Frye in The Secular Scripture: “popular literature […] is neither better nor worse than elite literature, nor is it really a different kind of literature.” (CW 18, 23)

Monthly Archives: November 2010

Frye and Popular Art Forms

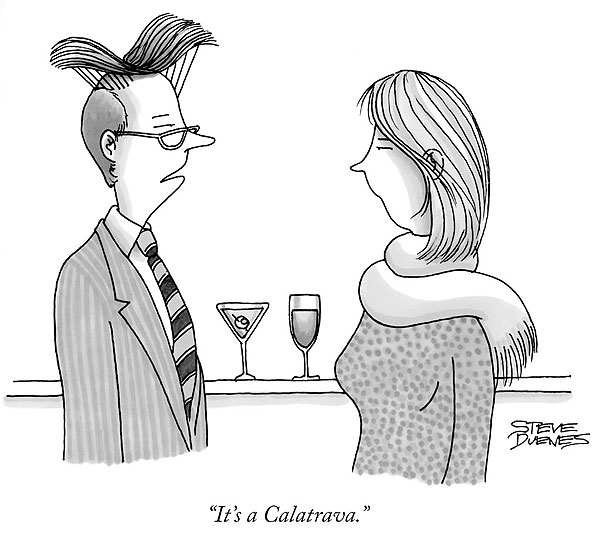

Further to yesterday’s comments on “Huxley and Orwell: Two Varieties of Dystopia”

Frye was always open to what he called “naïve” artistic forms—by which he meant primitive and popular. These included cartoons. In the Anatomy he writes:

The apparatus of ‘mass media’ and ‘audiovisual aids’ plays a similar allegorical role in contemporary education. Because of this basis in spectacle, naive allegory has its centre of gravity in the pictorial arts, and is most successful as art when recognized to be a form of occasional wit, as it is in the political cartoon.” And later, in his account of the pictorial thrust of the lyric, he says, “In such emblems as Herbert’s ‘The Altar’ and ‘Easter Wings,’ where the pictorial shape of the subject is suggested in the shape of the lines of the poem, we begin to approach the pictorial boundary of the lyric. The absorption of words by pictures, corresponding to the madrigal’s absorption of words by music, is picture-writing, of the kind most familiar to us in comic strips, captioned cartoons, posters, and other emblematic forms. A further stage of absorption is represented by Hogarth’s Rake’s Progress and similar narrative sequences of pictures, in the scroll pictures of the Orient, or in the novels in woodcuts that occasionally appear.

Frye’s work is replete with references to cartoons and comic strips. The New Yorker is his favourite source of the former, and from time to time he mentions cartoonists by name: David Low, Hugh Niblock, Saul Steinberg.

Otherwise, from the Anatomy:

The earliest extant European comedy, Aristophanes’ The Acharnians, contains the miles gloriosus or military braggart who is still going strong in Chaplin’s Great Dictator; the Joxer Daly of O’Casey’s Juno and the Paycock has the same character and dramatic function as the parasites of twenty-five hundred years ago, and the audiences of vaudeville, comic strips, and television programs still laugh at the jokes that were declared to be outworn at the opening of The Frogs.

The principle of repetition as the basis of humour both in Jonson’s sense and in ours is well known to the creators of comic strips, in which a character is established as a parasite, a glutton (often confined to one dish), or a shrew, and who begins to be funny after the point has been made every day for several months.

The essential element of plot in romance is adventure, which means that romance is naturally a sequential and processional form, hence we know it better from fiction than from drama. At its most naive it is an endless form in which a central character who never develops or ages goes through one adventure after another until the author himself collapses. We see this form in comic strips, where the central characters persist for years in a state of refrigerated deathlessness.

Humour, like attack, is founded on convention. The world of humour is a rigidly stylized world in which generous Scotchmen, obedient wives, beloved mothers-in-law, and professors with presence of mind are not permitted to exist. All humour demands agreement that certain things, such as a picture of a wife beating her husband in a comic strip, are conventionally funny. To introduce a comic strip in which a husband beats his wife would distress the reader, because it would mean learning a new convention.

Jonathan Swift

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3o2sfM05O4U

“A Description of the Morning”

Today is Jonathan Swift‘s birthday (1667-1745)

Frye in “The Imaginative and the Imaginary”:

The eighteenth century was the period in which this view of the imagination struggled with, and was finally defeated by, an opposed conception which came to power in the Romantic movement. At the beginning of the century we have Swift, for whom established authority in church and state was the only thing in human life strong enough to restrain the desperately irrational soul of man. In his day the conception of “melancholy” was out of fashion, but another ancient medical notion of “spirits” or “vapours” rising from the loins into the head was still going strong. For Swift, or at least for the purposes of Swift’s satire, all behavior that breaks down society is caused by an uprush either of digestive disturbances or of sexual excitement into the head. Swift’s chief target is the left-wing Protestantism which in the seventeenth century had carried religious melancholy to the point of replacing the authority of the church with private judgment and had made a virtue even of political rebellion. But he finds the same phenomena in the political tyrant who substitutes his own will for the social contract, or the poet who allows his emotions to take precedence over communication. “The very same principle,” he says, “that influences a bully to break the windows of a whore who has jilted him, naturally stirs up a great prince to raise mighty armies, and dream of nothing but sieges, battles and victories.” (CW 21, 430)

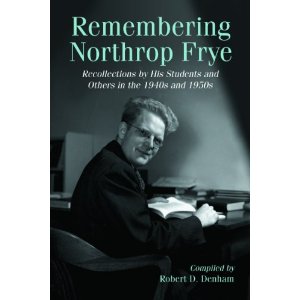

“Remembering Northrop Frye”

An email from McPharland Publishers today:

We are writing in order to let you know of our recent publication, Remembering Northrop Frye: Recollections by His Students and Others in the 1940s and 1950s by Robert D. Denham. Details about the book may be found in the following link: http://www.mcfarlandpub.com/book-2.php?id=978-0-7864-6069-4 . Should you wish to have additional information, please contact us and we’ll be glad to help.

Best,

Stephanie Nichols

Sales and Marketing

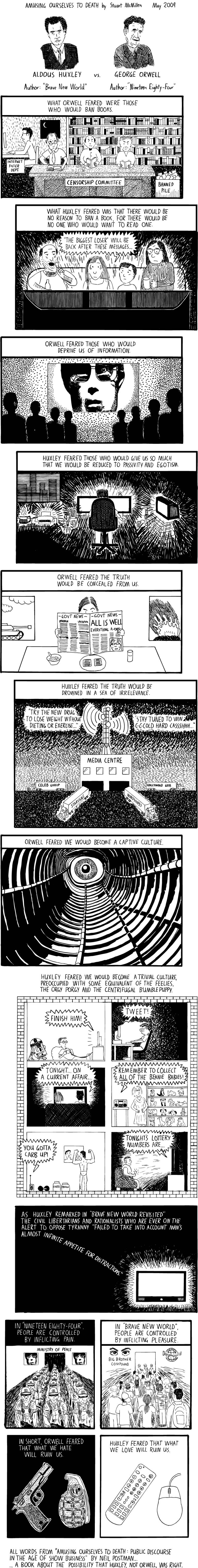

Huxley and Orwell: Two Varieties of Dystopia

Frye in “Varieties of Literary Utopia”:

A certain amont of claustrophobia enters this argument when it is realized, as it is from about 1850 on, that technology tends to unify the whole world. The conception of an isolated Utopia like that of More or Plato or Bacon gradually evaporates in the face of this fact. Out of this situation come two kinds of Utopian romance: the straight Utopia, which visualizes a world state assumed to be ideal, at least in comparison with what we have, and the Utopian satire or parody, which presents the same kind of social goal in terms of slavery, tyranny, or anarchy. Examples of the former in the literature in the last century include Bellamy’s Looking Backward, Morris’s News from Nowhere, and H.G. Wells’s A Modern Utopia. Wells is one of the few writers who have constructed both serious and satirical Utopias. Examples of the Utopian satire include Zamiatin’s We, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, and George Orwell’s 1984. There are other types of Utopian satire which we shall mention in a moment, but this particular kind is a product of modern technological society, its growing sense that the whole world is destined to the same social fate with no place to hide, and its increasing realization that technology moves toward the control not merely of nature but of the operation of the mind. (CW 27, 194-5)

Intellectual Segregation and the University of Toronto

I have previously written about the University of Toronto’s commitment to academic freedom and the influence of benefactors. According to the Memorandum of Agreement between the Peter and Melanie Munk Charitable Foundation and the University of Toronto, there will be a policy of implicit segregation at the University of Toronto. The agreement reads, in part:

The main entrance of the Heritage Mansion will be a formal entrance reserved only for senior staff and visitors to the School and the CIC. Usual and customary traffic for any occupants of any future developments adjoining the Heritage Mansion will be through one or more entrances on Devonshire Place.

In other words, the main entrance will be reserved for dignitaries and visitors to the school, as well as “senior staff.” Undergraduates, graduate students, post-doctoral students, regular faculty, sessional lecturers, administrative assistants, custodial staff, the general public, and taxpayers (who have contributed some 16 million of the 35 million dollar donation by the Munk Charitable Foundation) will all be required to use the back door to the Munk School of Global Affairs. This is not in the spirit of intellectual progress and public engagement.

The requirement of the Memorandum of Agreement also contradicts the University of Toronto’s Statement on Prohibited Discrimination and Harassment. Point 3 of the Statement reads: “In its Statement of Institutional Purpose the University affirms its dedication ‘to fostering an academic community in which the learning and scholarship of every member may flourish, with vigilant protection for individual human rights, and a resolute commitment to the principle of equal opportunity, equity and justice.’” It seems therefore that the Memorandum violates the Statement of Institutional Purpose insofar as not all members of the university community are afforded the same “opportunity” to enter through the “formal entrance reserved only for senior staff and visitors to the School and the CIC.”

Likewise, the Memorandum violates the university’s Human Rights Code, which “requires that employees of the University be accorded equal treatment without discrimination.” This “formal entrance” requires that all employees not be treated equally. Instead, the Memorandum states: “only senior staff and visitors to the School and CIC” will be permitted to enter this “formal entrance”; the rest of the academic community will have to use “one or more entrances on Devonshire Place.”

Will the university choose to violate the Statement of Institutional Purpose, the Human Rights Code, and the Statement on Prohibited Discrimination and Harassment, or will it revisit this part of the agreement? Whatever else the university hopes to accomplish here, it cannot allow blatant discrimination that amounts to segregation.

Frye Alert

Ovi Magazine has a post, “In Praise of Northrop Frye: A Giant of Literary Criticism,” here.

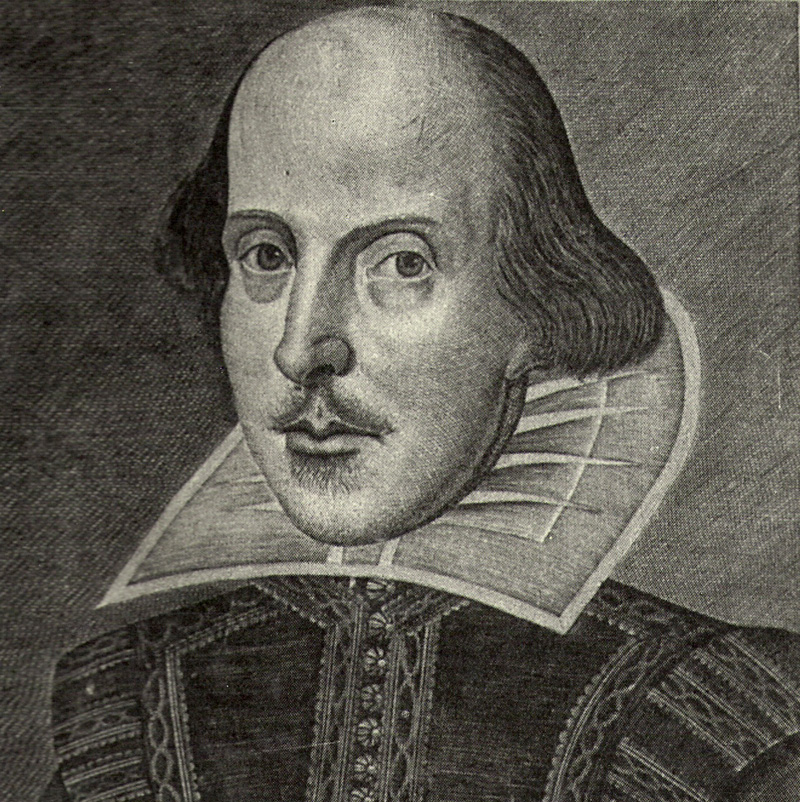

Shakespeare and Anne Hathaway

“A man who is clearly an idiot”

On this date in 1582 William Shakespeare and Anne Hathaway put up a bond for their pending marriage.

Frye in The Educated Imagination reminds us once again not to indulge in biographical fallacy:

We know nothing about Shakespeare except a signature or two, a few addresses, a will, a baptismal register, and the picture of a man who is clearly an idiot. We relate the poems and plays and novels we read and see, not to the men who wrote them, nor even directly to ourselves; we relate them to each other. Literature is the world that we try to build up and enter at the same time. (42)

Saturday Night at the Movies: “Metropolis”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zAuSEdPbqmo

It’s been an especially good week for the super-rich. They’ve seen record corporate profits while Republicans continue to lobby tirelessly to prevent the Bush tax cuts from expiring for the top percentile of earners. And all the while these happy few have been on the receiving end of hundreds of billions of bailout dollars to sustain the financial market they collapsed two years ago by way of a greed so rapacious that the market did not (as all true believers believe it must) “self-correct.” There’s also the trillions of dollars worth of “quantitative easing” now working its way through the system in a last ditch effort to keep the whole crazy scheme ricketing along like the Rube Goldberg contraption it really is. As economist Nouriel Roubini and others have noted, we now have socialism for the rich and capitalism for the poor.

The consequence is that tens of millions of people are chronically unemployed, stripped both of income and their remaining wealth: Ireland, Greece, and maybe Portugal are poised to go under, and perhaps take the rest of the world’s economy with them.

Don’t worry about the super-rich, however. In the U.S. alone, prior to the 2008 crash, they owned about 34% of the nation’s wealth; they now own about 38%. And while many millions of people must do without any income at all, the top 1% take in 25% of it. One assumes that they are doing so while curing cancer, resolving the suicidal impulses that drive global warming, and selflessly developing a free-of-charge vaccine for avian flu.

Tonight we’re running a restored version of Fritz Lang’s 1927 masterpiece Metropolis. Poetry, Auden says, changes nothing. And yet it still might serve as a reminder just how much everything can change because it ought to be changed.

Here’s Frye in conversation with David Cayley on being a “bourgeois liberal”:

Cayley: You’ve described yourself as a bourgeois liberal and even said that people who aren’t bourgeois liberals are still “in the trees.”

Frye: Or would be if they could.

Cayley: I don’t quite understand what you mean by that. This seems on the face of it a strange statement for a social democrat and a Methodist and a populist to make.

Frye: Well, the bourgeois liberal to me is the nearest analogy I can think of to a man who is sufficiently left alone by the structure of authority in his society to develop his individuality. Because he’s a liberal, he doesn’t become an anarchist, that is, he doesn’t grab all the money and corner all the property in sight. He’s a person who can relate to other people. He doesn’t withdraw from society or become a mass man.

Cayley: So the emphasis is not the same as Marx gives the term “bourgeoisie” when he uses it to signify the hegemony of a certain class?

Frye: The bourgeois liberal is capable of seeing himself as having a certain position in society. He’s also capable of seeing something that that situation puts him into. You can’t avoid being conditioned, but you can to some extent become aware of your conditioning. (CW 24, 971)

The rest of the movie after the jump.

Jimi Hendrix

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rf-Mtd2A1DI

A lovely 1967 performance of “The Wind Cries Mary”

Today is Jimi Hendrix‘ birthday (1942-1970).