Peter, I think that your observation regarding the term ‘Mode’ is very interesting and may actually be quite important.

The title Anatomy of Criticism always struck me as being peculiar because it suggests that Frye was conscious of the fact that he was beginning the process of laying out the structure of literary theory. By using the word “anatomy,” its seems to me he was indicating that we were in the beginning stages of this type of analysis simply because in medicine the cataloguing of the parts of the body was a necessary step to understanding the processes of the body.

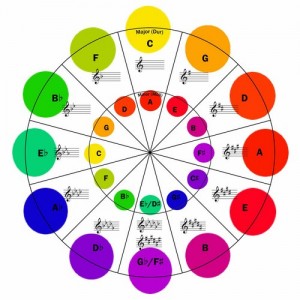

I agree with you that, when laying out his theory of literature and the circles of fifths, Frye must have made the association between the Quest Romance and the key of C for a reason. I have been thinking about the circle of fifths and literary theory since the first post on this blog, and the use of the word ‘Mode’ suggests to me that Frye had an even grander vision for how his anatomy crossed over to all forms of art.

That said, I balked a bit at the suggestion that Frye picked the key of C as an equivalent for the Quest Romance because it is the key which all keys can be translated into. I think we need to tread lightly when trying to decipher why he would do that. Frye, being a fan of classical music and a piano player, would have surely known his scales but to say that its the “key which all keys can be translated into” is a little misleading. We can transpose any piece of music freely between all keys; they are interchangeable. But I do think you are onto something, I simply wonder if it is more that the key of C has no sharps or flats, and that it is the most naturally organized key in our theory of music and on our keyboards. The idea that all other keys are expressed as functions of the key of C does not mean that the key itself or more specifically the sounds made in the key of C are any more important than those of any other key. The key of C is simply our home base, and it permeates our thinking about music as being the solid foundation which we build upon.

I wonder if that is closer to the connection that Frye was trying to make when assigning it to the Quest Romance genre. I think if we look at Frye’s explanation of that genre, we may find that the other genres that he talks about all use the Quest Romance as their frame of reference, just as all the musical keys refer back in our theories to the key of C. As for the modes of music, all the modes can be built in all keys — they apply to every scale. The modes simply change the starting and ending note of each scale within a given key. The Major scale in any key is called the Ionian Mode, and in the case of the C major scale it means you start on the note C and the scale follows Do-Re-Me etc. from there. Other modes simply start the scale on a different note. So the Dorian Mode begins on the note D in the C scale and proceeds up the scale with no sharps or flats until you reach D again as the eighth and final note. Modes are used to change the flavor of music within a given key but can be used in all keys. As an example, melodies written in the key of C but in the Dorian mode tend to have a Celtic feel. I have to think that Frye certainly would know this; so his use of the word ‘Mode’, to my way of thinking, must apply in the same way when dealing with literary genres.

This is a rich and interesting topic that needs more discussion.