While looking for a quotation in David Lodge’s 1990 book After Bakhtin, I rediscovered his review of Imre Salusinszky’s Criticism in Society, which is reprinted as the last essay in After Bakhtin. Criticism and Society is a collection of interviews with Northrop Frye, Jacques Derrida, and a group of influential critics at American universities, recorded by Salusinszky in the mid-1980s, at the moment when deconstruction was beginning to give way to schools of criticism more concerned with ideology and social identity. Some readers of this blog will know Imre Salusinszky’s work on Frye; he left academe some time ago to work for the newspaper The Australian and is now a well-known political and cultural commentator in Australia.

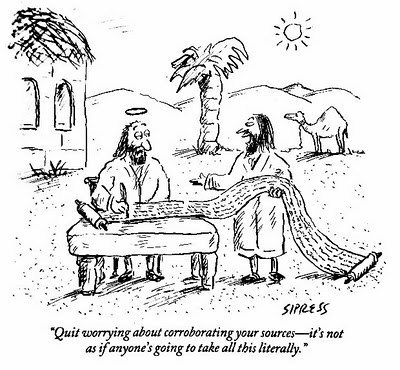

Criticism in Society came out the year that I defended my PhD, and I remember that it was read avidly by everyone with an interest in literary theory. I’m sure most readers were like myself in not fully taking in the prominent position that Frye was given in the book: we were mostly too interested in what the stars of Yale, Columbia, and Duke had to say. Lodge sums up Salusinszky’s premise in his own words as follows: “since literary criticism was virtually monopolized by the universities, it has become of all-absorbing interest to its practitioners and a matter of indifference or incomprehension to society at large.”

Lodge’s review is particularly resonant at the moment, as the humanities in the university seem to be returning to the same austerity conditions that prevailed during the 1980s. He observes that among the critics interviewed, “only Frye and Derrida . . . mention the problem of obtaining public funds for the humanities. If Mr Salusinszky had interviewed a batch of British academic critics at the same time he would have heard about little else.”

Lodge quotes Frank Lentricchia defending socially engaged criticism from an attack by Harold Bloom, then observes:

But there is a certain factitiousness about the counter-attack, betrayed by the familiar ‘Harold’. Nearly all the interviewers refer to each other, even when expressing strong disagreement, by first names – Harold, Geoffrey, Jacques, etc. (though not ‘Northrop’ – in this as in other respects, Frye is the odd man out. I wonder if anyone dares to call him Northrop). This style of naming again reminds one of the world of sport, where top athletes who compete fiercely against each other on the football field or tennis court share a kind of professional camaraderie at other times, a mutual respect based on their sense of belonging to a professional élite.

I wonder, however, whether criticism or theory has such an absorbing interest even for aspiring practitioners today? Are there nine critics today whose words in interview would be eagerly perused – and if not, is that a good or a bad thing? Has the pendulum swung back to interest in the creative writer? Perhaps we would rather read interviews with – to pick a few names randomly – Zadie Smith, Salman Rushdie, Nino Ricci, Martin Amis, or Lorrie Moore.