the reflective post-performance “traces”—words and sketches—produced by audience members at the recent performance of Choose Your Destination, a Transforming Stories production performed by youth connected to Good Shepherd Youth Services.

trace:

- a surviving mark, sign or evidence of the former existence, influence, or action of some agent or event; vestige.

— Dictionary.com

In interviews previously posted on this blog, Transforming Stories, Driving Change co-Principal Investigators Chris Sinding and Catherine Graham speak about art’s “magic” (Chris) and the importance of audiences putting themselves in the picture by actively taking part in the collective task of imagining a better future (Catherine).

As socially-engaged arts-based researchers we are confident in the power of art to move those it reaches. At the recent performance of Choose Your Destination the “magic” was palpable. It was in the audience’s rapt silence—and its resounding applause. What can we do to nurture that magic—like one might tend to “Alice’s” metaphoric seeds from the Transforming Stories production When My Home Is Your Business? How can we extend the moment during which audiences are moved beyond the performance event itself? What activities might best invite audiences into a durational project of co-imagining a better Hamilton?

As we consider these questions we are cognizant that many Transforming Stories’ audience members are familiar with and actively engaged in sectors that work to address the issues that the performances raise—precarious housing, displacement, homelessness, issues confronting youth in Hamilton. In keeping with the project’s arts-based approach, we focus on how participation in creative acts of reflection might enhance existing practices and expand our collective capacity to co-imagine a better city, a better future.

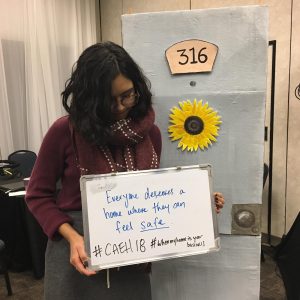

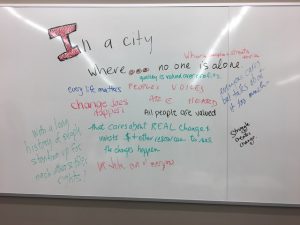

Traces I: Stories of people who…

An important element of post-performance activities is to provide the performers with some feedback and to give the audience an opportunity to become visible to one another, or as Transforming Stories co-investigator J. Adam Perry wrote in a previous post, “create public consciousness around an issue.” One of the first activities we often invite audiences to participate is the fill-in-the-blanks question that Jennie Vengris posed to the Choose Your Destination audience:

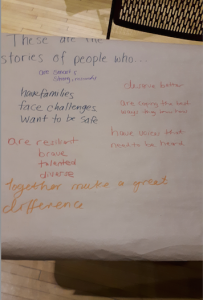

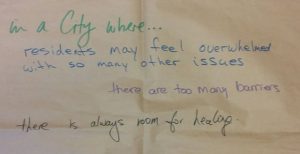

These are stories of people who…

in a city where…

The audience was seated “cabaret style” with four to five people around a table. Each table was covered in brown paper and strewn with art supplies. With this arrangement our intention was to facilitate both a sense of conviviality and a space for creative co-engagement. After asking audience members to move their refreshments aside Jennie invited them to avail themselves of the pens, pencils, and markers to record their responses to her questions. In looking at the two images above I am struck by how the coverings record so much more than the words of the participants. Captured in the relationship between the phrases and the variations in colour and handwriting, are the traces of the embodied relationship of the participants with one another.

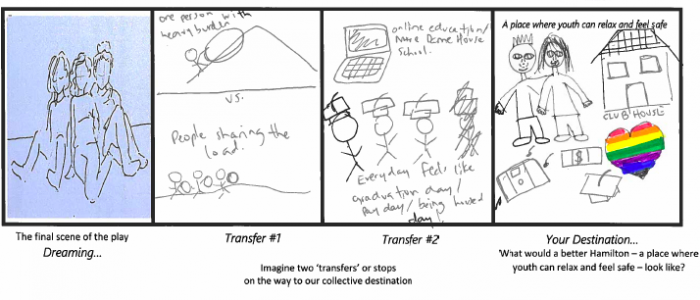

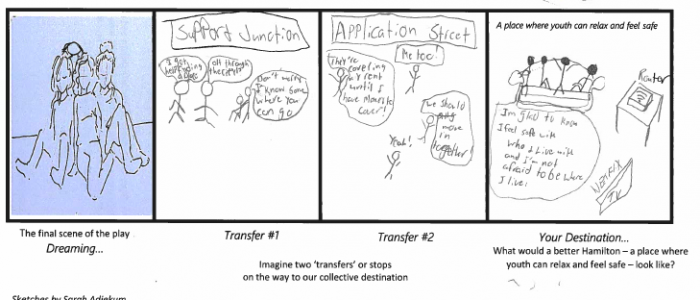

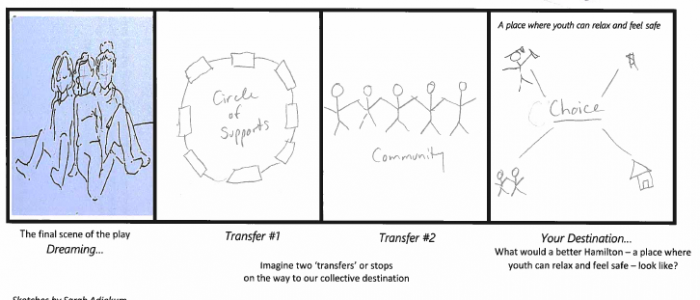

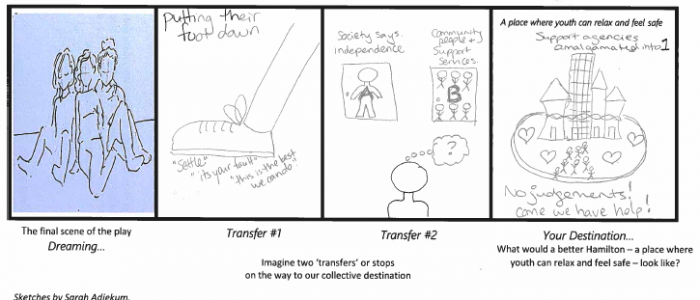

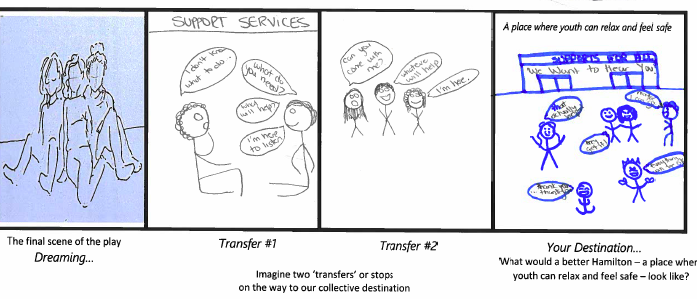

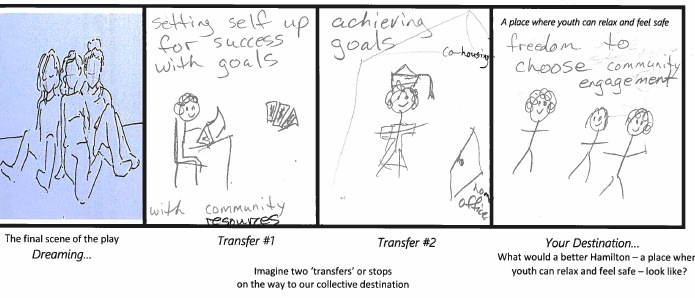

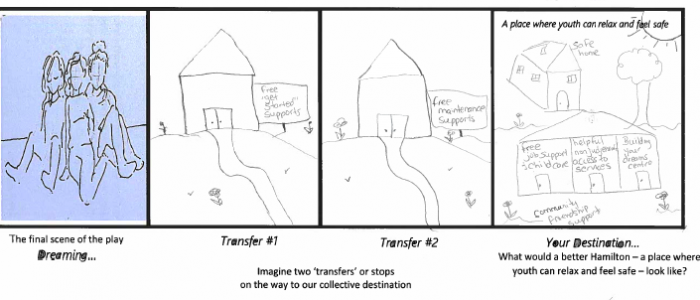

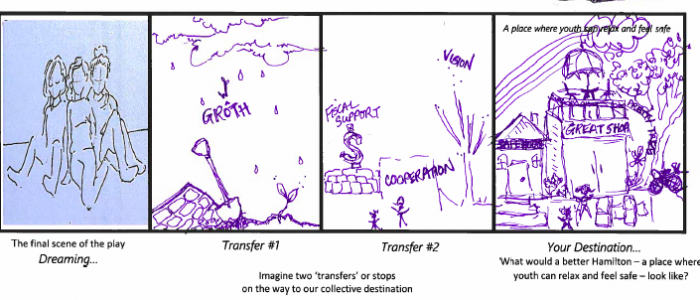

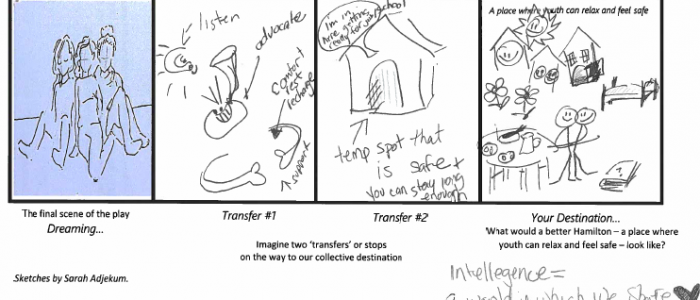

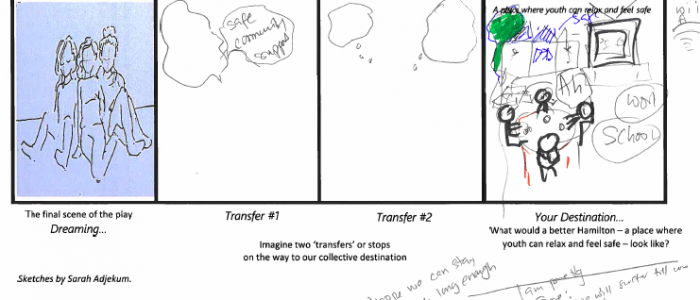

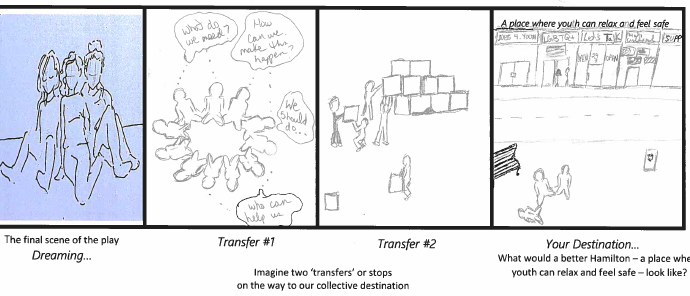

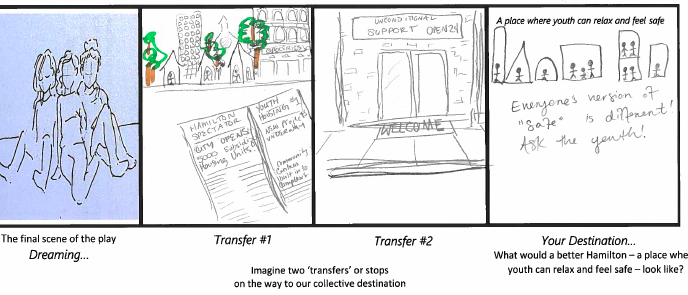

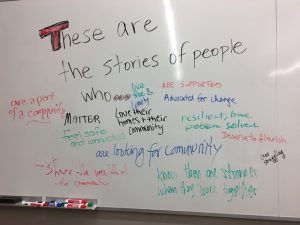

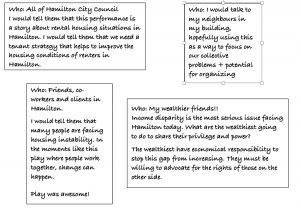

In our efforts to creatively engage audiences in co-imaginative acts of what Catherine refers to as “purposeful play” we are always exploring ways to expand our repertoire of post-performance activities. In addition to the these are stories of people who… in a city where… fill-in-the-blank exercise, we tried out a new post-performance activity that involved “storyboarding.” Inspired by Sarah Adjekum‘s sketches of the youth during the performance creation workshops, the exercise builds on the “live-storyboarding” process through which the play was developed wherein the youth created embodied “images” that were expanded into scenes and put together to create the play’s narrative arc.

For more on storyboarding, keep an eye out for our next post, “Traces II: Audience storyboards.”

… here’s a little slideshow preview…