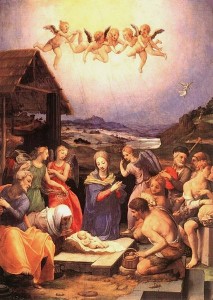

[Adoration of the Shepherds, Bronzino]

From the Canadian Forum, December 1949:

MERRY CHRISTMAS

The original Christmas was born of primitive fear. The fear of the growing darkness and the shortening days produced the rite of kindled fires, and the fear of winter the cult of the evergreen tree. Since then, Christmas has been wrapped up in one layer after another of an advancing civilization. Christianity came with its lovely serene story of a divine child and a virgin mother: the Middle Ages brought the carols, and then came the presents, the roast fowls, the mince pies, and the plum puddings. Our present form of Christmas, with its Santa Claus, its Christmas tree, and its exchange of cards, is a nineteenth-century invention, largely of German origin, the product of the age of Dickens and Albert the Good, of the British Empire and voluntary charities.

Yet even in this cosy urban middle-class Christmas something of the old panic recurs. There is unmistakable panic in the advertisers’ desperate appeals of “only so many shopping days left,” with its lurking threat that only if enough people spend enough money will this dollar civilization be able to stagger once more around the calendar. There is, if not panic, at any rate compulsion, in the popular response to this appeal, in the set faces of the women checking items off a list and in the apathy of their husbands trudging behind them, envying the bears.

What is the thoughtful observer to make of all this? Apart from the children, is it not the frivolous who enjoy Christmas, or pretend to enjoy it? Who else would find any real release in an orgy of synthetic gaiety as this dreadful century lurches to its halfway mark? Surely one is not a sour-faced Puritan if one feels, after listening to the radio reports of the cheering crowds in Times Square: “There is nothing here that reminds me of the birth of Christ; there is much that reminds me of Belshazzar of Babylon, who feasted while his city was in flames, and who could not read the writing on the wall” [Daniel 5].

One may find it instructive to compare the two Christmas stories in Matthew and in Luke. The Christmas story that we know and love is almost entirely from Luke. Matthew tells a terrible and gloomy tale of a jealous tyrant who filled the land with dead children and wailing mothers, while the wise men escaped from the country in one direction and the Holy Family in another. It is a tale in which all the characters except the tyrant and his minions are either murdered or refugees. Today we know as never before that this, too, is part of the Christmas story. But the story of Luke, with the shepherds and the manger and the angels singing hymns of peace and goodwill to men, does not cease to be true because the story of Matthew is also true. The story of Christmas, from its primitive beginnings to the present, is in part a story of how men, by cowering together in a common fear of menace, discovered a new fellowship, in fellowship a new hope, and in hope a new vision of society.

As Dickens shows us, the ghost of Christmas past brings us only regret for the past, and the ghost of Christmas future brings us only the terror of the future. But he also shows us that one of the surest ways of making the possible nightmare in the future come true is to fail to know and appreciate better the spirit of Christmas present. And so, without hypocrisy and as far as possible without frivolousness, we wish our readers once more a merry Christmas and a happy New Year.