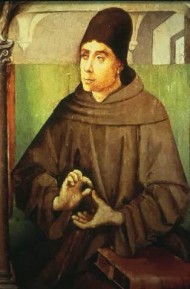

On this date in 1308, the scholastic theologian and philosopher Duns Scotus died.

In October 1936, Frye, newly ensconced at Merton College, Oxford, wrote Helen about the college legend that the ghost of Duns Scotus haunted his room:

Apparently the tradition I think I mentioned, that the ghost of Duns Scotus haunts this room and the one above it as well as the library (which is really an extension of my staircase) is quite well-known and of some standing. He has a long and cold way to come, as he’s buried in Cologne, but I can see where the legend of his haunting the library would originate: Merton had the best library in England during the Middle Ages and all of Scotus would be here, being the greatest English scholastic and a Merton man. Then the Reformation came, this library was plundered, the manuscripts torn to pieces and thrown into the quad, and of all authors the one singled out for especial destruction was Scotus. I asked my scout if he had ever sensed a ghost on this staircase, and he said no, but various people have put on surplices and awakened people by putting cold hands on them.