“The present cannot really be known or understood except through the past. It follows inescapably that the more we know of the past the more we know of the present. As T.S. Eliot has . . . said, the poet is not likely to know what is to be done unless he lives in what is not merely the present, but the present moment of the past, unless he conscious, not of what is dead, but of what is already living.”

“I sometimes think with Oscar Wilde that lying, the telling of beautiful untrue things, is the proper aim of art.”

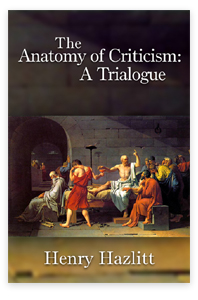

Do these two passages have a faint Frygian ring to them? They are from Anatomy of Criticism. Not Frye’s Anatomy but The Anatomy of Criticism by Henry Hazlitt, pp. 155 and 239.

While on the topic––In 1982 Wayne Booth wrote to Frye to apologize for listing Anatomy of Criticism as The Anatomy of Criticism in the bibliography of The Rhetoric of Fiction, saying that it would be corrected in the next edition. Frye replied: “Well, I don’t suppose it did any harm to either book to have mine listed as “The” Anatomy for a brief time. Most people when speaking to me about it say ‘your Anatomy,’ which is much more disconcerting. In the meantime, I am very pleased that ‘The’ Rhetoric of Fiction continues to do so well.”