Sigh. David Brooks and Tom Friedman.

I confess I cannot write extensively about either because I can no longer stand to read them. Brooks is a highfalutin reformulator of the conventional wisdom, a perennial apologist for the powers that be. (He’s supposed to be the thinking liberal’s conservative, but for my money the person who matches that description is Andrew Sullivan.) As for Friedman, it’s hard to imagine another serious columnist so undeserving to be taken seriously. He talks and talks and talks and talks. He says almost nothing worth hearing. He’s the Ross Douthat of “liberalism”, proving that, for the privileged, there’s apparently no greater privilege than watching the privileged enjoy their privileges.

But if I can’t rise to the occasion beyond ad hominem characterizations of professional hackery, I can at least leave it to someone who is very very good at it, and reads both closely enough to write extensive uproarious takedowns of their pretensions and considerable intellectual shortcomings — Matt Taibbi.

Taibbi holds Hunter S. Thompson‘s old position at Rolling Stone as chief political correspondent. Like Thompson, he’s as profane as he is articulate, and openly contemptuous of those who abuse their power. He’s also an old school journalist who does the legwork, gets the facts, and provides reportage that is not just cold-filtered polemic (take note, Maureen Dowd). Taibbi is the only high-profile, mass-circulation journalist to take on Goldman Sachs. Last year he produced a notorious article that had them running scared and included this often repeated formulation: “The world’s most powerful investment bank is a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.” Here’s a little taste from a post (“Let Them Eat Work“) that encapsulates Taibbi’s estimation of David Brooks:

Would I rather clean army latrines with my tongue, or would I rather do what Brooks does for a living, working as a professional groveler and flatterer who three times a week has to come up with new ways to elucidate for his rich readers how cosmically just their lifestyles are? If sucking up to upper-crust yabos was my actual job and I had to do it to keep the electricity on in my house, then yes, I might look at that as work.

But it strikes me that David Brooks actually enjoys his chosen profession. In fact, he strikes me as the kind of person who even in his spare time would pay a Leona Helmsley lookalike a thousand dollars to take a shit on his back. And here he is saying that the reason the poor and the middle classes are struggling is because they don’t work hard enough. Is this guy the best, or what? Does it get any better than this?

Now, that’s speaking truth to power. (More Taibbi on Brooks here and here.)

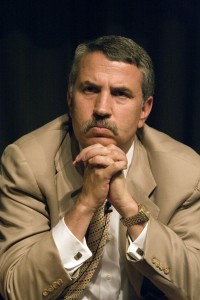

Meanwhile, Tom Friedman, liberal hawk after whom the “Friedman Unit” is named, writes, it seems, by association. He doesn’t manifest much evidence of thinking. He merely knots words together that sound to him like they ought to be entangled. He seems to be a bona fide example of an intellectual buffoon. Here’s Taibbi:

I’ve been unhealthily obsessed with Thomas Friedman for more than a decade now. For most of that time, I just thought he was funny. And admittedly, what I thought was funniest about him was the kind of stuff that only another writer would really care about—in particular his tortured use of the English language. Like George W. Bush with his Bushisms, Friedman came up with lines so hilarious you couldn’t make them up even if you were trying—and when you tried to actually picture the “illustrative” figures of speech he offered to explain himself, what you often ended up with was pure physical comedy of the Buster Keaton/Three Stooges school, with whole nations and peoples slipping and falling on the misplaced banana peels of his literary endeavors.

Remember Friedman’s take on Bush’s Iraq policy? “It’s OK to throw out your steering wheel,” he wrote, “as long as you remember you’re driving without one.” Picture that for a minute. Or how about Friedman’s analysis of America’s foreign policy outlook last May: “The first rule of holes is when you’re in one, stop digging. When you’re in three, bring a lot of shovels.”

First of all, how can any single person be in three holes at once? Secondly, what the fuck is he talking about? If you’re supposed to stop digging when you’re in one hole, why should you dig more in three? How does that even begin to make sense? It’s stuff like this that makes me wonder if the editors over at the New York Times editorial page spend their afternoons dropping acid or drinking rubbing alcohol. Sending a line like that into print is the journalism equivalent of a security guard at a nuke plant waving a pair of mullahs in explosive vests through the front gate. It should never, ever happen.

But it does happen. Week after week after month after year. And that’s exactly what’s wrong with the New York Times. (More Taibbi on Friedman here and here.)

The problem these days is not that there’s a lack of good commentary worthy of the name. The problem is that there’s a lack of it where it matters: on the networks, at CNN, in the New York Times, sources that remain the go-to destinations for millions of people for their news and opinion. Perhaps the networks and CNN can be written off at this point as infotainment whores driven primarily by ratings and revenue, and therefore more likely to run wall to wall coverage of the latest celebrity sex scandal than a single in-depth story on what is really happening in Iran. But the Times is not supposed to be part of the problem, and would never admit to as much. Given the influence and the reputation it enjoys, you’d think that when it comes to its op-ed columnists the Times can afford to demand the very best. But it doesn’t. And there’s no obvious reason to indicate why it doesn’t; although we might extrapolate an institutionalized disdain for a readership that is expected to put up with the frivolous, gossipy blather of Maureen Dowd twice a week. It’s worth pointing out again that the paper’s latest hire, Ross Douthat, was brought in to replace Bill Kristol — Bill Kristol — a war-mongering neo-conservative hack, an unapologetic early advocate for Sarah Palin, and a Fox News shill who enjoys a well-deserved reputation for being wrong about everything. His presence in the editorial pages of the paper of record for a full year was an ongoing insult. Why? Why, with all the talent available to it, does the Times foist upon us the intellectually inert and the ideologically deranged? Over just the past couple of years, could it really do no better than Bill Kristol and Ross Douthat?

The Times isn’t the paper of record by legacy alone. It’s not a bragging right. It’s something that must be proven every day. And as long as the paper indulges loose talk instead of informed opinion, it becomes a record only of the continuing decline of mainstream news.

Thanks for the tip about Taibbi. Just read a couple of the articles you linked. There are so many good lines. I love the one about Palin at the Republican convention: “It was like watching Gidget address the Reichstag.”

And yes, Thomas Friedman has always been loathsome.

Check out Dowd’s column on Elena Kagan today. It is a horrorshow, even for her.

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/16/opinion/16dowd.html

God, yes, the Dowd piece is scurrilous. It oozes with malice and envy.

I am reading this post after the one on Von Hendy’s “The Construction of Myth.” One way to appreciate how much is at stake politically in Frye’s conception of myth as counter-historical, and literature as the same insofar as it resurrects primary concerns in the face of their ideological distortions, is to read what passes for the “news.” Matt Taibbi’s assessment of David Brook’s work as half propoganda and half prostitution, and Tom Friedman’s as buffoonishly incoherent–and thus Michael Happy’s assessment of the New York Times as failing its readers by publishing writing of this quality–calls indirect attention, I think, to how vital it is that what ultimately informs a community’s understanding of their “times” is not the commentary of individual egos on the events of the day but the imaginative essaying of the meaning of those events in works of art. The real news, Frye taught, is what we participate in making, and the fitness required to make something new when we read is an educated imagination. I wonder how much of what’s actually new any newspaper, including the New York Times, is fit to print?