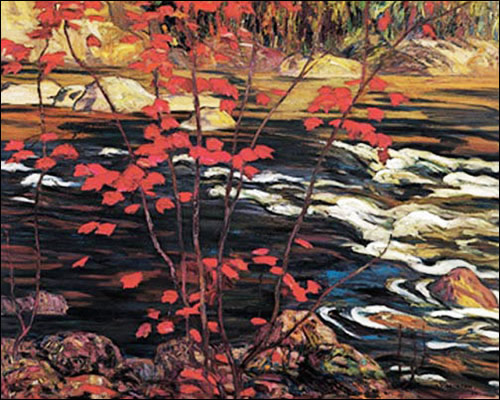

A. Y. Jackson, “Red Maple”

Jeff Mahoney of the Hamilton Spectator has an article today about a Westdale couple who’ve hunted down scores of locations featured in the paintings of the Group of Seven. This provides a nice opportunity to cite Frye on that remarkable group of painters.

From “Canadian Scene: Explorers and Observers”:

“[T]he primary rhythm of English Canadian painting has been a forward-thrusting rhythm, a drive which has its origin in Europe, and is therefore conservative and romantic in feeling, strongly attached to the British connection but ‘federal’ in it attitude to Canada, much possessed by the national motto, a mari usque ad mare. It starts with the documentary painters who, like Paul Kane, have provided such lively and varied glimpses of so many vanished aspects of the country, especially of Indian life. A second wave began with Tom Thomson, continued through the Group of Seven, and has a British Columbia counterpart in Emily Carr. (The romantic side of the movement is reflected in the name ‘Group of Seven’ itself: there were never really more than six, in fact there effectively only five, but seven is a sacred number, and the group had a strong theosophical bent.) One notices in these painting how the perspective is so frequently a twisting and scanning perspective, a canoeman’s eye peering around the corner to see what comes next. Thomson in particular uses the conventions of art nouveau to throw up in front of the canvas a fringe of foreground which is rather blurred, because the eye is meant to look past it. It is a perspective which reminds us how much Canada developed as a passage or gateway to somewhere else, being merely an obstruction in itself. Further, a new world is being discovered. There is an immense difference in felling between north and south Canada, but as north Canada is practically uninhabited, it exists in Canadian painting only through southern eyes. In those eyes it is a “solemn land” as frightening and fantastic as the moon. (CW 12, 422-3)

From “Lawren Harris”:

As a rule, when associations are formed by youthful artists, they break up as the styles of the artists composing them become more individual. But the Group of Seven, who did so much to revitalize Canadian painting in the ’20s and later of this century, still retain some of the characteristics of a group. Seven is a sacred number, and the identity of the seventh, like the light of the seventh star of the Pleiades, has fluctuated somewhat, attached to different painters at different times. But the permanent six, of whom four are still with us, have many qualities in common, both as painters and in fields outside painting. For one thing, they are, for painters, unusually articulate in words. J.E.H. MacDonald and Lawren Harris wrote poetry; Harris, as his book shows, wrote also a great deal of critical prose; A.Y. Jackson produced a most entertaining autobiography; Arthur Lismer, through his work as educator and lecturer, would still be one of the greatest names in the history of Canadian art even if he had never painted a canvas. For another, they shared certain intellectual interests. They felt themselves part of the movement towards the direct imaginative confrontation with the North American landscape which, for them, began in literature with Thoreau and Whitman. Out of this developed an interest for which the word theosophical would not be too misleading if understood, not in any sectarian sense, but as meaning a commitment to painting as a way of life, or, perhaps better, as a sacramental activity expressing a faith, and so analogous to the practicing of a religion. This is a Romantic view, following the tradition that begins in English poetry with Wordsworth. While the Group of Seven were most active, Romanticism was going out of fashion elsewhere. But the nineteen-sixties is once again a Romantic period, in fact almost oppressively so, so it seems a good time to see such an achievement as that of Lawren Harris in better perspective. (CW 12, 398-9)