Welcome to 2020! One purpose of the Transforming Stories, Driving Change blog is for members of the research team to reflect on experiences within the project and to make visible some of the methods we engage, and the questions we grapple with. We're excited to launch this new year (and new decade) with a guest post from a member of our TSDC research team, Elysée Nouvet. We hope you’ll join the conversation either by responding to a specific post, by writing a guest post, or by suggesting topics and participating in conversations.

Elysée Nouvet is a medical anthropologist specialized in cultural dimensions of pain and humanitarian healthcare ethics. She is an assistant professor at the University of Western Ontario, and also holds an appointment as Assistant professor (part-time) at McMaster. Dr. Nouvet has led and contributed to a number projects on contextual meanings and responses to suffering, as well as ‘beneficiary’ experiences of research and care. She holds a PhD in Social Anthropology from York (Toronto), and a Masters in Visual Anthropology from Goldsmiths College (U.K.).

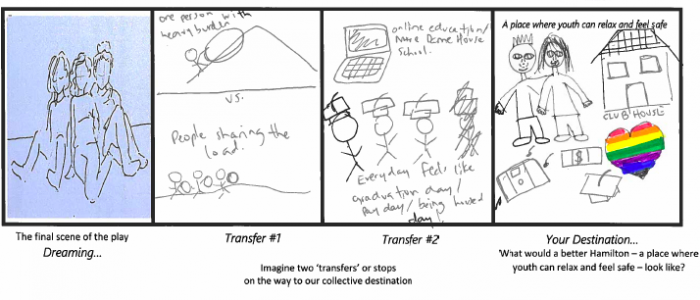

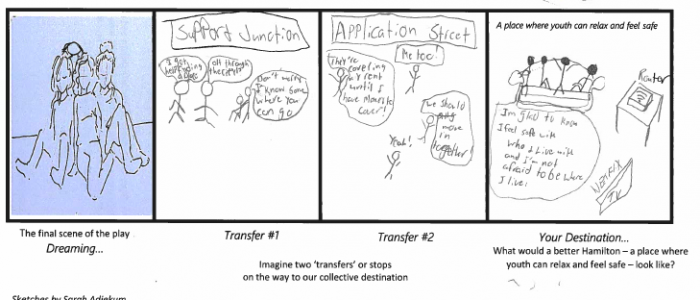

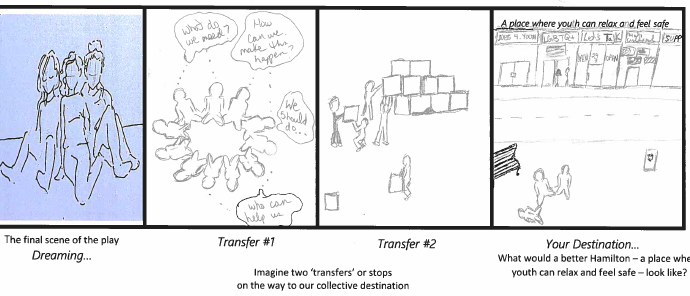

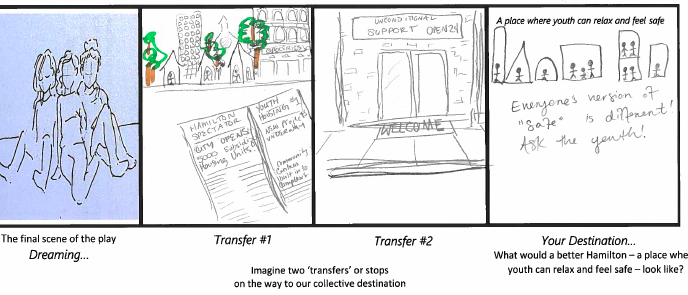

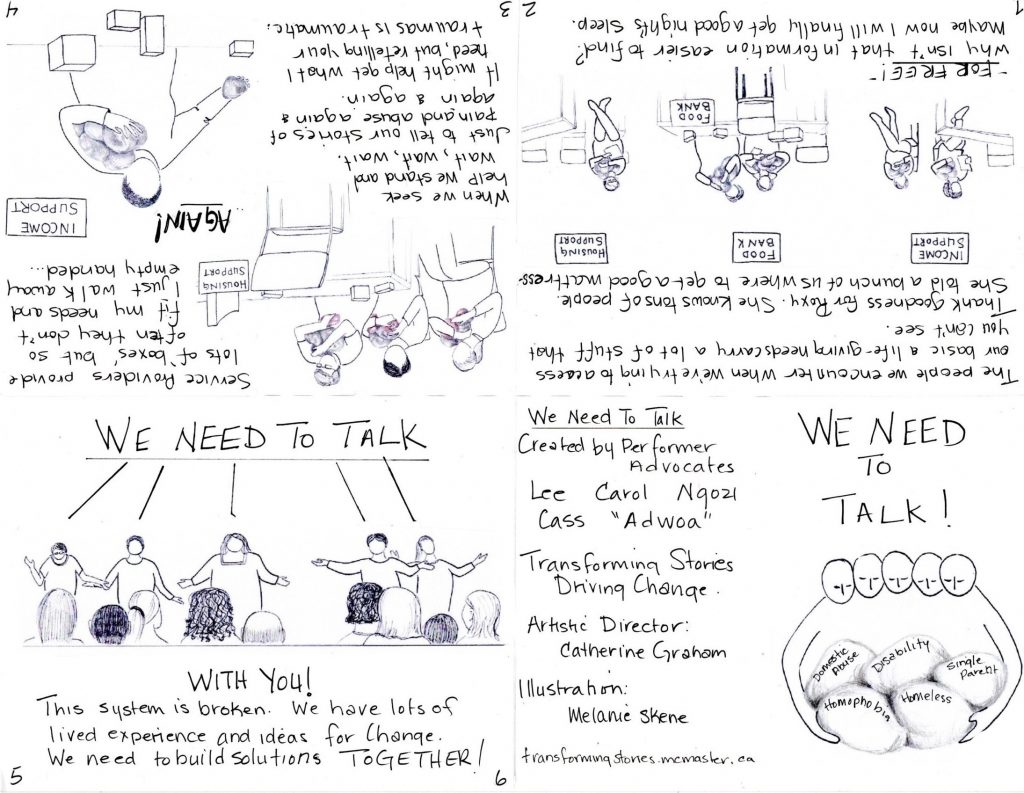

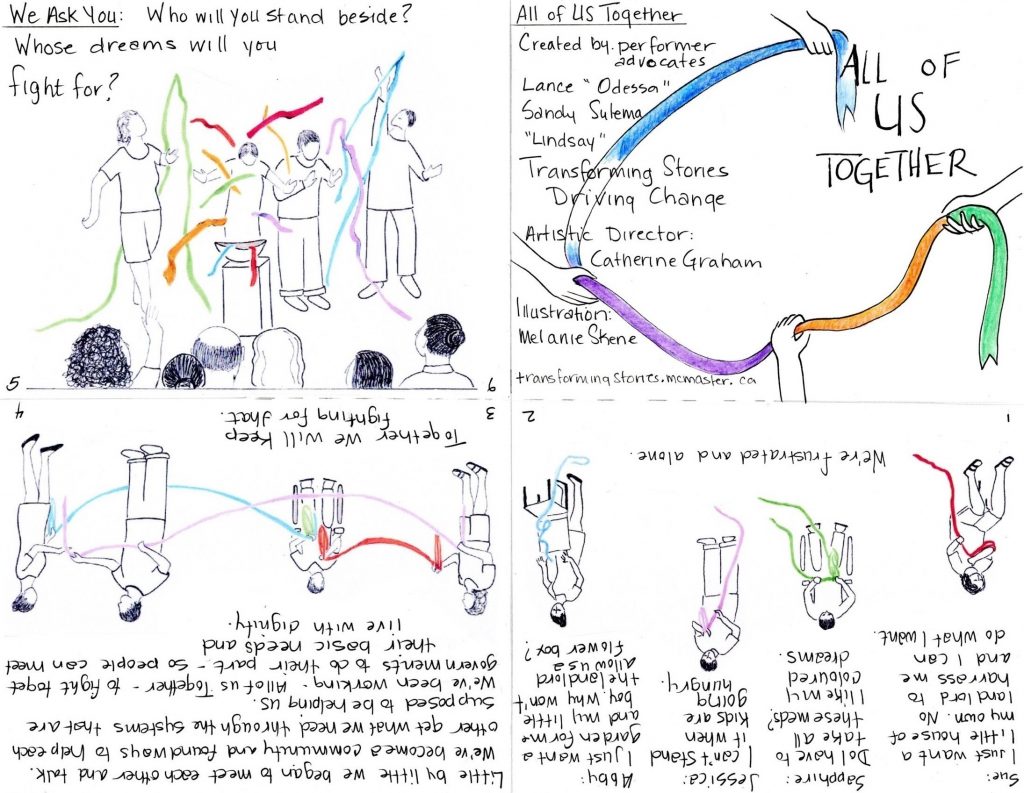

Winter 2017. We are a couple of months into a series of theatre-based workshops with women with lived experiences of precarious housing. These workshops are part of the “Transforming Hamilton Stories” project (2016-17), a pilot project that layed the foundation for TSDC.

Our research team has just received an additional small grant from McMaster, the home institution of the academics on the project. With the budget a little plumper, the research team decides it makes sense to: (1) increase hours for the artist supporting set design and prop creation for the workshop; and, (2) give women participants in the workshops an honoraria after each workshop. Workshops are 3-hour intense sessions in which group members work towards developing a presentation that took as its point of departure participants’ lived experiences of precarious housing. Up to that point, the provision of lunch, coffee, and bus tickets was what our budget permitted, but now we introduce an honorarium of $50 per workshop per participant.

A few weeks later, the matter of the honoraria comes up in a meeting. Was this going ok, to get people to sign off in the workshop and receive a little envelope of cash? Did we have a sense of how the provision of honoraria was understood and experienced by the workshop participants? We did not.

I volunteer that I feel all is going well. I have done my best to appear casual in getting participants to sign off on receiving their honoraria. As I speak though, I start to feel uncomfortable. Many conversations in the workshops at that point had centered on the women participants’ experiences of feeling routinely belittled, judged, and objectified when they tried to access health, food, and housing resources in the city. I had worked to appear casual, I realized, in an attempt to ensure provision of honoraria not echo those prior negative transactions. I had worried the one-way direction of honoraria, from the research team to workshop participants, also might underline socio-economic differences between the research team and participants so explicitly that this might disrupt any feelings of solidarity built thus far. And what about the fact that the honoraria was given to each participant in front of their peers?

As I sat in the meeting, I realized I had no idea how the women had felt. Had receiving the honoraria felt uncomfortable in any way to any of them? If yes, why? If not, why not?

The discussion in that meeting was the beginning of an unexpected point of enquiry for our research team. It flagged how under-examined the provision of honoraria in research actually is. What exactly does money in the form of honoraria do in the context of research?

Canada’s Tri-Council Policy II (2018), the Canadian reference guidelines for the conduct of research involving humans, does not mention honoraria. It has little to say about incentives and reimbursement, in fact. Article 3.2j states that any payment must be clearly explained to participants as part of their consent process. Article 3.1 of this same document cautions that “[b]ecause incentives are used to encourage participation in a research project, they are an important consideration in assessing voluntariness.” The guidelines recognize the centrality of context in determining whether an incentive offered is appropriate, or an unethical form of “undue inducement”: something that may push individuals to sign on as research participants when really, they would rather not.

Providing money to participants in any amounts that exceed the most basic participation-related expenses (e.g. bus tickets and parking fees in the context of Canadian research) is regarded by many as risky business. The primary concern is that “rewards” of research that are too tempting to refuse will undermine the core pillar of ethical research: Modern research ethics arose after World War II, and in response to the use of concentration camp prisoners by Nazi scientists for cruel and often fatal experiments. The 1947 Nuremberg Code, a key reference point for research ethics today, was named for the international trials that resulted in the conviction of many of the scientists involved in those experiments. The Nuremberg Code outlines 10 principles or conditions that must exist for research with human participants to be considered ethical and legal. Voluntary consent of the participant is the first of these. Freedom to decide whether or not to participate in research, the right to exercise this decision without being coerced, and the right to do so informed of all risks, is embedded in this core principle. It is against the dark legacy of disregard for all humans’ to chose whether or not they are willing to participate in research, that any research practice that potentially limits the freedom of an individual to refuse participation is closely scrutinized.

A related concern is that research participation motivated by self-interest is somehow morally problematic. This has never sat well with me. For one, researchers are not devoid of self-interest or expectations of personal gain. Moreover, and very troubling, is the implication that participants expecting or seeking benefits from research are somehow morally flawed. I have come across in my work the related suggestion that giving too much to participants risks corrupting otherwise “good” individuals. The unstated premise here is that money inevitably corrupts the research relationship. In this argument, the research that must be protected from the corrupting influences of money is idealized as operating outside of the financial economies of its key players (researchers and participants). The bottom line being that money corrupts. Money and voluntarism produce a tension, and risk staining research and research participation where these are idealized as extra-personal activities for the public good.

The Transforming Stories project team had obtained research ethics board approval for the provision of honoraria. We, as researchers, had zero moral distress about providing honoraria. On the contrary. We felt if our budget allowed it, it could be unethical not to do so. All the research team members were on salary when giving our afternoons to a workshop. We had access to institutional power, social recognition, and economic security the participants did not. We certainly could not see any justification for not transferring some of our newly acquired budget cash infusion to participants whose presence in and contributions to the workshop were as essential to its success as our own.

But there was the crux of the matter. Taking an inverse position that in the research ethics policies that warned payments to participants in the context of research could cause harm (e.g. be coercive and impede voluntariness), our research team had assumed the provision of honoraria might do good. In reality, we did not know. Maybe the provision of honorarium, though only $50 for an afternoon, was coercive given many participants were living on very low incomes. Maybe the honoraria did not feel right or good to participants. Did participants view it as a wage, a gift, or what? Did the participants have clear ideas in their minds about why the honoraria was provided, and whether this practice was ethical or not? How did the practice of providing honoraria play into workshop participants’ thinking about their role in the research project, and their relationship to the research team?

Sara Ahmed’s (2012) idea of performative and unperformative acts might help us think about this problem. A performative act recreates as it remakes the world. Ahmed differentiates from such acts unperformative acts. These are acts that assume the appearance of action, movement, but do nothing to shift power imbalances. Where the axis of ethical research aims to uphold a goal of social justice, figuring out how specific research practices contribute to or undermine that goal in specific research contexts is crucial.

The matter of honoraria was only one of the unexpected issues that arose through the work of this research group. We ended up conducting 10 interviews with participants in that first workshop. We asked them essentially: “What did the money [honoraria provided after workshops] mean to you?” We look forward to sharing some responses with you in an upcoming blog.

Works cited:

Ahmed, Sara (2012) On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Durham: Duke University Press.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, December 2018.

Wertheimer A, Miller F. G. (2008). “Payment for research participation: a coercive offer?” Journal of Medical Ethics 2008;34:389–392.

marginalization is an art that, when done well, feels more like magic. But even the best facilitators are not magicians. With this free online

marginalization is an art that, when done well, feels more like magic. But even the best facilitators are not magicians. With this free online