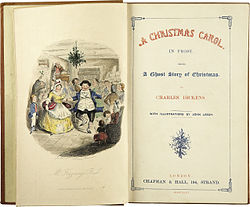

[First edition of Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol,” December 1843]

Frye on Christmas, from the Canadian Forum, 1947. Notice the question mark.

MERRY CHRISTMAS?

A passage in the Christmas Carol describes how Scrooge saw the air filled with fettered spirits, whose punishment it was to see the misery of others and to be unable to help. One hardly needs to be a ghost to be in their position, and as we light the fires for our Christmas they throw into the cold and darkness outside the wavering shadows of ourselves, unable to break the deadlock of the U.N., unable to stop the slaughter in China or India or the terror in Palestine, unable to release the victims of tyrannies still undestroyed, unable to deflect the hysterical panic urging us to war again, unable to do anything for the vast numbers who will starve and freeze this winter, and above all unable to break the spell of malignant fear that holds the world in its grip. Yet Dickens’ ghosts were punished for having denied Christmas, and we can offset our helplessness by affirming Christmas, by returning once more to the symbol of what human life should be, a society raised by kindliness into a community of continuous joy.

Because the winter solstice festival is not confined to Christianity, it represents something that Christians and non-Christians can affirm in common. Christmas reminds us, whether we put the symbol into religious terms or secular ones, that there is now in the world a power of life which is both the perfect form of human effort and all we know of God, and which it is our privilege to work with as it spreads from race to race, from nation to nation, from class to class, until there is no one shut out from the great invisible communion of the Christmas feast. Then the wish of a Merry Christmas, which we now extend to all our readers, will become, like the wish of a fairy tale, a worker of miracles.

(CW 4)