Kalle Lasn, founder of Adbusters, interviewed on CNN five years ago. The smug, eye-rolling awfulness of the expendable, interchangeable, assembly-line interviewer is reason enough to watch it.

Mattathias Schwartz has an article on “the origins and future of Occupy Wall Street” in the New Yorker. I knew about its Canadian roots at Adbusters, based in Vancouver, but didn’t realize the extent to which it got the movement going in very short order, demonstrating the generational leap in the use of real-time social media, which sidesteps altogether the mindlessness of corporate “old media,” evident in the clip above. Schwartz’ article also has a good look at the on-the-ground reality of “horizontal” rather than “vertical” organizing principles, and introduces a number of people who are crucial “facilitators” of the movement, but are otherwise unknown, as they’d want it to be. It therefore also provides a surprisingly moving account of the difficult effort to maintain anarchist principles without collapsing into anarchy.

An excerpt:

This is how Occupy Wall Street began: as one of many half-formed plans circulating through conversations between [Kalle] Lasn and [Adbusters editor Micah ]White, who lives in Berkeley and has not seen Lasn in person for more than four years. Neither can recall who first had the idea of trying to take over lower Manhattan. In early June, Adbusters sent an e-mail to subscribers stating that “America needs its own Tahrir.” The next day, White wrote to Lasn that he was “very excited about the Occupy Wall Street meme. . . . I think we should make this happen.” He proposed three possible Web sites: OccupyWallStreet.org, AcampadaWallStreet.org, and TakeWallStreet.org.

“No. 1 is best,” Lasn replied, on June 9th. That evening, he registered OccupyWallStreet.org.

*

*

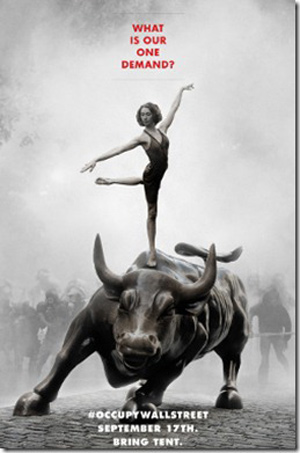

This spring, the magazine was pushing boycotts of Starbucks (for driving out local businesses) and the Huffington Post (for exploiting citizen journalists). Then, in early June, the art department designed a poster showing a ballerina poised on the “Charging Bull” sculpture, near Wall Street. Lasn had thought of the image late at night while walking his German shepherd, Taka: “the juxtaposition of the capitalist dynamism of the bull,” he remembers, “with the Zen stillness of the ballerina.” In the background, protesters were emerging from a cloud of tear gas. The violence had a highly aestheticized, dreamlike quality—Adbusters’ signature. “What is our one demand?” the poster asked. “Occupy Wall Street. Bring tent.”

*

White watched as the e-mail’s proposal raced around Twitter and Reddit. “Normal campaigns are lots of drudgery and not much payoff, like rolling a snowball up a hill,” he said. “This was the reverse.” Fifteen minutes after Lasn sent the e-mail, Justine Tunney, a twenty-six-year-old in Philadelphia, read it on her RSS feed. The next day, she registered OccupyWallSt.org, which soon became the movement’s online headquarters. She began operating the site with a small team, most of whose members were, like her, transgender anarchists. (They jokingly call themselves Trans World Order.)

Encouraged by the quick online response, White connected with New Yorkers Against Budget Cuts, which had previously organized an occupation-style action, called Bloombergville, and was already planning an August 2nd rally at the “Charging Bull” to protest cuts that would likely result from the federal debt crisis. They agreed to join forces, and N.Y.A.B.C. said that it would devote part of its upcoming rally to planning for the September 17th occupation.