In the third essay of Anatomy of Criticism Frye isolates four story shapes–romance, tragedy, irony/satire, and comedy–which he understands as stages in a hypothetically complete narrative structure. Romance and irony concern movement within, respectively, an idealized world and a world of experience; tragedy and comedy concern the direction of that movement. Frye outlines and illustrates in detail these “narrative pregeneric elements of literature,” or “generic plots,” which are “narrative categories broader than, or logically prior to, the ordinary literary genres” (162). Frye’s work has been, even if noted, generally ignored by narratologists. And yet its elegance–its simplicity, comprehensiveness, and explanatory power–which allows it to account for such an extraordinary diversity of narrative literature remains unparalleled. As it is impossible to outline Frye’s very complex argument here, I will content myself with a brief illustration of the dynamic nature of his view of narrative structure.

For the sake of demonstration, I would like to look at his understanding of comic plot and in particular the assertion in Frye’s “The Argument of Comedy” that “tragedy is really implicit or uncompleted comedy” and that “comedy contains a potential tragedy within itself” (65). This statement is crucial to Frye’s understanding of narrative structure as based on conventions that derive their logic from ritual, an assumption shared, among others, by a formalist approach to narrative such Vladmir Propp’s.

One of the modern masters of comic structure is the director Frank Capra, one of the great creators of American film comedy of the thirties and forties. In many of his films he was fond of bringing “his action,” to use Frye’s description, “as close to a tragic overthrow of the hero as he can get it, and [reversing] this movement as suddenly as possible” (65). This feature is central to the “U-shaped plot” of comedy, “with the action sinking into deep and often potentially tragic complications, and then suddenly turning upward into a happy ending” (FI 25). This darkening downturn near the end of his films, often noted by critics as a mark of Capra’s particular style, a part of his signature, is in fact, if we follow Frye, a conventional feature of comic structure in general. Frye calls it the point of ritual death, and he gives a formulation of it in the discussion of comedy in Anatomy. He speaks of the action of comedy as

mov[ing] toward a deliverance from something which, if absurd, is by no means invariably harmless. . . . Any reader can think of many comedies in which the fear of death, sometimes a hideous death, hangs over the central character to the end, and is dispelled so quickly that one has almost the sense of awakening from nightmare. . . . An extraordinary number of comic stories, both in drama and fiction, seem to approach a potentially tragic crisis near the end, a feature that I may call the “point of ritual death”–a clumsy expression that I would gladly surrender for a better one. It is a feature not often noticed by critics, but when it is present it is as unmistakably present as a stretto in a fugue, which it somewhat resembles. (178-79)

The hero or heroine in comedy, then, is at a certain point threatened with death or a displaced version of it (false accusation and imprisonment) and then at the last minute escapes. In Mr Deeds Goes to Town, Meet John Doe (which is not always thought of as a comedy), Mr Smith goes to Washington, and It’s A Wonderful Life, the hero struggles against insurmountable odds to overthrow a usurping, “humorous” society which threatens to destroy him and the ideals he represents. In each case, he is isolated and falsely accused by his enemies, and threatened with disgrace, imprisonment, or death. The point of ritual death in comedy corresponds to the death of the hero in tragedy, the phase of pathos in the complete structure of quest-romance; in comedy pathos is invoked, but a tragic result is avoided, often only narrowly.

In the first three of the abovementioned films, often seen as forming a trilogy, it is worth noting how the suggestion of crucifixion attaches to the hero at this point. The word crucifixion is in fact explicitly used in all three to describe the fate that awaits the hero, as he is falsely accused, set up in a mock trial, and then only at the last moment delivered from the hands of his enemies. Mr Deeds is imprisoned, put on trial to decide his sanity, and is about to be defeated because he refuses to speak and defend himself at his own hearing; at the last minute, the situation is turned around by the woman he loves who inspires him to break silence, and the humorous society is at the last moment routed: the film ends with Mr Deeds being carried out of the courtroom in triumph by a cheering crowd and then the couple escaping behind closed doors. In the last frame Mr Deeds picks up his “bride” and kisses her, in a classic comic ending. As formulated by Frye: “The resolution of comedy comes, so to speak, from the audience’s side of the stage; in a tragedy it comes from some mysterious world on the opposite side. In the movie, where darkness permits a more erotically oriented audience, the plot usually moves toward an act which, like death in Greek tragedy, takes place offstage, and is symbolized by a closing embrace” (164).

Meet John Doe is a particularly good example, because it is often overlooked as a comedy and seen as an exception because of its particularly darkening mood near the end. But in structural terms, there is no difference; the dark mood is simply an intensification of the pathos which always makes its appearance at the same point in Capra’s films. The downward swing stems from a typical “comic” misunderstanding or confusion between the hero and the girl, one that we find in Mr Deeds, for example, or, in a lighter example of the same thing, in It Happened One Night, just before the comic resolution. In Meet John Doe, the hero again is falsely accused of imposture by his enemies. Feeling betrayed by the woman he loves, facing what looks like terrible defeat, he decides to do away with himself. He is perched on the ledge a great office building, about to jump. The lighting is very dark, it is midnight, when at the very last moment he is stopped by his girlfriend and persuaded by his friends to keep fighting. “Everyone will have noted in comic actions,” Frye observes, “even in very trivial movies and magazine stories, a point near the end at which the tone suddenly becomes serious, sentimental, or ominous of potential catastrophe” (179). Frye gives the example of Aldous Huxley’s Chrome Yellow, whose “hero Denis comes to a point of self-evaluation in which suicide nearly suggests itself : in most of Huxley’s later books some violent action, generally suicidal, occurs at the corresponding point” (179).

Capra uses the hero’s decision to commit suicide in the face of defeat to similar effect in It’s A Wonderful Life. The mood of the film, after Uncle Billy loses the bank deposit, suddenly plunges downward, and George Bailey finds himself swinging between rage, as he lashes out at those around him, and terrible despair. Turned away and threatened with calumny by Mr Potter–the heartless “humour” of the story (in his cold-hearted avariciousness clearly a descendent of the humours in Moliere and Dickens)– facing bankruptcy and the take over of the entire town by Potter’s grim utilitarian tyranny, he sees no way out and decides to end his life so his family may cash in on his insurance policy. He throws himself into the water, but is saved at the last minute by an attending affable angel, an architectus figure, to use Frye’s term, builder of the dramatic action, descendant of comedy’s vice figures, like Ariel or Puck , or the series of visiting Spirits in Dicken’s Christmags Carol. The bumbling angel is himself a humorous type, but of the congenial kind so favoured by Dickens as a counterpart to the villainous darker humours of his novels. Capra similarly abounds with congenial humours set against a humorous society of materialists and utilitarians.

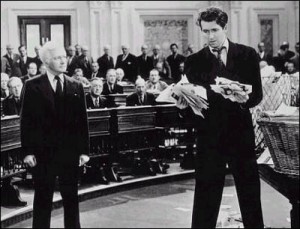

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington has precisely the same structure. The hero engages in a struggle to defend himself against a usurping society of crooks and hypocrites who are threatening to take over state politics; he filibusters, and fights back against false accusations of graft. He is pushed to the breaking-point, and seems to have been defeated by the conspiracy of his enemies who have trumped up false witnesses and evidence. As Frye observes, the movement of comedy is from pistis to gnosis, opinion to proof. Even as he vows to keep fighting, Mr Smith faints from exhaustion and falls to the ground. A crowd surrounds his motionless body, he is anxiously attended to, his pulse is taken, and we watch his girlfriend’s relief as she is given the signal that he is alright. In the very next moment, like the end of a Perry Mason episode, the crooked senator rushes in and confesses everything, cheers break out, and Mr. Smith is helped out of the chamber in triumph. Capra here pushes everything to the last possible moment of recovery. His films invariably end immediately after this point of reversal.

The often dramatic nature of this reversal in comedy depends, as we have seen, on the hero’s being pushed to the brink of tragic defeat, and therefore on a “device called catastasis or cleverly disguised recognition scene, where the recognitions are false clues,” in preparation of the final recognition scene, where “all is made clear.” Frye points out that “this device is also in Biblical imagery, where the catstasis is the convincing but ultimately false vision of the power of Babylon and Rome” (WP 265). It is, he adds, a device used in detective stories, “the plausible but false solution offered, usually by the police, just before the great detective arrives to straighten everything out” (265). In Capra’s films, this moment, often related to the point of ritual death, always looms large. In Mr Smith, for example, it is that moment when it looks as though the hero has been defeated and the power of the usurping humorous society has prevailed; or in Mr Deeds, when it appears he will keep his silence and the false accusation of insanity will stick; or in Meet John Doe, when the power of the fascist political coalition has been confirmed and proved itself invincible; or in It’s A Wonderful Life, when the nightmarish vision of Potter’s usurping society of heartlessness and greed seems invincible. In It Happened One Night, in a less ominous and threatening, but structurally identical way, it is the “convincing but ultimately false version” of the young heiresses’s impending marriage to the upper class jet-setter. In each of these cases, the presented outcome, which is an extremely likely but thoroughly undesirable conclusion, is then suddenly removed. The avoidance of what seems a likely, plausible outcome never strikes us as realistic, but it is very close to the heart of what makes comedy comedy. As Frye notes, in comedy, “The resolution . . . comes, so to speak, from the audience’s side of the stage. . . . Happy endings doe not impress us as true, but a s desirable, and they are brought about by manipulation” (164, 170).

In the context of this comic desire for a happy ending, we can see how the mock “crucifixions” of Capra’s heroes are consistent with Frye’s observation that “[t]he sense of tragedy as a prelude to comedy is hardly separable from anything explicitly Christian” (CW 28: 9). His point is the same as Capra’s when he speaks about the attempt by a writer, Arnold Schulman, to “end a comedy unhappily,” the irony being that Capra was in fact asking Schulman to change the tragic ending of a play he had already written and which had already appeared on Broadway:

Comedy may be many things to many people. But one thing it is not to anybody; it is not a tragic ending. . . . Comedy is fulfilment, accomplishment, overcoming. It is victory over odds, a triumph of good over evil. Tragedy is frustration, failure, despair. The evil in man prevails; there is mourning.

Comedy is good news. . . . The Gospels are comedies . . . The Resurrection is the happiest of all endings: man’s triumph over death. . . . It is a divine comedy.

One could say of Capra what Frye says of Dickens, that every film of Capra’s “is a comedy NB: such words as `comedy’ are not essence words but context words; hence this means: `for every novel of Dickens the obvious context is comedy'” (CW 17: 290). The obvious context for the pattern of dark mood and near defeat in Capra’s films are the viewer’s expectations of “a certain kind of structure and mood” that belongs to comedy.

In contrast with Frye’s “contextual” approach to narrative structure, structural and semiotic approaches have tended to ignore the conventional basis of meaning in literature and to turn to abstract linguistic models. This tendency has been acutely criticized by Paul Ricoeur, in “Anatomy of Criticism or the Order of Paradigms,” where he throws into question

this attempt by structuralist and semiotic narratology to reconstruct, to simulate at a higher level of rationality ,what is already understood on a lower level of narrative understanding. . . . What is philosophically disputable is the claim to substitute this form of rationality for the narrative understanding that precedes it, not just as a face in the history of culture, but also as a rule in the epistemological order of derivation. Such a substitution depends upon forgetting how rooted semiotic rationality is in narrative understanding, for which it attempts to provide an equivalent or a simulacrum on its own level. (1)

This imposing of a “higher level of rationality” is one way in which ithe ndiscriminate importing of “French theory” has harmed literary studies in North America. Ricoeur here puts his finger on the distinct advantage of Frye’s conception of narrative structure: its rootedness in what he calls this “lower level of narrative understanding,” where, from beginning to end, it follows the principle that fictional works are the expression or actualization (by readers or viewers) of narrative conventions. If we do not begin with this recognition, and go from there, we will find ourselves building castles in the air; however logical and rational, their purely deductive and abstract nature will make them irrelevant.