Robert Kroetsch died in a car accident today. Below is a reposting of Matthew Griffin’s September 12th 2009 post, “Influence without Anxiety”

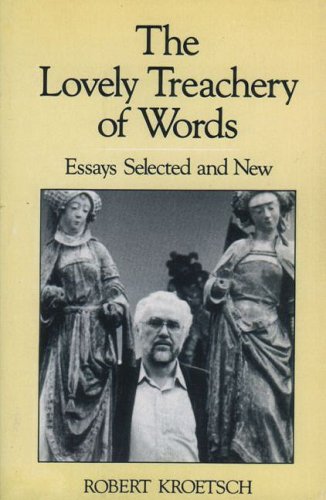

While much of the discussion on this blog has revolved around how Frye has been an influence on other critics, I think it also worth remembering his potent effect on novelists and poets as well. A reflection on what it is to write and to think about literature that has been formative for me is Robert Kroetsch’s essay, “Learning the Hero from Northrop Frye” (It’s perhaps easiest to find in The Lovely Treachery of Words: Essays Selected and New. Don Mills: Oxford, 1989. 151-162.) While we’d do well to remember an axiom from the Polemical Introduction, that the author “has a peculiar interest, but not a peculiar authority” as a critic of the author’s own work (CW 29: 7), Kroetsch writes that it was an encounter with Frye’s thought “that exhausted me into language” (151). He describes giving a seminar on Milton, using the just published Anatomy of Criticism as his “critical starting point,” only to be asked what the ideas therein were all about (154). Kroetsch describes his answer as follows:

I began, in answering that request, to talk about the hero, the nature of the hero, in literature, in the modern world, in my Canadian world, and in a way I haven’t stopped, and here, today, thirty years later, I’m still giving the report, though now Northrop Frye himself has become the hero under discussion, a peculiarly Canadian hero, in a modern world that has assigned to critics and theorists a hero’s many tasks. We live at a time when the young critic as tram faces the uncomfortable fate of becoming the old critic as god. (154)

Kroetsch’s essay marvels at just what influence Kroetsch has had on Canadian writing in particular, before finally concluding of Frye, that in “his collected criticism, he locates the poetry of our unlocatable poem. In talking about that poem, he becomes our epic poet. Grazie” (161).

Perhaps in this idea is fodder for our own reflections about how we might relax our own anxieties of influence, and look to see Frye’s impact upon writers beyond the sphere of criticism proper?