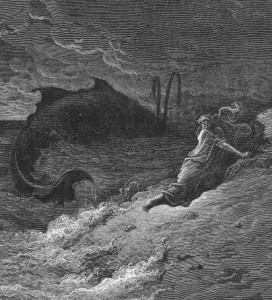

“Jonah Spewed Forth from the Whale,” Gustav Doré

“Tell me, who gives a good goddamn?

You’ll never get out alive!

Don’t go dreaming, don’t go scheming

A man must test his mettle

In a crooked ol’ world

Starving in the belly, starving in the belly

Starving in the belly of a whale!”

— Tom Waits, “Starving in the Belly of a Whale”

The following comments are in response to the previous posts on Frye and Melville, here and here:

Frye lived in Moncton, New Brunswick from about 1919 (there is a bit of uncertainty as to when the family settled here permanently) until 1929, when he left for Toronto and his life-long attachment to Victoria College. John Ayre, in his 1989 biography, states that “Frye once confessed that it [the Petitcodiac river that runs through Moncton] had given him the visual sense of Leviathan.” The Petitcodiac is a tidal river at the upper reaches of the Bay of Fundy. The Bay of Fundy has the highest tides in the world, registering 40 to 45 feet difference between low and high tide. The Petitcodiac fills and empties out twice a day and when empty it becomes, in Ayre’s words, “a monstrous deep trough of glistening mud which looks like an intestine split open.” The beauty of it, as people who live here discover, is in the way it continually recreates itself and becomes new again. Perhaps Frye too, looking into the monstrous depths of it, saw, with a sort of double vision, the beneficial power and beauty of it in its double pulsing of sea flood.

My own first visual (or perhaps more accurately, aural) sense of Leviathan came with reading Pinocchio at a very early age, probably in some abridged version. Pinocchio has the knack of getting into one scrape after another, and barely escaping with his life. Toward the end of the book he’s transformed into a donkey and made to perform by a cruel circus master. When he injures himself the circus master sells him for what he’s worth, which is next to nothing. The new buyer throws him into the ocean to drown him, so that he can then at least harvest his skin. A school of fish comes along and eats away at Pinocchio until there’s nothing left but his bones, which are “hard as wood.” What’s left is the wooden puppet body of Pinocchio, his true self. So he swims off, still looking for the ‘Blue Fairy’ who will save him. But before he can reach her, the giant sea monster (called the Dogfish in my present translation) comes after him and swallows him. “Suddenly he was in darkness as black as ink.” He was “a prisoner inside the stomach of the dreadful giant Dogfish.”

But all is not lost. Inside the monster he makes friends with Tunny, who will later help him swim to safety. Most amazingly, he stumbles along until he sees a light in the distance. “An old man with a flowing white beard and long gray hair sat on a chair at one end [of a table] eating a meagre meal. Pinocchio was overwhelmed to realize the old man was his father, Geppetto,” who has been imprisoned in the monster for two years. With joy and renewed energy Pinocchio plots their escape. In the depths of despair hope is reborn. Pinocchio, like Pip in Moby-Dick, has been “carried down alive to wondrous depths, where strange shapes of the unwarped primal world glided to and fro … and the miser-merman, Wisdom, revealed his hoarded heaps.”

James Wood’s essay (collected in The Broken Estate), called “The All and the If: God and Metaphor in Melville,” is a fascinating examination of Melville’s “growing infatuation with metaphor, an obsession which bursts into the love affair of Moby-Dick.” Toward the end of the essay Wood has this to say, which warrants scrutiny if not assent:

Moby-Dick is the great dream of mastery over language. But it also represents a terrible struggle with language. For if the terror of the whale, the terror of God, is his inscrutability, then it is language that has made him so. It is Melville’s abundance of language that is constantly filling everything with meaning, and emptying it out, too. Language breaks up God, releases us from the one meaning of the predestinating God, but merely makes that God differently inscrutable by flooding it with thousands of different meanings. I think that language and metaphor were a great torture as well as a great joy to Melville. Melville saw – and Moby-Dick is the enactment of this vision – that language helps to explain God and to conceal God in equal measure, and that these two functions annul each other. Thus language does not help us explain or describe God. Quite the contrary, it registers simply our inability to describe God; it holds our torment. Yet language is all there is, and thus Melville follows it as Ahab follows the whale, to the very end.