Carmelo Tropiano is a Professor of English and Liberal Studies at Seneca College

“Literature [is]…a means of concentrating and intensifying the mind and of bringing it into a state of energy, which is the basis of all health.”

—Northrop Frye, “Literature as Therapy”

In November of 1989, Northrop Frye gave a lecture titled, “Literature as Therapy.” In his discussion, he expounds on the notion that literature possesses curative properties: That reading a novel or a poem, for example, in some sense restores both psychological and bodily “balance,” and that there is an inextricable linkage between the body and the mind that lends authenticity to the concept that “such imaginative constructs as literature…would have a direct role to play in physical health” (469). Frye provides several literary anecdotes to buttress his thesis (Dickens and Shakespeare), and then relates the following personal account:

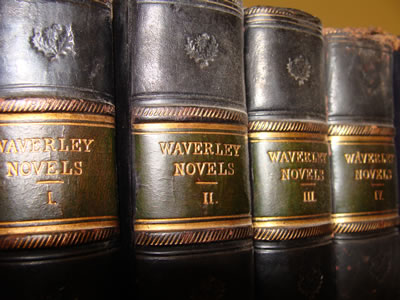

I remember my mother telling me of undergoing a very serious illness after the birth of my sister, and in the course of the illness she became delirious. Her father, who was a Methodist clergyman, came along with the twenty-five volumes of Scott’s Waverley novels and dropped them on her. By the time she had read her way through them she was all right again. (475)

The cathartic effects of reading appear to segue into the purging of destructive “imbalances” that contribute to physical illness. Perhaps part of the reason behind Frye’s mother’s recovery has to do with the time required to complete twenty-five volumes. What is, however, certain, and the main idea that Frye seems to suggest here, is that literature enables transformation; and that fictional texts, necessarily, do not have any creative boundaries imposed on them in the same way that non-fictional texts do. Rather than challenge the status-quo, non-fictional texts seem to reify what is. As Frye aptly notes, stories employ “poetic language,” requiring the reader to “detach himself” (474). What literature conveys “is the sense of controlled hallucination…where things are seen with a kind of intensity with which they are not seen in ordinary experience” (475). The literary experience foments ambiguity and dislocation—the aesthetic pedigree of the novel or short story is that they revel in the uncertain, the antithesis to the non-thought of received ideas that defy critical examination. How can we, for instance, query the biological construct of a cell or the number of nucleotides in a strand of DNA? Literature, on the other hand, approaches and expresses truths in an indirect sort of way, in non-explicit, non-objective trajectories. Reading means entering into the boundless possibilities of the imagined and is unsettling to the real-world with its plethora of codes, dense practicalities, and auras of conventionality. The story is the imaginative space where the inexorabilities and vicissitudes of existence are explored. It is little wonder why Plato banished the poets from his ideal republic (those involved in iconoclasm)—they offered a “counter environment” as Frye would say, “in which the follies and evils of the environment are partly reflected” and ultimately purged. The artist sets up something “antipathetic to the civilization in which it exists.” The artist’s vision is one in which the reader participates, and in such a way as to procure a deeper awareness of the world beyond one’s environment; it is a practice that enables a reader to gain insights, through appropriation, that will make his own life more comprehensible. For Frye’s mother, the “counter-delirium” offered to her by reading Scott’s novels facilitated what Coleridge called, “a willing suspension of disbelief”; that is, a susceptibility to being led into an experience that is potentially disruptive, and, in the end, transformative. The healing properties in literature, thus, are those that allow us to dislocate ourselves from our surroundings, and in Frye’s mother’s case, from herself and her illness. Our attention, therefore, will be on something else for a change, which surely contributes to “balance.”

Sources:

Frye, Northrop. “Literature as Therapy.” The Secular Scripture and Other Writings on Critical

Theory 1976-1991. Ed. Joseph Adamson and Jean Wilson. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006. 463-534.