The following is purely some associative riffing, but the eye-catching Sebastiane poster coincides with some of my reading of Frye at the moment. Struggling to nail down the quadrants of Eros and Adonis in his Great Doodle, Frye records the following entries in Notebook 6 of The “Third Book” Notebooks:

[11] The arrow is of course a central Eros image: in Dante’s Paradiso there is an arrow image in practically every canto. All ladders of love or perfection, Platonic or mystical, are erotic.

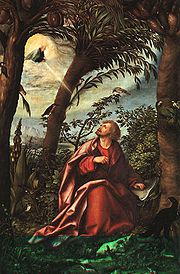

[13] (Kierkegaard was an Adonis figure, & I suppose the book called Stages on Life’s Way is the existential and tragic answer to Hegel, though it begins with some brilliant remarks about Eros & the comic). Incidentally, Kierkegaard speaks of the thorn in the flesh: Eros shoots arrows; figures stuck full of arrows, St. Sebastien & Actaeon, are Adonis figures.

[42] Everybody who knows, including Blake, agrees that Eros and Adonis are the same person, the continuous identity of an Orc-Luvah who is born as one and dies as the other. . . .

Frye then goes on to speak of the Protestant tendency to reject Eros (Milton and Kierkegaard) in contrast with the Catholic Dante who goes through Eros:

Both [Milton and Kierkegaard] focus on a rejection of Eros, Milton on divorce, oppposition to the C of L [Court of Love] code, and everything else inductive to the sin of Eve, Kierkegaard on the refusal to marry a woman who was in the ‘aesthetic’ sphere–Dido’s abandonment again. Under Eros I’ve got the St. Sebastian-Actaeon figure of Adonis stuck full of arrows & S.K.’s [Soren Kierkegaard’s] thorn in the flesh.

And in Notebook 12 [86]:

Birds: Eros shoots arrows & they hit himself as Adonis or St. Sebastien. The lecherous sparrow, the bird of Eros, kills the Adonis bird cock robin with the red breast, & the (female) nightingale pierces her breast with a thorn to sing. . . .

The plot of Sebastiane of course, as that of Beau Travail, appears to be very close to that of Melville’s Billy Budd, which features the same kind of Adonis or Orc-Luvah figure. The homosexual theme is central in all three works, along with the theme of sexual jealousy or envy (from what I can tell from the Wikipedia summaries: I haven’t seen either film, I am afraid, but am inspired to do so now).

Is this then the basis, archetypally speaking, of the apparently motiveless malignity of Judas’s treachery? Interestingly, Frye rejects the motive of thirty pieces of silver as not deep enough (it is part of the typological design at any rate), and implies that Judas is an Iago or Claggart type, or the other way around. Frye places Jesus not only in the Adonis quadrant–“the story of Jesus is given the Adonis or passion form” (114)– but in the homoerotic context of a man who leaves his mother and family to gather around himself, like Socrates, a group of loving young men. Both the homoeroticism and the Christ symbolism in Billy Budd is explicit: Billy is both an Adonis and a Jesus surrounded by loving male admirers and betrayed by one of them who “fain would have loved him except for fate and ban.”

Frye says in note 40 of Notebook 6 that “Eros moves away from the shadow” (the double of descent), “Adonis towards it,” and then observes in the next note:

Closely linked with this is the theme of friendship or male love: Plato’s pupil-teacher love is perhaps–in fact certainly–Eros, but the beautiful youth of Shakespeare’s sonnets, the theme in FQ [The Faerie Queene, bk. 4], the beloved disciple of Jesus, are all Adonis figures.