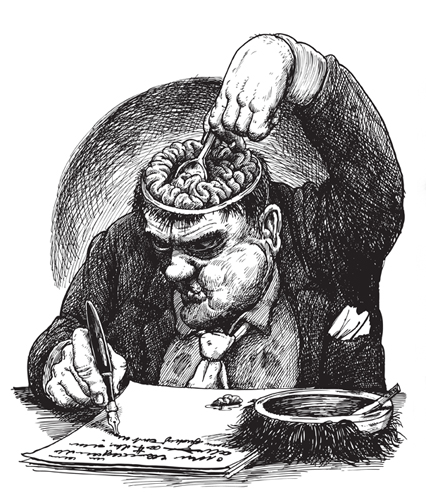

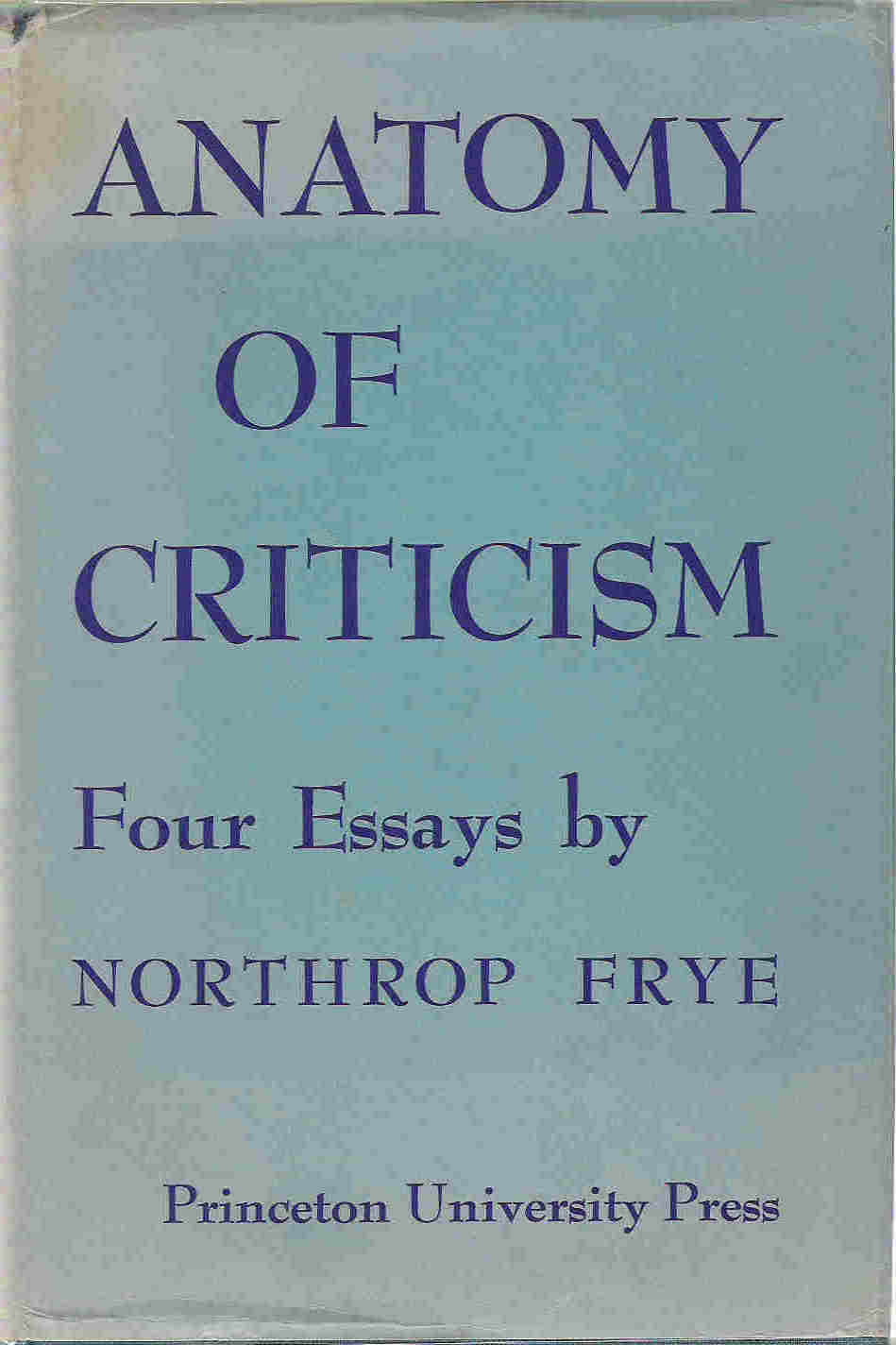

Robert Denham in his article, “‘Pity the Northrop Frye Scholar’? Anatomy of Criticism Fifty Years After”, begins with his own “relatively clear memory of [his] first encounter with Anatomy of Criticism” (15), and then moves on to give account of the various ways in which Frye was gradually displaced. Denham notes, for instance, Terry Eagleton’s (in)famous question, “Who now reads Frye?”, as well as Graham Good’s observation that “This is a wintry season for Frye’s work in the West” (17). I entered graduate school in 2004; Derrida died a month later. I was duly trained to think about literature critically, which is to say theoretically. My immediate reaction to Frye when I first encountered him was that literary archetype is both universal and essential, but I knew also these are notions that cannot be accepted: theory had told me so. Eventually, as is to be expected, I began to turn the tables on theory when it became apparent to me that I could apply theory to any book and somehow make it work – there was always a subtext of some sort that could be exploited for some theoretical purpose. Frustration ensued. How was I to study literature if it is just a game in theory application? One day a professor said to me: read this book and come back in a week. The book, of course, was Anatomy of Criticism. My copy of the Anatomy now sits in pieces, the spine broken, the margins marked up. (My edition includes Harold Bloom’s preface. The next book I read was The Anxiety of Influence.)

A few months after first reading the Anatomy, I delivered a paper on Frye at a graduate conference on Canadian Studies. During the “question” period which quickly became a “statement” period, I was summarily dismissed as a “Northrop Frye Apologist.” Indeed, my naivete was so profound that I did not realize there is such contempt for Frye in the academy, let alone that Frye requires an apology at a Canadian Studies conference. But, as Linda Hutcheon notes in her introduction to The Bush Garden, “Predictably (this is Canada), Frye’s particular conception came under fire – from the very start” (vii). Hutcheon is right about The Bush Garden, but her estimation seems to extend to most if not all of Frye’s writings. It was in that very moment I decided that Frye would be an area of study for me. Since then, I have purchased or been given every single volume of The Collected Works of Northrop Frye (except one) and have read through many of them, most particularly the introductions to each volume.

Finding Frye in 2006 was very different from finding Frye in the early 1960s, as was the case for Robert Denham. When I found Frye (or, as it now seems, Frye found me), the permanence of theory did not seem quite so permanent. Frye, in most instances, is now covered in survey courses of literary theory. I did not live through the denunciation of Frye or the distancing from Frye of the last quarter of the 20th century. But, then again, the salad days of high theory seem to be waning. The theory wars are in recession. Does this mean that studying Frye in the 21st century is without challenges? Not likely. The literary academic establishment is still fundamentally pre-occupied with theoretical concerns, and Frye is apparently not theoretical enough to be designated “Theory.” Likewise, writing, as I do, about Frye in the context of Comparative Literature (the House of High Theory) provides other challenges. Even so, studying Frye in such an environment is exciting precisely because reading him “fifty years after” provides its own idiosyncratic surprises, challenges and questions, not to mention persistent doubts. So is the goal of the Frye scholar today one of reclaiming Frye, apologizing for Frye, or simply finding him all over again?