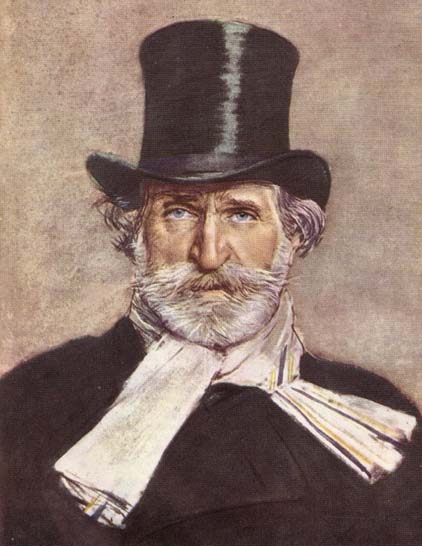

Further to Saturday Night at the Opera. We previously posted the finale of Verdi’s Falstaff here.

Scott was a source for the 19th c. opera—Donizetti’s Lucia & Bellini’s Puritani, the latter very loosely adapted from Old Mortality. I think not Verdi, though Verdi drew from a Romantic tradition that Scott did a lot to solidify: Hugo, Dumas, Schiller, etc. Nobody could imagine an opera of that period based on Jane Austen. If I try to rehabilitate Scott as a romancer, I should also try to rehabilitate melodrama. That term is usually used with contempt, & I’ve used it so myself, because of the way it approximates lynching-mob mentality in its hiss-the-villain setup. But there’s a legitimate type of melodrama where characters and plot outrage “probability,” yet seem to live in a logical world. I find Scott very hard to read now, but there are a lot of important critical principles extractable from him. (Late Notebooks, CW 5, 245–6)

Since the closing of the theatres in 1642, [Shakespearean comedy] has survived chiefly in opera. As long as we have Mozart or Verdi or Sullivan to listen to, we can tolerate identical twins and lost heirs and love potions and folk tales: we can even stand a fairy queen if she is under two hundred pounds. But the main tradition of Shakespearean fantasy seems to have drifted from the stage into lyric poetry, an oddly bookish fate for the warbler of native woodnotes. (“Shakespeare’s Comedy of Humours,” CW 10, 142). [This passage was incorporated into both “Comic Myth in Shakespeare” and A Natural Perspective.]

I did not, as I have indicated, see Fantasia, but I gather that the treatment of the Pastoral Symphony was a bit heavy handed compared to the delicate reference to it at the opening of the superb Farmyard Symphony, just before all the animals got to work on the Verdi Miserere. (“Music in the Movies,” CW 11, 110)

ALEXANDER: I’ve been most interested in some of the things you’ve had to say about music this evening. This last operatic excerpt, though, is of a very different sort. It’s the Finale to act 3 of Verdi’s Falstaff. Tell me why this is an appropriate way for us to end.

FRYE: Well, if I were asked who my favourite composer was, the answer would have to be Johann Sebastian Bach. So I suppose I have a particular affection for somebody who can display the acrobatic skill that Bach does in things like The Art of the Fugue. It’s partly for that reason that the greatest single moment in opera for me outside of Mozart is that Finale of Verdi’s Falstaff, the great fugue at the end. (CW 24, 742)

BOGDAN: You subscribed to Étude magazine as a teenager. Was that a Canadian publication?

FRYE: No, it was published in Philadelphia. The editors were all epigones of [Edward] Macdowell, who had been trained in Germany. So I picked up the notion that the only serious music was German music, and that Verdi and Puccini and so forth were just a bunch of organ-grinders. It took me a long time to get over that. (CW 24, 798)