Our blog has been on a bit of a hiatus since this spring’s stunning performance of Choose Your Destination, a Transforming Stories, Driving Change (TSDC) production created with and performed by youth connected to Good Shepherd Youth Services. Despite the blog-break, members of the TSDC research team have been busy. We are currently in the process of gathering and organizing materials that came out of the performance. Sarah Adjekum has conducted interviews with Choose Your Destination’s youth participant-performers about their experience creating and performing the play. We are also seeking reflections from those who saw the play. In case you were in the audience and our email invitation hasn’t reached you, here’s the gist of the invitation:

Members of the TSDC research team would really appreciate the chance to learn more about how you perceived and experienced the play, your reflections following it, and what you took away from it. We invite you to share your views in one of these three ways:

- by completing an online survey (approximately 20 minutes): available till July 31

- through an individual phone or skype interview (30 minute): Please contact Helene Vosters at vostersh@mcmaster.ca to arrange date and time between June 25 and July 31

- by participating a focus group discussion (approximately 1 hour): Please contact Helene Vosters at vostersh@mcmaster.ca for date and time between June 25 and July 31

“The world’s a stage — for all”

The TSDC team has also been taking advantage of our post-production time to reflect on our experiences and to share some of our gleanings with an interdisciplinary range of scholars: In “The world’s a stage—for all,” an article by Sara Laux written for McMaster University’s “Brighter World” research website, Chris and Catherine discuss how the TSDC project’s interdisciplinary approach “uses the collaborative creation of a play to amplify the voices of people in Hamilton often marginalized in public debate.”

Here are a couple of my favorite quotes from the article:

From Chris:

“One of the things that’s striking to me about the work is how it plays with questions of standpoint or perspective […] There are many different ways that the performance opens up a new way of seeing or knowing, or disrupts an established way of seeing or knowing.”

… and Catherine:

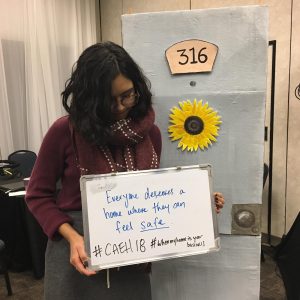

“In this age of populism, when too many media and political figures try to exploit the dissatisfaction of people who are feeling unheard, it is crucially important to create forums where marginalized voices can take their rightful place in public discussion […] We are working to create events where people from different social locations can speak to, not for or at, each other, and where nobody feels like they’ve been written out of the discussion before it even starts.”

“Between Performance & the Health/Social Sciences Seminar”

Four members of the TSDC research team also took part in a seminar hosted by the Canadian Association for Theatre Research as part of Congress 2019 at the University of British Columbia. Catherine co-organized the seminar (together with Julia Gray of the Bloorview Research Institute, University of Toronto), and Chris, Adam, and I (Helene) participated by sharing draft papers and engaging in pre-conference online discussions and as well as discussion at the conference.

The seminar invited papers that considered the various ways performance-based scholars and practitioners engage beyond our disciplinary borders with the health and social sciences. To give you a sense of what the TSDC research team brought the discussion (and, as always, please consider this an invitation to join the conversation!) below are brief excerpts from our (draft) papers and/or abstracts.

“Institutional ethics and performance-as-research: Toward relational accountability” — J. Adam Perry

In this article I argue that there is a bias toward status-quo forms of knowledge production in the name of institutional ethics that can both influence and destabilize possibilities for knowledge co-production in performative research. The traditional bioethical model from which current Research Ethics Boards (REBs) have sprung tends to characterize research participants as disembodied and autonomous selves, thus privileging privacy and individualism at the expense of community. These ethical assumptions are anathema to a performative approach to qualitative research that prioritizes the importance of belonging to and shared identification within a given community. In light of this contradiction, I make the case for an ethics of mutual recognition that disrupts the myth of a socially and culturally dis-embedded research subject. Such an ethics of mutual recognition would shift the moral point of view away from the protection of individual sovereignty and toward respect for a socially and narratively constructed self.

“Of billiard balls, flagpoles, and stones dropped in water: ‘Making a difference’ between performance and social science” — Chris Sinding

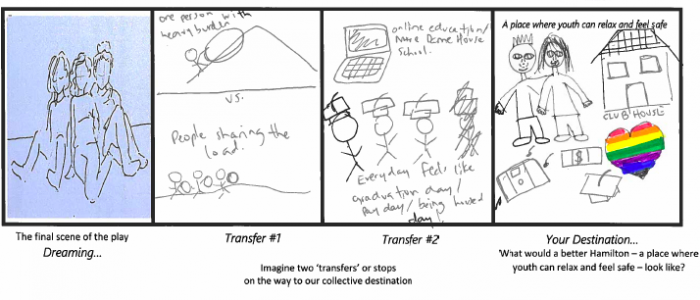

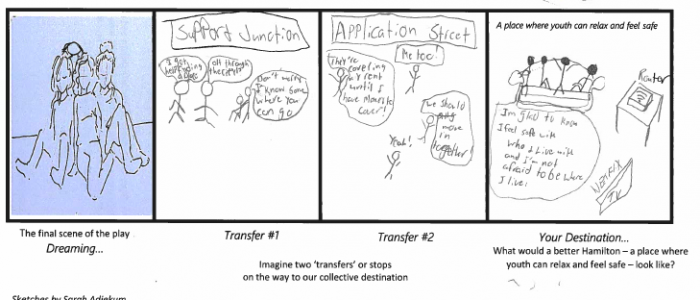

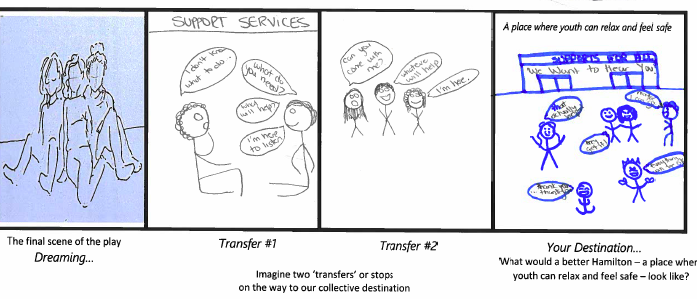

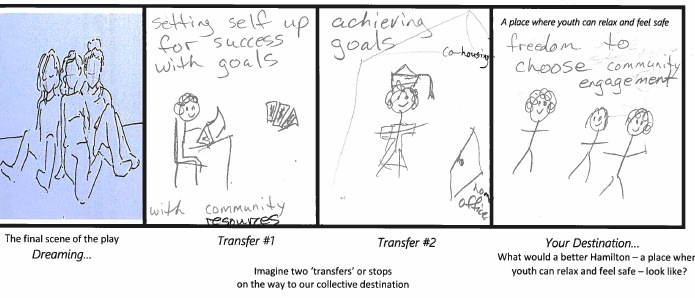

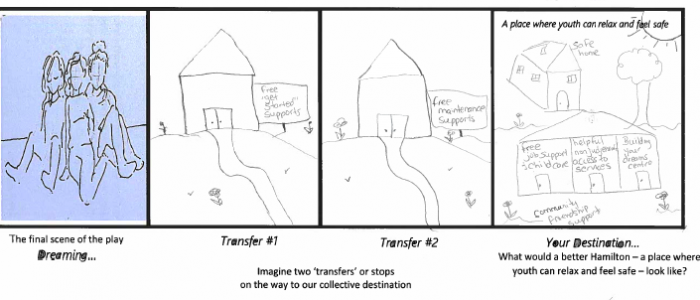

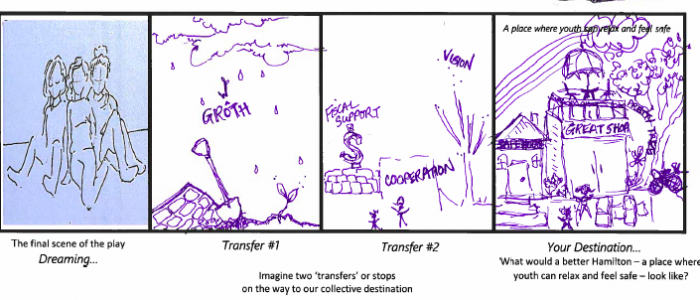

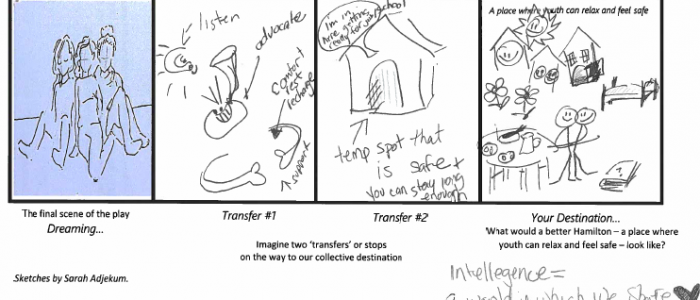

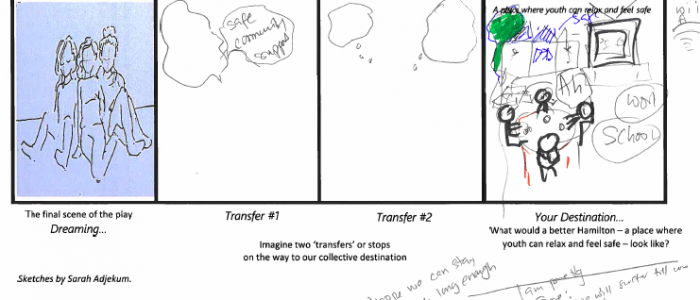

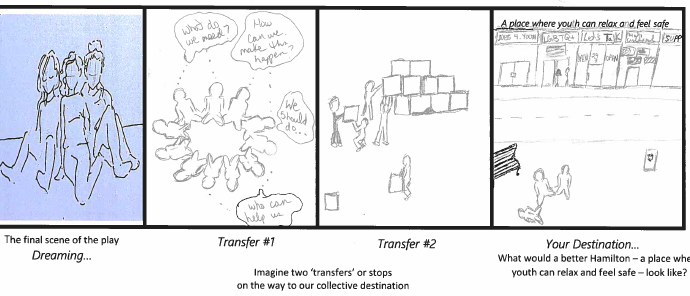

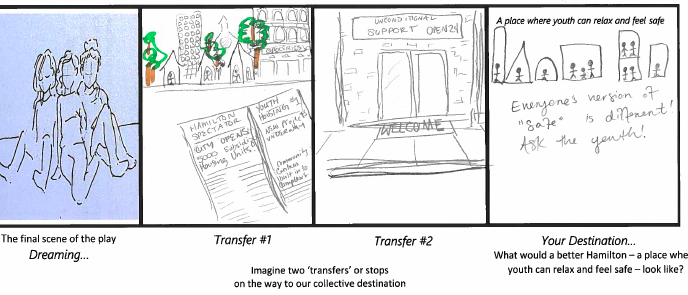

Transforming Stories, Driving Change uses performance to explore, and then show, patterns of exclusion experienced by particular communities in our city, and to present their desires and visions for a better world. Over the past two years community self-advocates, educators, social service workers and artists have come together to create stories and make theatre about living in inhospitable and precarious housing, dealing with the narrow mandates and inflexibility of social services, and navigating life under surveillance and threat.

In this presentation I (Chris) share my grappling (as some kind of social scientist) with the questions, what do these plays do in the world, and (how) can we know what they do? I review hopes and claims in the social work literature about ‘what art does’ (for service users, learners, researchers, teachers, practitioners, advocates, communities…) and describe my efforts to chart more thorough and expansive approaches to exploring the effects of arts-informed social science projects. Reflecting on TSDC, I describe how conversations with performance scholars, social work colleagues and community partners – and specifically, their metaphors for what we and the plays are and could or should be doing – helped reveal to me my own commitments and assumptions about change-making.

“‘In My World’: Metaphor, embodiment, and efficiencies in performance-based cross-sector collaborations” — Helene Vosters

Transforming Stories, Driving Change (TSDC) is an interdisciplinary project that uses performance to explore, and then show, how social exclusion affects particular communities in Hamilton, and how these communities are responding. The project brings together what Jan Cohen-Cruz calls “uncommon partners” (educators, theatre makers, arts and social science scholars, community self-advocates and social service workers)—individuals and communities who engage vocabularies particular to their unique disciplines and social locations. Catherine Graham (School of the Arts) and Chris Sinding (School of Social Work) are co-Principal Investigators on TSDC. In their conversations about the project Chris found herself prefacing her responses to some of Catherine’s ideas or analyses with, ‘in my world…’. Catherine drew attention to the phrase and it has since become a tool and a resource in the project. This paper is an exploration of the potential value of using ‘in my world’ as a conceptual framework for making processes of translation visible.

As a postdoctoral fellow with TSDC I have been struck by how drawing attention to phrase “in my world” foregrounds the presumption of what performance studies scholar Diana Taylor refers to as the (un)translatability of terms across various disciplinary, methodological, social, cultural and geopolitical locations. When communicating in coalitions of uncommon partners, how might parenthesizing our contributions with the phrase “in my world” help to bring out the productive potential of sites and moments of untranslatability as conduits for extending meaning-making across silo-ed academic disciplines and approaches, and social, geo-political, and cultural locations?

The Great Fanzinis pass a large soft stuffed ball from one person to another until each member of the Fanzini family has had the ball passed to them.

The Great Fanzinis pass a large soft stuffed ball from one person to another until each member of the Fanzini family has had the ball passed to them.

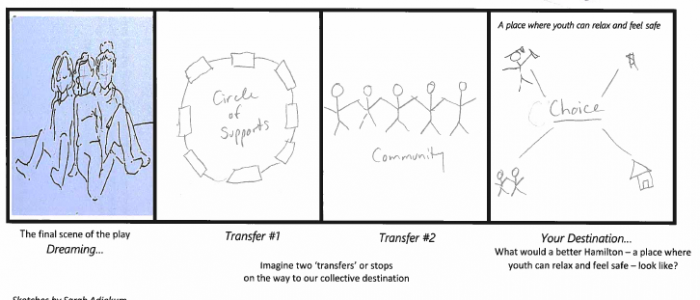

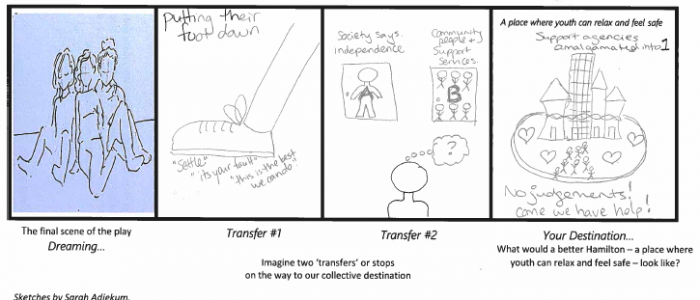

This project is adding different layers of voices to our vision of Hamilton. Hamilton is changing. There are people talking about change, and a lot of times it’s the same people, the politicians and that. So, we need to add new voices that they don’t get heard because they also have a stake in how Hamilton changes.

This project is adding different layers of voices to our vision of Hamilton. Hamilton is changing. There are people talking about change, and a lot of times it’s the same people, the politicians and that. So, we need to add new voices that they don’t get heard because they also have a stake in how Hamilton changes.