As an addition to Ed Lemond’s informative post (here) on the often “intemperate”–as Bob Denham calls them–responses to Frye’s take on Canadian literature, here is an excerpt of my review of two recent collections on Frye, followed by a synopsis of Frye’s views, an excerpt from my own Northrop Frye: A Visionary Life:

First, an excerpt from a review of Northrop Frye: New Directions from Old, and: Northrop Frye’s Canadian Literary Criticism and Its Influence, University of Toronto Quarterly, vol. 80, No. 2, Spring 2011, pp. 322-324:

. . . Another disappointment is David Bentley’s essay on Frye’s contribution to the criticism of Canadian literature. The punning title “Jumping to Conclusions” is meant to be at Frye’s expense, but it applies much better to Bentley’s own argument. The essay consists almost entirely of passive-aggressive innuendo: the suggestion, for example, that Frye’s views were the outgrowth of neurotic anxieties about nature and animals, or that he was out of his league as a critic of Canadian literature and culture. How credible is the latter charge about a critic who for a decade annually surveyed the entire yearly output of Canadian poetry for this quarterly? Frye’s intricate knowledge of the Canadian scene–the whole scene: not just literature, but culture, politics, and history–is manifest to anyone who has made his way through the daunting volume of essays in Northrop Frye on Canada (vol. 12 of The Collected Works), which brings together his diverse writings on Canada. Most egregiously, Bentley’s essay never really confronts the argument of the epochal ‘Conclusion to a Literary History of Canada’; he simply hints at its contradictions and inaccuracies by quibbling over passages that he does not properly contextualize. Sadly, as Eleanor Cook observes in her essay in the other volume reviewed here, ‘for fifty people who can repeat the phrase “garrison mentality,” only one can repeat the critical argument in the”‘Introduction” to The Bush Garden and get it right.’ At the same time, Bentley conspicuously ignores Frye’s changing view of Canadian literature. Frye’s views altered as the quality of Canadian literature itself did with the emergence of writers like Margaret Atwood and Alice Munro. Frye, it seems, will never be forgiven for pointing out the limitations of Canadian literature before the seventies.

Any such patronizing treatment of Frye is happily missing from Branko Gorjup’s gathering of essays by different critics who have responded over the years to the influence of Frye’s Canadian criticism. The book opens with a sympathetic introduction by Gorjup and a fine epilogue by Russell Brown. The book serves as an illuminating documentation of Frye’s impact on Canadian writers and critics. It was the publication of The Bush Garden by Anansi Press under the editorship of Dennis Lee that brought Frye’s influence on Canadian literature to its peak in 1971. Frye’s presence as a cultural authority figure was always controversial, but by the end of the seventies, as the challenge of post-structuralism and ideological criticism waxed in strength, Frye quickly became a whipping-boy for the humanistic sins of his generation of scholars. Eleanor Cook has perhaps the most acute insights into the bad fortune of Frye’s legacy as a critic: she speaks of the ‘depressing’ reduction of Frye’s work to ‘slogans’ and notes the galling irony that ‘some of the departures from Frye’s criticism seem to me very close to the spirit of his work.’ It is perhaps even more true of his Canadian criticism than of Anatomy of Criticism that it is widely and peremptorily dismissed without any attention to the actual argument. And as with the vast body of writing that followed Anatomy, reconsiderations and developments of his earlier pronouncements in myriad essays and books, such as The Modern Century and Divisions on A Ground, remain largely unexplored. As Francis Sparshot points out, ‘In perceptiveness and in generosity of mind, The Modern Century excels many works in its genre that are far better known.’ Linda Hutcheon rightly observes that Frye’s sensitivity to the socio-cultural context of literature ‘comes out most clearly’ in his Canadian cultural criticism and that ‘those critics who have not looked at these writings frequently miss the important tension in his thought.’ This neglect is apparent even in as astute a scholar as Heather Murray who, in asking us to ‘read for contradiction’ in Frye, restricts her focus to the essays collected in The Bush Garden. The last word of this book review goes to David Staines, who concludes his essay by castigating those who ‘continue to find fault with [Frye’s] theories, not realizing that so much of their writing uses Frye’s enunciated myths as a point of departure.’ As he so nicely puts it, adapting an old epigram about Plato: ‘in whatever direction you happen to be going, you always meet Frye on his way back.’

The following, an excerpt from Northrop Frye: A Visionary Life (ECW Press, 1993):

Frye’s early view of Canadian literature was uncompromising and often unflattering. He saw it as the expression of an immature culture, there being “no Canadian writer of whom we can say what we can say of the world’s major writers, that their readers can grow up inside their work without ever being aware of a circumference” (Bush Garden 214). In retrospect, Frye’s opinion of his reviews of Canadian poetry was that

the estimates of value implied in them are expendable, as estimates of value always are. . . . For me, they were an essential piece of `field work’ to be carried on while I was working out a comprehensive critical theory. I was fascinated to see how the echoes and ripples of the great mythopoeic age kept moving through Canada, and taking a form there that they could not have taken elsewhere. (ix)

Indeed, Frye’s view of Canadian literature was to change dramatically by the end of his life, when he came to recognize that Canadian culture had at long last awakened “from its sleeping beauty isolation” (On Education 7). He would even go so far as to say that “This maturing of Canadian literature . . . is the greatest event of my life, so far as my own direct experience is concerned.”

It was, indeed, a direct experience, for he helped to bring that literature to adulthood. As a teacher, he came in contact with many of the young writers of a rapidly maturing literary culture. Frye, however, was never, as Margaret Atwood remembers,

“an `influence’ in the traditional sense. . . . He had no interest in producing a Frye school of writing, or any other form of cookie-cutter clone of himself” (Tribute 7). What he did do was to take the whole business seriously. He did not consider the arts a frill, but a central focus of a healthy society. . . . Lord help us, he even used to read Acta Victoriana, the Victoria College student literary magazine. If you published something in it, you were likely to get stopped outside Alumni Hall for a muttered but incisive comment or two, addressed to your shoes. (7)

As a critic, Frye’s particular sensitivity to formal and generic concerns “conferred freedom upon the artist to follow her or his own lights,” and part of that freedom came from his efforts

to help readers see what it was that they were reading. We all know the doggerel poem about critics: “Seeing an elephant, he exclaimed with a laugh, What a wondrous thing is this giraffe.” Perhaps one of his greatest gifts to writers was his lifelong work to ensure that if you created an elephant, it would never again be mistaken for a giraffe. (7)

It was this same concern with genre and literary convention, the insight that behind the individual work of literature stood a shaping “order of words,” which enabled him to provide the first comprehensive view of the Canadian literary tradition. As with so many of his other ideas, his views here were formed early and remained essentially unchanged: an essay on “Canadian and Colonial Painting” appeared in The Canadian Forum in 1940, and already contains his central insight into Canadian art as a response to the natural environment. Carl Klinck approached Frye to help edit what was to become Literary History of Canada (1965), and his conclusion to the volume represents his most complete formulation of Canadian literary and cultural history. The piece, in four parts, begins by outlining the historical, social, political, and economic factors which have helped to shape the “Canadian sensibility,” a sensibility “profoundly disturbed, not so much by our famous problems of identity, important as that is, as by a series of paradoxes in what confronts that identity. It is less perplexed by the question `Who am I?’ than by some such riddle as `Where is here?'” (220)

Frye observes that the early literature of Canada’s European inhabitants is marked by a “garrison mentality,” a protective and hostile attitude reflecting a “deep terror in regard to nature” (225). He further relates this sense of solitude–the experience of the isolated individual or parochial community of being surrounded by a menacing environment–as linked to the important tradition in Canada of the “arguing intellect” (227) of partisan, rhetorical and ideological argument. The latter is opposed to the “disinterested structure of words” (228) that we find in poetry or fiction, and its dominance is a sign that Canadian literature does not yet constitute a unique tradition but is in large part somewhat sub-literary. The Canadian writer has the difficult task of adapting the highly organized body of European verbal culture to what is essentially an alien natural environment. She or he must create a tradition of fiction and poetry in a cultural context not entirely conducive to it, one which, because of this sense of solitary adversity, has tended to favour realism over romance. “The conflict involved is between the poetic impulse to construct and the rhetorical impulse to assert, and the victory of the former is the sign of the maturing of the writer” (231). Frye’s point is that for a mature literary tradition to develop, imaginative writers must detach themselves from the natural and social world out there and find their “identity within the world of literature itself” (238).

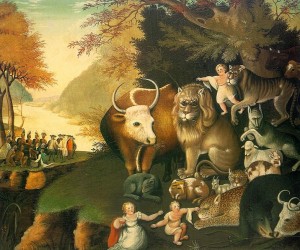

One obstacle to such a detachment was the deeply rooted perception in the Canadian literary tradition of the natural world as something unconscious, indifferent, and even hostile to human concerns. The problem is that such a vision of nature is finally a projection of the unconsciousness and the death-wish in human beings themselves. For Frye, the first poet to emerge from this tradition and show signs of a mature vision was E.J. Pratt, “with his infallible instinct for what is central in the Canadian experience” (226). In Pratt’s poetry, we are witness over and over again to the struggle of human dignity in the face of this death-wish in nature and man, perhaps most dramatically set forth in Brébeuf and his Brothers. When Canadian poets begin to find their identity in the world of literature, what they envision is a recreation of nature, a social and natural world transformed according to the models of the city and the garden projected by the poetic imagination. In the embryonic Canadian tradition, this depiction of the heroic struggle of the solitary individual or group against a terrifying natural environment contains the seeds of what Frye calls the pastoral myth, with its social ideal of “the reconciliation of man with man and of man with nature” (249). This ideal represents the return of the repressed vision of innocence associated with childhood, which tells us that the objective world is ultimately a lie and that the invisible world of the imagination is what is real; it is the “quest for the peaceable kingdom” (249) that Frye speaks of in the closing passages of that essay, and which he finds in Edward Hicks’ painting depicting the Messianic prophecy of Isaiah with its “haunting vision of a serenity that is both human and natural” (249).

[Edward Hicks, The Peaceable Kingdom]

Works Cited

Atwood, Margaret. Tribute. A Service in Memory of H. Northrop Frye. Convocation Hall, University of Toronto. 29 January 1991. Printed in Vic Report. 19.3 (1991): 7.

Frye, Northrop.—. The Bush Garden: Essays on the Canadian Imagination. Toronto: Anansi, 1971.

—. Divisions on a Ground: Essays on Canadian Culture. Ed. James Polk. Toronto, Anansi, 1982.

—. On Education. Markham, On: Fitzhenry, 1988.