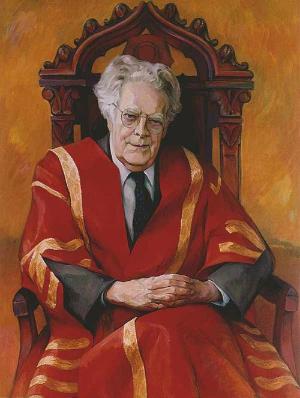

Frye in his robes as Chancellor of Victoria College

“Academic freedom is the only form of freedom, in the long run, of which humanity is capable, and it cannot be obtained unless the university itself is free.” (CW 7, 421)

I have recently posted on my concerns regarding a series of donations made to the University of Toronto by benefactors like Peter Munk, Leslie Dan, and Joseph Rotman. Even given all of the ways we might characterize their generosity, the issue that remains most important is the essence of the university. What precisely is the purpose of the university and what are its goals? What is the role of the university in society? In an age of global capitalism, it seems all the more important to ask such questions. It may be that I am nostalgic for a time I never knew, when the university was assumed to be the epicentre of thought, and whose value to the public good was never in question. Even so, I still want to ask the question: what is the university?

Northrop Frye writes that “a university is not, like a church, a political party, or a pressure group, primarily a concerned organization” (CW 7, 401). I wish all universities would work this principle into their Statements of Institutional Purpose. The university is not a political faction, not an ideological platform, not a pressure group, not a corporate enterprise. As Frye says, “the university itself stands for something different: it is not directly trying to create a certain kind of society. It is not conservative, not radical, not reactionary, nor is it a façade for any of those attitudes” (CW 7, 401). This is may be the kind of university setting some of us long for. Today, however, the university is increasingly caught up in the special interests of its private and corporate benefactors.

The issue is not simply a matter of questioning these interests for the sake of attacking them, but for the sake of preserving an institution whose role is unique:

As [its] authority is the same thing as freedom, the university is also the only place in society where freedom is defined. We may think of freedom, first of all, as something to be gained or increased by attacking the symbols of external compulsion in society. A good many of these, in every society, deserve to be attacked. But if we destroyed the external compulsions, we should still have the internal compulsions that made us attack them, and they would instantly produce a whole new set of external ones. (CW 7, 403)

Where does this lead us? Perhaps we must return to Frye’s singular vision of authority: “[t]he authority of the logical argument, the repeatable experiment, the compelling imagination, is the final authority in society, and it is an authority that demands no submission, no subordinating, no lessening of dignity” (CW 7, 403). And the notion of an authority like this one must be defended by the the most senior administrators at the university: the President, the Chancellor, the Principal, the Provost, the Deanery.

I have quoted this passage before, but it is probably worth repeating:

When anyone is considered for a deanship or a presidency, one of the first questions asked about him is, ‘How good a scholar is he?’ It sounds absurd to associate a man’s administrative ability with his specialized knowledge of a scholarly discipline, but the question is relevant none the less. If he has never been a scholar, he doesn’t know what a university is or what it stands for, and if he doesn’t know that, God help the university that gives him a responsible job. (CW 7, 314)

Finally, when it comes to the relation to the university to society, Frye observes in “The Definition of a University”:

The university belongs to its society, and the notion of autonomy of the university is an illusion. It is an illusion which it would be hard to maintain on the campus of the University of Toronto, situated as it is between the Parliament Buildings on one side and an educational Pentagon on the other, like Samson between the Pillars of a Philistine temple. But the university has a difficult and delicate job to do: it is responsible to society for what it does, very deeply responsible, yet its function is a critical function and it can fulfil that function only by asserting an authority that no other institution in society can command. It is not there to reflect society, but to reflect the real form of society, the reality that lies behind the mirage of social trends. It is not withdrawn or neutral on social issues: it defines our real social vision as that of a democracy devoted to the ideals of freedom and equality, which disappears when society is taken over by a conspiracy against these things. (CW 7, 421)

In this regard, the university is, as Frye would have it, the closest to a utopian space as we can manage, and it is therefore an ideal we must strive to realize today as much as we ever did in the past.

Frye’s vision of the university’s function in society gives me inspirational goosebumps. If only…if only it could be so. At the same, I’m invaded by an allusion to the royal court.

The closest stock character the university could play as member of the court is the Fool.

This is comforting.

I also recall that classic photo of Frye wearing a red clown nose. That image is comforting too.

Hi Bob. That picture of Frye in a red nose! I saw it back in the day, but it eludes me. Can’t find it. It was taken at a birthday party for Morley Callaghan which was attended by (among others) then-premier David Peterson and the great Alice Munro. It must have appeared in the Globe and Mail. I don’t suppose you have access to one?

In today’s Toronto Star (http://www.thestar.com/news/article/902572–u-of-t-slammed-over-jewish-racism-thesis?bn=1), the University of Toronto’s Provost speaks to the concern of academic freedom: “University of Toronto provost Cheryl Misak said ‘freedom of inquiry lies at the very heart of our institution’ and that ‘the best way for controversy to unfold is for members of our community to engage with the perspectives and arguments they dispute’.”