Here. Terrifying, soul-rending.

Monthly Archives: May 2011

Rameses the Great and “Literal” Meaning in the Bible

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h0MrvvW_kiY

“New evidence linking Rameses and Moses”

A little synchronicity: Rameses II the Great became pharaoh of Egypt on this date in 1279 BCE; Frye makes reference to him in “Symbolism in the Bible” to correct misapprehension about the “literal” meaning of the Bible. The Bible records not history, but a typological manifestation of concern:

[W]hen John the Baptist is asked if he is Elijah, he says that he is not. Now, there is no difficulty there, unless you want to foul yourselves up over a totally impossible conception of literal meaning: reincarnation in its literal there’s-that-man-again form is not a functional doctrine in the Bible. At the same time, metaphorically, which is one of the meanings of “spiritually” in the New Testament, John the Baptist is a reborn Elijah just as Nero is a reborn Nebuchadnezzar or Rameses II. So, it is not surprising that the great scene of the Transfiguration in the Gospels should show Jesus as flanked by Moses on one side and Elijah on the other — that is, the Word of God with the law and the prophets supporting him. Again, that has its demonic parody in the figure of the crucified Christ with the two theives flanking him on either side. (CW 13, 499-50)

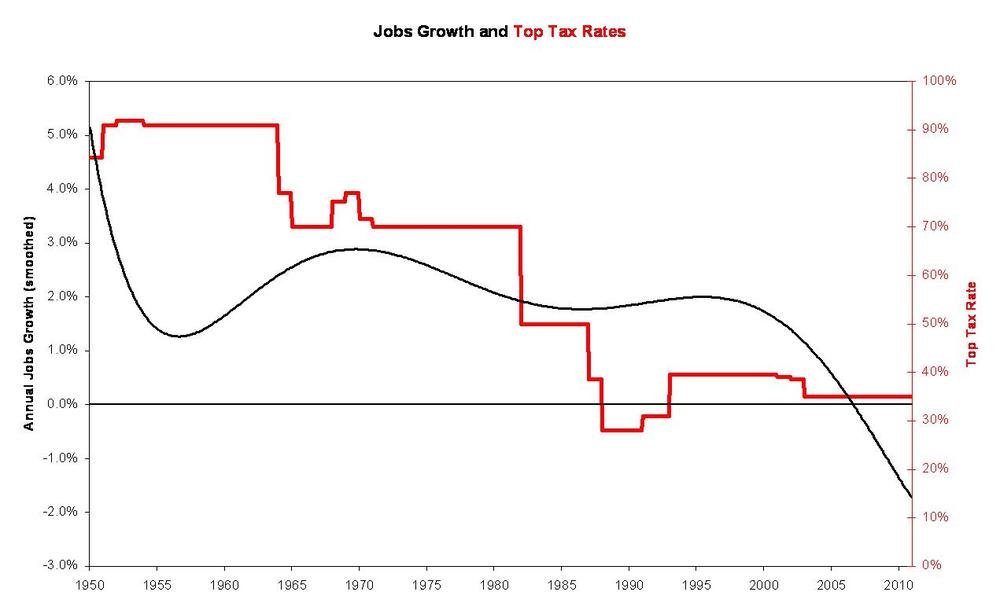

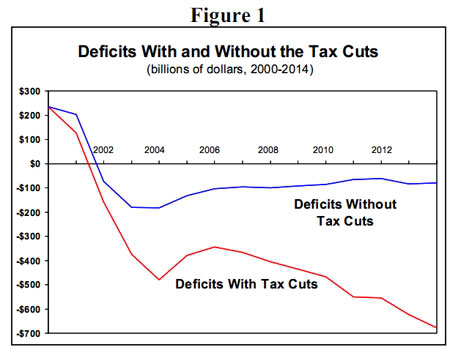

Taxes, Jobs, Deficits

Diminishing return: lower taxes result in lower job growth in the long run — note the nosedive after the Bush tax cuts in 2000.

Uh oh: the larger the high-end tax cuts, the larger the deficit — note the explosive growth of the deficit after the Bush tax cuts of 2000 (red line). Note also that if the Bush tax cuts were repealed, the deficit drifts easily into manageable territory (blue line).

If we’re talking bottom line, here it is: lower taxes have demonstrably meant diminishing job creation (not to mention devastated social services) and larger deficits. We know that’s not been the conventional wisdom since the storied days of Ronald Reagan in the misty past of thirty years ago, but it is the reality.

Even after eight years of Bushonomics that have crippled American fiscal policy, the current government of Canada is about to more or less repeat the same mistakes. Social and government services will be cut in the name of “austerity.” Welfare, meanwhile, is now strictly for corporations in the form of still more tax cuts, the purchase of tens of billions worth of American jet interceptors, and a massive payday for developers with the building of new prisons at a time when crime rates are down sharply after declining for a decade.

Frye on False Literalism: “The Bible is explicitly antireferential in structure”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cihcMqBgmPs

Picking up again on our examination of the relation of Christian fundamentalism to right wing politics, here’s Frye in “The Double Mirror” on the false literalism of fundamentalists. (It’s a long excerpt, but it leads up to the last paragraph that makes it worth the effort.)

The traditional view of the Bible, as we all know, has been that it must be regarded as “literally” true. This view of “literal” meaning assumes that the Bible is a transparent medium of words conveying a “true” picture of historical events and conceptual doctrines. It is a vehicle of “revelation,” and revelation means that something objective, behind the words, is being conveyed directly to the reader. It is also an “inspired” book, and inspiration means that its authors were, so to speak, holy tape-recorders, writing at the dictation of an external spiritual power.

This view is based on an assumption about verbal truth that needs examining. One direction is centripetal, where we establish a context out of the words read; the other is centrifugal, where we try to remember what the words mean in the world outside. Sometimes the external meanings take on a structure descriptive or nonliterary. Here the question of “truth” arises: the structure is “true” if it is a satisfactory counterpart to the external structure to it is parallel. If there is no external counterpart, the structure is said to be literary or imaginative, existing for its own sake, and hence often considered a form of permissible lying. If the Bible is “true,” tradition says, it must be a nonliterary counterpart of something outside it. It is, as Derrida would say, an absence invoking a presence, the “word of God” as a book pointing to “the word of God” as speaking presence in history. It is curious that although this view of Biblical meaning was intended to exalt the Bible as a uniquely sacrosanct book, it in fact turned it into a servomechanism, its words conveying truths or events that by definition were more important than the words were. The written Bible, this view is really saying, is a concession to time: as Socrates says of writing in the Phaedrus, it is intended only to call to mind something that has passed away from presence. The real basis of the Bible, for all theologians down to Karl Barth at least, is the presence represented by the phrase “God speaks.”

We have next to try to understand how this view arose. In a primitive society (whatever we mean by primitive), there is a largely undifferentiated body of verbal material, held together by the sense of its importance to that society. This material tells the society what the society needs to know about its history, religion, class structure, and law. As society becomes more complex, these elements become more distinct and autonomous. Legend and saga develop into history; stories, sacred or secular, develop into literature; a mixture of practical knowledge and magic develops into science. Society struggles to contain these elements within its overriding concerns, and tries to impose on them a structure of authority that will keep them unified, as Christianity did in medieval times. About two generations ago there was a fashion for crying up the Middle Ages as a golden age in which all aspects of culture were unified by common sentiments and beliefs. Similar developments, with a similar appeal, are taking place today in Marxist countries.

New to the Library: Frye on Islam and the Koran, Pt 2

Frye at the Movies: “Detective Story”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O8NnjbzsTP8

Frye refers to this movie in his 1952 diary as a “sardonic masterpiece.” Detective stories generally were a source of almost guiltless pleasure for him (even putting aside their value in studying popular and primitive archetypes), and he made reference to them often. However, this personal account in his 1942 diary of reading them is easily the most charming:

I don’t think that I have either a highbrow or a lowbrow pose about detective stories, but I don’t really quite understand why I like reading them. I read them partly for the sake of the overtones. I’m not a connoisseur of them: I can never guess what the hell’s up when the detective pulls out a watch and shouts: “My God, we may yet be in time!”, shoves the narrator and half the country’s police force into a taxi, dashes madly across town and finds the girl I’d placidly thought was the heroine all equipped with a blunt instrument & an animal snarl. I’m always led by the nose up the garden path in search of a false clue, and I never notice inconsistencies. And I always get let down when I find out who dun it. As I say, I like overtones. A good style, some traces of wit & characterization, a sense of atmosphere, and a lot of the professional intricacies of the game can go to hell. Yet I want a good novel in that particular convention & no other. The answer is, I think, that I’m naturally a slow & reflective reader, & make copious marginalia. In the detective story I live for a moment in the pure present: I’m passively pulled along from stimulus to stimulus, and, ignorant & idle as that doubtless is, I’m fascinated by it. Yet I seldom finish without disappointment. (CW 8, 15)

Frye Quote of the Day: Putting “the watchdog of consciousness to sleep”

Saman Mohammdi cites Frye to characterize the rhetorical abuse of language in current political discourse. The entire article is here.

Canadian literary critic Northrop Frye said that words convey cultural and societal myths and make particular ideological beliefs hold sway over people’s minds. In his book Words with Power Frye noted the power of language to establish certain myths in a society and enable those myths to be passed on to future generations, writing:

Myth loses its ideological function except for what is taken over and adapted by logos . Myths that are no longer believed, no longer connected with cult or ritual, become purely literary; myths that retain a special status in society are translated into logos language, and are taught and learned in that form. (2).

The neoconservatives and other cliques who work for Washington’s hidden establishment have exploited the power of myth and the dark power of words to pursue criminal goals both inside America and in the Middle East. But all this is well known by political spin doctors and directors of political campaigns. Barack Obama would never have been elected President if he did not cunningly exploit the power of rhetoric and repeat universal words like “hope” and “change” to hypnotize voters and get them to think positively about him. He is slick, but not wise. A wise man would never have chosen to be the spokesperson for America’s plutocratic elite and carry out their criminal agenda.

Frye wrote about the politician’s misuse of rhetoric to captivate the crowd and put it in a state of submissiveness. He said:

When the rhetorical occasion narrows down from the historical to the immediate, as at rallies and pep talks, we begin to see features in rhetoric that account for the suspicion, even contempt, with which it was regarded so often by Plato and Aristotle. Let us take a rhetorical situation at its worst. In intensive rhetoric with a short-term aim, there is a deliberate attempt to put the watchdog of consciousness to sleep, and the steady battering of consciousness becomes hypnotic, as the metaphor of “swaying” an audience suggests. A repetition of cliché phrases is designed to bring about a form of dissociation. The dead end of all this is the semi-autonomous monster called the mob, of which the speaker is now the shrieking head. For a mob the kind of independent judgement appealed by dialectic is an act of open defiance, and is normally treated as such. (3).

Obama’s mob, like Bush’s mob, and Palin-McCain’s mob, have no idea who or what they are supporting because they want to cheer on their leaders instead of ask serious questions about their background, philosophy, and political programs. They are totally identified with them. When someone points out to them that they have been betrayed by the entire political establishment, republican and democrat alike, they half-agree, calling the other side evil, and continue to worship their chosen leader. They view anybody who questions the word or morality of their leader as a threat to their existence. Rather than engage in a debate with people who have a different opinion they resort to all sorts of childish tactics like calling them a “conspiracy theorist,” an “extremist,” and even a “traitor” without any evidence to support their statements. They don’t have any idea what these words were designed for but they repeat them anyway to silence critics and shut down debate.

TGIF: Taco Town

SNL commercial parodies are always worth seeing. This is one of the best. Taco Town is us, and it doesn’t show much sign of no longer being us.

You can watch it here.

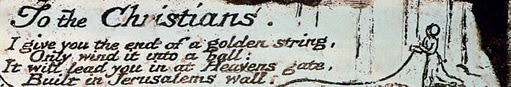

William Blake: “It is an easy thing to rejoice in the tents of prosperity”

Further to Michael’s previous posts, “What Would Jesus Defund?”, here’s William Blake, the man Frye says taught him everything he knows, on the everyday indifference to the poor in The Four Zoas, “Night the Seventh,” ll. 111-29:

It is an easy thing to triumph in the summer’s sun

And in the vintage and to sing on the waggon loaded with corn.

It is an easy thing to talk of patience to the afflicted,

To speak the laws of prudence to the houseless wanderer,

To listen to the hungry raven’s cry in wintry season

When the red blood is fill’d with wine and with the marrow of lambs.

It is an easy thing to laugh at wrathful elements,

To hear the dog howl at the wintry door, the ox in the slaughter house moan;

To see a god on every wind and a blessing on every blast;

To hear sounds of love in the thunder storm that destroys our enemies’ house;

To rejoice in the blight that covers his field, and the sickness that cuts off his children,

While our olive and vine sing and laugh round our door, and our children bring fruits and flowers.

Then the groan and the dolor are quite forgotten, and the slave grinding at the mill,

And the captive in chains, and the poor in the prison, and the soldier in the field

When the shatter’d bone hath laid him groaning among the happier dead.

It is an easy thing to rejoice in the tents of prosperity:

Thus could I sing and thus rejoice: ‘but it is not so with me.’

‘Compel the poor to live upon a crust of bread, by soft mild arts.

Smile when they frown, frown when they smile; and when a man looks pale

With labour and abstinence, say he looks healthy and happy;

And when his children sicken, let them die; there are enough

Born, even too many, and our earth will be overrun

Without these arts. If you would make the poor live with temper,

With pomp give every crust of bread you give; with gracious cunning

Magnify small gifts; reduce the man to want a gift, and then give with pomp.

Say he smiles if you hear him sigh. If pale, say he is ruddy.

Preach temperance: say he is overgorg’d and drowns his wit

In strong drink, though you know that bread and water are all

He can afford. Flatter his wife, pity his children, till we can

Reduce all to our will, as spaniels are taught with art.’

Samuel Pepys

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dn6E_4g4UAw

From Peter Ackroyd’s documentary series, London: A Biography (based upon the terrific book by the same name), Pepys describes the Great Fire of London, 1666

Yesterday was the anniversary of Samuel Pepys‘s death (1603-1703). Frye, in his 1942 diary, makes some observations on perhaps the most famous diarist in the language. Bob Denham’s remarks in the Introduction to the Diaries volume offers commentary that deserves to be included:

Frye placed a high priority on privacy, and after he became a name, his secretary Jane Widdicombe did succeed in protecting him from most of the countless potential invasions of that privacy. He was fond of telling interviewers that he had unconsciously arranged his life to be without incident, the result being, he claimed, that no biographer would have the slightest interest in him as a subject. John Ayre’s biography is, of course, evidence to the contrary. And however much we might like to agree in theory with Eliot’s principle that there is a difference between the man who suffers and the mind which creates, in practice the principle is very difficult to maintain. When one becomes a public figure, there is a natural curiosity on the part of the public to learn about his or her life. Frye was also fond of insisting that his life was his published work, just as he was fond of quoting Montaigne’s remark that his life was consubstantial with his book. One can understand what he meant by that, and yet this opposition between life and work, at the deepest level, cannot finally be sustained, as Michael Dolzani has shown.[14]

Frye is aware, of course, that whatever aims the diarist might have, what will emerge from all diaries is necessarily self-revelation. The self-revelation may be minimal, but it is there. The absence of sufficient self-revelation is what worried Frye about Samuel Pepys’s Diary:

I’ve been reading in Pepys, to avoid work. I can’t understand him at all. I mean, the notion that he tells us more about himself & gives us a more intimate glimpse of the age than anyone else doesn’t strike me. I find him more elusive and baffling than anyone. He has a curious combination of apparent frankness and real reticence that masks him more than anything else could do. One could call it a “typically English” trait, but there were no typical Englishmen then and Montaigne performs a miracle of disguise in a far subtler & bigger way. Pepys is not exactly conventional: he is socially disciplined. He tells us nothing about himself except what is generic. His gaze is directed out: he tells us where he has been & what he has done, but there is no reflection, far less self-analysis. The most important problem of the Diary & of related works is whether this absence of reflection is an accident, an individual design, or simply impossible to anyone before the beginning of Rousseauist modes of interior thought. (42.67)

A few entries later Frye writes that Pepys’s ” genre, the diary, is not a branch of autobiography, as Evelyn’s is. . . . When I try to visualize Pepys I visualize clothes & a cultured life-force. I have a much clearer vision of the man who annoyed Hotspur or Juliet’s Nurse’s husband. . . . He does not observe character either: I can’t visualize his wife or my Lord. Even music he talks about as though it were simply a part of his retiring for physic” (42.69). Frye, on the other hand, engages in a great deal of character observation—the character of his colleagues, his students, his family, his wife, and, most of all, himself. His diaries provide a rich and extensive psychological portrait. He does not set out to write a confession, but by the time we have come to the end of the diaries, he has confessed more than he perhaps realized.

But the diaries are also a chronicle. We peer over Frye’s shoulder as he trudges to his office, teaches his classes, attends Canadian Forummeetings, reflects on movies, socializes with neighbours and other friends, discusses Blake with his student Peter Fisher, works on his various commissions, eyes attractive woman, records his dreams, plans his career, judges his colleagues and his university, registers his frank reactions to the hundreds of people who cross his path, travels to Chicago, Wisconsin, and Cambridge, plans his fiction projects, reflects on music, religion, and politics, shovels his sidewalk, suffers through committee meetings, describes his various physical and psychological ailments, practises the piano, visits bookstores, frequents Toronto restaurants, reflects on his reading, and records scores of additional activities, mundane and otherwise. As a chronicle, Frye’s diaries are like Virginia Woolf’s, putting the most inconsequential event, such as cutting the grass, alongside the most sober reflection, such as the nature of the contemporary church or the unspeakable uselessness of war. His speculations on a wide range of critical and social and religious issues are not unlike those in a typical notebook entry. His notebooks occasionally become quite personal and thus move in the direction of the diary. His diaries very often become quite impersonal and thus move in the direction of the notebook. The context of the speculative passages is sometimes a contemporary event, as when the Korean War triggers his prescient views on the path that Communism will take during the last half of the century. Most often, however, the contexts for Frye’s speculations are the courses he is teaching or his writing projects. (CW 8, xxiv)