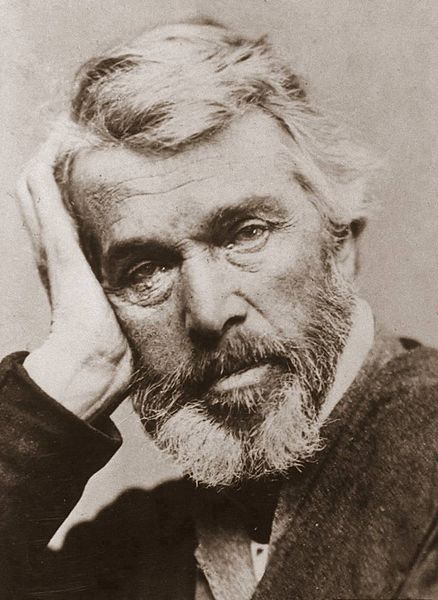

Thomas Carlyle died on this date in 1881 (born 1795).

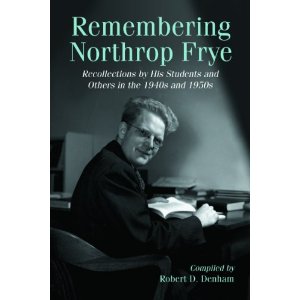

Frye in “New Directions from Old” cites Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus in order to make the point that literature does not present “ideas” by way of logic, but a mimesis of ideas by way of metaphor:

Literary criticism finds a good deal of difficulty in dealing with such works as Sartor Resartus takes the structure of German Romantic philosophy and extracts from it a central metaphor in which the phenomenal is to the noumenal world as clothing is to the naked body: something which conceals it, and yet, by enabling it to appear in public, paradoxically reveals it as well.

The “ideas” the poets use, therefore, are not actual propositions, but thought-forms or conceptual myths, usually dealing with images rather than abstractions, and hence normally unified by metaphor, or image phrasing, rather than by logic. (CW 21, 121-13)