Transcribed by Robert Denham

See also Bob’s blog post: Who Was Elizabeth Fraser?

(Click an image to view a larger version.)

Post Office Telegram, 4 December 1936

FRYE CARE BURNET 84 RICHMOND ROAD LONDON W2

THEN COMING SATURDAY ABOUT NOON = ELIZABETH

55A, High Street

Oxford. 31–12–36

Norrie, dear,

Life is unaccountable. Last night I wept on Mr. Long’s chest in the middle of Port Meadow, or, to be more exact, half-way along the tow-path, from Godslow.[1] Something was said about the Printer,[2] & I gave way all over, & Long was as surprised as you would be to find me human.

The Macdonald[3] is doing wonders on that man. He is now, for me, the perfect uncle,—provided a chest to be wept upon, & this led me firmly to The Golden Cross (via public lav is St. Giles)[4] where we drank three very dry sherries in quick succession. We then came home & I read him Thurber, & he (kind man) laughed.

Norrie, dear, I am going to send you my song, & though I see already that it is just my first flutter of fine words & fine sentiments, I want you to let me finish it, because of the last five plates, which, as I told you, occurred to me all at once. Besides, the whole thing is about something which I very definitely mean, but can’t yet make clear.

Ŏ’rangery, darling, (–ĭng–) n., is an o. plantation or house {Arab. naranj}.

Tom[5] called yesterday with a pot of damson cheese (1936) from his aunt. He also brought a box of wine biscuits with a card enclosed “to dear Betty & family,” which made us both roar. I told him about Edith’s[6] friend’s ink eraser, & he urged me to come to Aston next week when he will be back in town. He seemed about as anxious to see you there. So we shall explore Grim’s ditch without him. But I’m sorry, for the sake of a piano.

Mr. Long took me out to Eynsham to see his new finds in that chancel. They are pretty sketchy, but look like part of a fairly ambitious scheme, so he is very excited over the possibilities. We climbed about the benches with a feather duster imagining patterns beneath the plaster. We then walked along the tow path to Godslow with a suitcase & a walking stick & city shoes, where, within a stone’s throw you and I crawled around Wytham Wood on our bellies, six weeks or more ago.[7]

My song[8] is as old, except for the two words in the last verse, obviously post-Elliot [sic], and the galloping “dream,” perhaps also Elliot. Don’t laugh at it please.

I have a long and hair-raising letter from Esther Johnson.[9] If I thought it would amuse you I should send it along. But it wouldn’t. It would make you sick. It makes me sick too.

The family have now sent me cookies, a cable & a p. o., so I am returning your thirty bob. I may borrow it again at any time, so bank it carefully. Ask Edith for a cookie. They aren’t awfully good.—too ambitious. What we what is a plain oatmeal cookie. What Mr. Conkins wants is a real, deep, Cherry pie.

Write me sometimes,—not ambitiously. I don’t care what you write, or what I write, as you see. You are a swell kid. I like you.

Elizabeth

55 A. High Street

Oxford. 13–1–37

Darling Norrie,

The beautiful part about you is that you are not “young.” I have had a pipeful since reading your letter, & the more I puff, & the more I think you over, the more I glow,—with pleasure. I, Norrie, because I am beginning to get on in years, have more attacks of youthfulness than you, & this Printer, at sixty, is a mere child. But we are not young, any of us: we are not any age. Nobody is.

Darling Norrie, all along I have said to myself “this cannot be. The man is, in point of fact, twenty-four.” (This, if you will forgive me, is what I have said to Violette.[10] She is a wise woman, who takes pleasure in some people. You must write her now, from Edith’s, saying that you can’t get to see her, damn this pen, this visit.) But deep down, as you would say, I know that 24 means nothing. What confused me, if anything, was the word you used in October—”fiancee.” It is not your word.

Sweet Norrie (an absurd word, but you are sweet. For one thing you smell like a baby. And you have a beautiful face, and you know about your ears) I do not want to marry you. I do not want to marry anybody just now. At thirty-eight I may succumb to marriage. It will likely be a bad one.

But I do want to have a baby, for the most practical of reasons. The only trouble is that there are equally practical ones (or is it “-cable”) against having one. We shall weigh them when you come. I think the “no’s” should have it.

Yes, Long’s letter is good. Of course one discounts the gurgles. They are the Macdonald–Long language, & have nothing to do with me. That is the whole point of my sending you it. The man is switched right over onto another track, not entirely my doing. I only hope he will not run off these rails. There is a doubt that he has before.

Fleming, in his wife’s absence, was the Burnett idea of a solution to my Henry “crisis,” some years back. You will smile with me.

Woodsworth is supposed to be a good head. The trouble with the C.C.F. seems to be that there is only one of him.[11]

Why does anyone want to write a book about George Moore? Of all the ____ ____. (Quite honestly, I have never known how to fill in dashes.)

Darling, you are just a little young. Thank God.

Elizabeth.

Thanks for the p.o.s. Don’t be so damn shy about monies. Money doesn’t mean a thing, either, or anyway. Except that one must remember one’s debts, & I have a bad memory all round. With money I include gifts, & all things temporal. The Jews are awfully sane in this way.

Monday morning

Norrie,

Here is a substitute for 20. Destroy the other quickly. This, I feel, comes off, & it carried me through the initial & the title page. & with the t.p. I am pleased. I can now put away the three little bottles of ink, my four, with neat little labels, & get back to business.

And I want when you play. I want very very much to come when you play. Ask me to, Norrie.

Elizabeth.

55A. Monday

Damn your hide!

The chest was perfect, but unfortunately animate, so it presented itself again Friday, just when I was about to draw a picture. And I had to put down my pencils & have all about it, from four till eleven. I think the Burnetts’[12] closing time a good idea & am going to try to institute it here.

Actually it was quite funny. What happened to poor Long is that he looked the Macdonald up in town & met the gang, or the most obnoxious part of it (no, not the most obnoxious), & spent the evening trying to talk to it politely, instead of just lying down on bed with E. [Elizabeth Macdonald], which would, of course, have pleased everybody. The woman had a red gash across her face, the man kept stroking her neck. The man was rude to Long over the telephone, & rude in person. He told a feeble story about why he did not go to Christ Church, & they had an altercation over which of them had had the longest notice in the Times. They all, including, that is, Eliz. Macd. talked communism, & poor Long could only think how dirty Russians really are. Then to cap it all, E.M. spoke mysteriously of a collaboration—she seems to be doing a book with someone—& Long is seized with apprehension. Would he perhaps be lanky & damp-handed? he asked. (Do you know, Norrie dear, it is so long since I have used a question mark that I don’t know where ? to put it.)

Norrie, darling, how we seem to see alike. Only that I only see & you put it all down.

No, I have not met Rose Lamb.[13] Edith is afraid we will not like each other, as I told you.

Esther’s [Esther Johnson’s] letter I would now send you, but it is in scaps, & though I have fumbled about among the apple cores & doggers I can’t find any scraps worth enclosing. But you know Esther, & people are like themselves.[14] That is the only wonder. The letter was full of anglings & suggestive dashes, a sly & random reference to you, a great deal of sob-stuff about the downs, talk of a nunnery, a paragraph on sea-sickness (though they were neither of them sick) and an explosion of frustrated curiosity over the question of how I got back to England. That, at any rate, is the gist of it.

I enclose my last effort in the way of a letter. That was Saturday. Yesterday I did a good four hours work & feel better. So long does it take me to get back in gear.

I am not afraid that you will be sentimental. It is that, O God! Norrie perhaps I am. For my little pome [sic] contains everything but the carefully eschewed word love. It is perhaps symptomatic that I see the world in it. Some of the plates you will like, & as I can’t keep myself from them I may be sending an S.O.S Friday for 32/6.

Elizabeth.

Monday a.m.

Norrie dear,

This is awful. This letter is awful, the plates are awful. Even the drawing itself, as I see by what daylight there is, is awful. That comes of working by dark.

Zuckerman wants me to draw everything at once & come & watch him do dissections.[15] So my humour will grow daily worse. I have tried to go hatless with an umbrella (in section) but it doesn’t work.

Nothing for it but to resume this helmet,

E.C.F.

Monday, tea-time

Norrie, dear,

Perhaps I’d better have the p.o.’s back. I may be borrowing more off you later, simply because this month seems badly organized, but there would be no immediate need if it were not that Mrs. B[atchelor][16] is down with the flu, & there are little things I should like to get without asking for cash.

I myself have just enough of a headache to make letter-writing laborious. I am not getting the flu,—it is just that the strain is telling upon my disused house-keeping faculties. Not only is Mrs. B. in bed, but Mrs. Norman (char) is also down, & away, with it (flu). Yesterday I realized that a Batchelor day includes (amongst other things) the preparation of 24 trays of food. Strip life of almost everything, & you are still a parasite.

I enclose a letter from Long, to continue that story. (The Macd. [Elizabeth Macdonald] got flu, so I visited the sick Sat. morning & sent a report. This is the reply.) It is too late for me to do anything about Long’s handwriting, but think what I may in time achieve (indirectly) with regard to the Macd’s hair.

My pipe is snuffling, damn it. Needs cleaning.

Don’t toy with such mad ideas. Until we prove that we can tackle some small job together, we had better not undertake such a major one. If you don’t agree it only proves that I am too old for you.

Let’s try for recreation to make money this term. Finegold is a man of sense. He spent yesterday trying to stimulate me to such an effort. “Being a Jew,” he said, “I hate to see you not making money.” We agreed that there is not a poster abroad in town just now which is worth looking at. And he has a friend who can put me onto the right agents & so forth. At the notion of theatre posters & programmes I visibly brightened so he rushed off for an Observer, & ticked off the theatre list, & I have promised to begin work with a set of designs for “Murder in the Cathedral.”[17]

As you can see, I am off on my own rack again, but if Finegold can, incidentally, turn it into cash, so much the better.

Darling, our jobs are the same. It is that that I saw with alarm the very first day you came to tea. There is always the danger that we will confirm this with living arrangements. Sometimes the two are best linked, sometimes not. I think that Helen might make you the more effective. At any rate you must see her. And this term we are living at Oxford, I in the Batchelor home, you at Merton. Darling, let us clasp hands & be good.

Elizabeth. (over)

Look here: I want you to call on Violette Lafleur,[18] who, as you can see from this note, is the simplest of souls, but very nice. Her reserve, as I told you, is proverbial, & might be a treat for you after such a dose of family life. At any rate, if she asks you to a meal it will be in itself delightful. I shall write her by this post.

You can’t take Edith [Burnett]. They are both such perfect ladies that I shall have to introduce them in person. I tried to do this when last I visited Violette, & shall again. Tell E. that I shall.

Phone the lady. She’s “Miss.”—definitely.

I had better have her note back, sometime, partly that I may remember the 3 pts. of interest, & partly because it is the most loquacious one I have received from Violette.

You might possibly run into Stephen Glanville[19] there. He is the little big man who exploded over “Esquire,” got taken with psychic affairs, & war, with his wife, really good to me when I lived in town.

27-1-37

The Madeleine

It’s like the Madeleine, you said. Yes, I said, And probed my childish store of white Parisian impressions. You saw? Clearly you saw not before you, for you smiled distantly while I walked my memory for the Madeleine, which, then, was beautiful, and I walked my memory for the beautiful Madeleine, but always came up against the Opera, the Bank (English post, joy) and American layer cakes, and the Opera agitated memories of Rigoletto, and dress, and hot cheeks,— the beautiful Madeleine. So it was beautiful, and where then? So long as you’re happy, you said, handing me the world (and the Madeleine in it), and I looked upon the world in my hand while in the greyness of Jericho. Oh, I’m happy I said, and stared at the likeness of the Madeleine.

Wednesday night

Darling,

Maisie is nice, and is having an Opening Friday at wh. Northmoor will occupy a stretch of cream-coloured wall in a beautiful room. I am seized with a desire to hang the plates of the Long in one solid block with the words concealed.[20] Would you & I & Johnson be alone in understanding it or would we fell as naked as I felt we should feel? Oxford would surely take it for just a decorative splash, or am I just wanting to make gestures. Darling it is the sight of all that lovely cream-coloured wall & a garden beyond that makes me want to cover it with purple & scarlet. What do you think? We could have such a lovely time to-morrow rigging it up, with Hughes. And we could stay away from the opening. Perhaps I might hang the rejected swam end-papers in another corner. Perhaps the Madonna. What do you think?

Elizabeth

Bring the S. around to-morrow morning early if you think that something could be selected from it.

Saturday morning

If you haven’t come to see me, do so now at once. If I am not at home I shall be swimming (very efficiently) down the Cher.

In town I landed at least 30 quid worth of work, & the thought of so much money just out of touch has sent me clean out of my head.

Mrs. B.’s [Batchelor’s] milk bill has sent her clean out of her head. The whole household is stark raving mad. I have converted all that it left of it into Kotex.

Elizabeth

55A. Friday night

Norrie, dear,

Miss West, my old landlady, has just had tea with me, & it all went off very well. I had forgotten that the Batchelor house is an entertainment in itself, & that any two housewives will instantly agree about things like using the oven at no. 7 for light pastry. The gilt slippers have been replaced by just as ill-fitting gloves, but with two apples in addition she went away happy, I think. I like Miss West. I smoked my pipe, & she didn’t lift a hair: she can stand anything. And stood it, perhaps, last February.

You are going to see the plates all right. If you like them you can have the lot. I keep forgetting that I cannot show them to the Printer who doesn’t wish to be reminded of the things that life does to one from time to time. Don’t worry. I eschew nothing but, when I can, words which have become limp with overuse. Besides why need one say love when one has a brush full of vermilion in the other hand? The word “love” has been abused, the word “God” less so. I can still say “God” without discomfort. Soul I can still say, because it has the right sound, & the right vagueness. My bunches of words please me, ’though they will make you wrinkle your nose. They are my words, every one of them. The plates, as a whole, please me, though I have used yellow indiscriminately, & it is too late to cut it out. It is one of those very vital mistakes which often escape you at first. It is wrong simply because I could have done the book without yellow. Yellow is therefore abused.

But here is Long to tell me about the collaboration, no doubt. So no more. If I ever finish (the book) I’ll wine, simply because I like wines, & you must rush down at once.

Elizabeth

Don’t get flu. I hear there is an epidemic.

55 A. Monday

Darling,

I quite forgot to tell you that Long called on you Saturday. This may astonish you as much as it did me. He was looking at something around the chapel, & afterwards looked you up, or rather, your room, or, more particularly, staircase, since that was all.

E.F.

And let me know, silly, if ever you do get the flu, & I shall send Mrs. Batchelor around with a basket over her arm, & over the basket a napkin, & under the napkin a dozen fresh eggs and a milk jelley [sic] & me, of course, sweetness!

Sunday night

Norrie, dear,

You were wanted to-day, badly, as you may have gathered from Mrs. Boyd’s message.[21]

Come to tea.

Elizabeth

Wed.

Darling,

Still sitting here I that that really I do want to meet Blunden.[22] For one thing, after my next two or three efforts we will not likely all be here, in the same sense.

But you must make it painless or you will be a rat with 2 mice. 2 mice at one time are no fun, even for the cat. One mouse is watching the cat; the cat is watching the mouse. The other mouse is watching the cat & the other mouse. The cat is being watched by both mice from before & behind whichever way it looks: a most uncomfortable situation. And more people would only provide mouse-holes.

Elizabeth

And again, we might be 3 mice. [?]

Later.

Norrie, darling,

My second last shilling is about to give out, so I have turned out the gas, & must quickly tell you about the collaboration. —No, damn it all, it is worth the rest of this shilling. Besides my pipe has now gone out too, & 1 match will light both & be a great saving.

The collaborator, my dear Norrie, is an exceptional young man, a lawyer & a critic, a poet of sturdy well-knit build & possessive air,—damn this pen: it is about to make gobs. E.M. [Elizabeth Macdonald] came down with flu at the pantomime & is now in bed, with grapes from Long. To-morrow I am to visit the sick. I shall eat the grapes. Norrie, darling, I must do better. Long must marry E.M. I have promised myself that I shall tell you his secret if, & when, he does. He himself has done worse. He has offered to raise the price of the Northmoor job[23] (already paid in advance). I begin to feel like a gangster.

O yes, & Finegold came in in the middle of all this with an armful of records which will make your skin creep, & a lovely suggestion for rolling them one by one into the fire—a large open hearth level with the floor, like the one in Kemp Hall.[24] It is rather like throwing a discus.

F. also had a nice story about meeting a tall well-dressed man in a white scarf at the corner of New Bond Street, and suddenly being asked, “Do you know a good fish & chip shop near here?” A minute or so later he realized that the man was tall and well-dressed, & he is still wondering what he would have slipped him had he hit upon the right reply. This was apparently one episode in a day of quite exceptional madness: or in other words it was Finegold’s night.

Long wrapped himself up in my steamer rug & went to sleep—sitting, my dear, & afterwards continued the story of the collaboration.

I must now go to bed. To-morrow morning I shall be eating grapes—discussing Karl Marx with insouciance. I don’t know what insouciance means but it sounds well there, with the eating of grapes. People in too long doses affect me this way. I get a little light, & I hate it.

Norrie, darling, please do not get flu. Mrs. Batchelor is going down with it to-night. We shall miss her greatly. I shall have to practice timing eggs.

Darling (how I hate that word, but there is no other) life is getting all cluttered up. I shall have to move. I hate it to be cluttered with little things. I would like to love you & have a baby & earn its bread & do books, & collaborate with you. Norrie darling, I would like to collaborate with you! What a night.

Elizabeth

53 A. High Street

Oxford. 5–1–37

(Wednesday)

Norrie, dear,

Sometimes you talk sense & sometimes you don’t. How can sentimentality be one thing with you & another with me. And don’t worry, I’ve made a swell slobber all over 8 sheets of Whatman paper at 1/8 a sheet, fool that I am. And you’ll see it all, complete. In fact I may give it you.—If I don’t give it to the Printer [John Johnson]. That, my dear Norrie, describes the book, which is the damnedest mixture.[25] It is as though the Printer provided the pain, & you the release, the shot & the trigger, the What & the What. And like all mixtures, I suspect it of being foul, & wish to hell you had seen the scraps long ago, because it’s not worth waiting to see.

But you’ve got to see the words in place. And I’ve got to have all my swans around me, to work. So at the end of the vac you can have a look at it, & then we can talk of something else.

I enclose two letters hanging about from yesterday, just to show how I vacillate from hour to hour & how drunk I get, & what nasty slippery little cads all artists are when questions of l.s.d. [last stage of delirium? lust, sin, and death?] arise, but who cares. Somebody ought to shake me by the collar this week, but it wouldn’t do any good.

Darling Norrie!—

By the by, do you know yet that my knowledge of anatomy is far more exact than yours? Last night it at long last occurred to me to look into my Cunningham,[26] & Holy Moses if you weren’t trying to bust into my bladder or body in general. There sure would have been an explosion, &, I might say, a yell. Seriously, ask Edith [Burnett] if you’re supposed to get into the uterus itself, because it doesn’t look any more possible than it feels, as long as I still, as pray heaven I do, belong to the nulliparae.[27] Nice term that: Means you have lost caste both ways.

Must do swans.[28] Finegold brought the gramophone after all after all, but I think it can only decently remain silent until paid for.

Elizabeth.

55A. High Street

Oxford. 18–3–37

Norrie dear,

Here’s a nice simple letter from Charles Saunders,[29] because I can’t assemble one of my own. My cough racks me to the knees; I left my scarf in the Bodley; Long’s literary style is worse than Tristram’s,[30] but not bad as articles go; in 1845 the eye which I saw at Beckley had also a nose, & were said to belong to Joseph; Sir Thomas De la More, with the egg-shaped head “long passed as the author of a chronicle of the reign of Edward II on the strength of a passage in the works of Geoffrey Baker,”[31] but this, Long says, is all my eye; the semi-colon was a favourite in the ’forties. “In Norman work the Centaur or Saggittary [Sagittary] is frequently met with. The hippopotamus appears to have been the animal which suggested the centaur, although the only resemblance to a horse seems to be in its voice.”[32] In other respects human then. And do Piero della Francesca’s angels always have wings?

You may be shivering under the Alps now,[33] & you won’t have bought a woolen shirt, & I can’t send one after you because Mrs. B. has fleeced me almost of mine. I must therefore approach the Metropolitan cautiously before nine & then turn out the gas.[34] Curtain.

Elizabeth.

25 Kingston Road

Oxford. 6–4–37[35]

Norrie, dear,

Don’t look for me at 55A. when you return. I am at Miss West’s, & after the 19th shall be at no. 8, Osney Lane. When does term begin anyhow?

Elizabeth

Sat. 27th [May 1937][36]

Norrie dear,

Your letter ends a hell of a week. I enclose this really cheerful note written last Monday. Things then got so rapidly worse that I hadn’t the heart even to post it.

The Press (London end) began to take its time over the six pounds, question my estimate, & generally present its case in the most decent way,—there is always a choice of several. The first leisurely letter from them put me into a panic, so I wrote Long & told him to call if possible Wed., then rushed down to the Ashmolean & demanded a Cyprian pot job which I knew was coming to me, & we had a painful discussion of the textile situation, painful because E. felt sick as hell & began to ooze tears. [here page 2 of the letter is missing]

Finegold has left,—moved to Gloucester, &, to my surprise, he confided to me that he is cured of lodgings. So it is not me. Finegold is going to live in a hotel at whatever cost. I am going to live in a field.

Zuckerman[37] is going to America to-morrow & is in a terrible state,—fires going day & night in his living room, little trays of coffee coming & going. Elizabeth coming and going in between with drawings.

I have drawn one small head for Professor Seligman,[38] six pounds five worth of textiles, have made a bold gesture in the direction of the Metropolitan,[39] & drawn up a detailed estimate for Mr. A.U.P. And I have plotted the picture for my next book. Tell me that this is a good five days work.

Darling, how is your cold? And has Joseph[40] enough woolens for two? You should have had my rug. How stupid of me. It is brown & harmless, sweetness, & would go around you an infinite number of time.

55 A. 23rd

Tuesday [enclosed with previous letter]

Darling,

I slept with my feet in my hands last night, they were so cold. We have had snow. I have gone on a bob’s worth of gas from Thursday, ’till now & I worked last night untill three. Darling you fill me with, no, darling, stiffen my guts, shall we say. And I have not smoked. And there is only one “l” on the end of until, is there. That gives me away. I slipped in the “me” to make it sound nice. I should write a poem now, but I’d rather write you.

Darling, Iffley is a lovely village. I want to live there. I shall go & explain to Mr. Woodward to-morrow. It’s awfully near the Cowley works, but that couldn’t be worse than the Bacon factory concealed by some highly respectable fronts on the Iffley Road.

If you survived the Alps Italy should be a better place for this cold germ, which is really a formidable one. You must write at once and tell me that you survived. I myself have done nicely,

on sheer determination and wool to hand. And I earned five bob from Zuckerman (cash down) this morning, so I now have fire, as well.

Another twenty minutes Long called & gave me hell for going without gas.

So I didn’t borrow from Long. And Mollie’s five pounds came the next morning, & Mr. B. [Batchelor] received 4.5.0 at four o’clock, & 1 week’s final notice. (The thing that got me at 2 o’clock that day, was that she said “and what about the money, because the banks close at 3,” thereby disclosing fact that she had some money after all. The poor get stuck in the needle’s eye, as often as the rich.)

And the B.’s all left at seven a.m. Friday. And 5.5.0 arrived from Humphrey Milford at 8 a.m. And I slept 12 hours last night in a beautifully still house. And this morning I cash the 5.5.0 * wire 5.0.0 back to Mollie, & go & see Woodward, & then come back home & work like hell over textiles.

Darling, I have been a lazy beggar for a long long time, & now am paying for it.

I am reading some nice books on modern sculptors by Stanley Cannon. He is a friend of the Printer & talks just like him, & I’m afraid I like nice men. I got out as well one by Wilenski who yells & yells in the rudest way.[41] He was awful. Can’t think how I ever stomached him. Was, probably, then loving all Jews.

Darling, your letter,—All this trouble with everybody was just that I hadn’t heard from you, & now everything is all right, & I shall write the [Godlies?] & say OK cut estimate in two. Norrie’s in Rome, alive. Wot the hell.

Elizabeth

8. Osney Lane

Oxford. 18–6–37

Dear Frye,

Here is 12–0–0. It is the extent of Mollie’s savings, & she is handing it to me, not to you, & I am giving it to you, not lending it to you. Is that clear?

I will not even say “it will be time enough when . . . .” because that time never comes soon enough. I do not want to count on you for money, any more than I want to count on your book pleasing either publisher or public. Your book pleases me, & you please me, & here is all the money I can get to you now & when I can get money you can have it. Is that clear?

And now I would like to idle this weekend away with you, but I am not going to, because this twelve-pound gesture makes me feel strong & able to do things. Therefore come and hang about Osney when your job is done, & we will fan my little Eliot flame into being. I want all your help & all the Printer’s & then I shall do a perfect job, & if it is in every way perfect everything else will follow.

My own little book will stand aside, not because I don’t like it, but because its time hasn’t quite come. For one thing its medium is a quick brush outline, & my brush outlines are not yet as slick as the Japanese.

Elizabeth.

8. Osney Lane

Oxford. 21–6–37

Dear Norrie,

I have left you a note at Merton & paid Blackwell’s, & shall presently call on Mr. Boyd.[42]

The surest way of bringing news from F. & F. [Faber and Faber] would be to strike north with a canoe & Helen, & let people go out after you with planes & broadcast messages. This, incidentally, might be the quick way to fame. So don’t make things difficult for me by hanging around the Gordon Bay post office.

And I am going to give you my sister Margaret’s address, because she, as you know, can be relied on to meet emergencies, & how am I to know that your life will not be as full of them as mine? Margaret Fraser, then, c/o Johnson, Grant, Dodds & Macdonald, Canada Permanent Bldg., Bay Street. (corner of Adelaide & street below that. I forget which. s.w.)

And buy some dark glasses for ship board & lie in the sun like a lizard & freckles all over.

(Do not mistake freckles for beard.) And bury your prunes in bran and steal all the oranges, & relax & spread out all over the deck like soft jelly.

Elizabeth.

8. Osney Lane

Oxford. 8–7–37

Dear Norrie,

Clearly this does not call for two cables, so suppose you cable me, if you think sudden action necessary. I have overnight toyed with the notion of approaching the Cambridge U.P. on your behalf, & have decided that it would be a mistake. You must write me a series of fresh & inspired letters to all the publishers,—I shall warn you of this by cable if I have the price, but am not likely to have the price before this reaches you.

Miss Thorneycroft[43] says there is no hurry, as everyone that counts is away in Aug., & this is therefore a bad time to submit anything, especially the C.U.P. They are, however likely, she thinks, or not likely to be shy of young authors. And F. & F. [Faber & Faber] she would have thought unlikely, if only because they have not published Blake books before now. (They haven’t, have they? Who has? You must have told me twenty times.)

I feel useless, not getting the ms. off again overnight, but the rest of the world takes things slowly. If I have a brain wave I shall cable it, but if no cable arrives you may know that the best can be done in a letter to you.

We have acquired a great deal of oatmeal paper (samples enclosed) & have lost 9/6 so far. I say this frivolously & can stand my own losses, as you know.

Miss Thorneycroft still hopes to go to Russia, for 6 mos., and is leaving this week-end for somewhere. I enjoyed tea but was not at ease. It was funny,—she seemed to become her natural self quite early in the game, but without putting me there. I was feeling kind of tired & blue about the temples, & felt as though I were peering at her all the time & laughing mirthlessly. Must have been a strain for her. Poor Miss Thorneycroft.

Have you seen the New Yorker growth of the London Soil called Night & Day?[44] It breeds sentences like that, & it amused the Burnetts to send me a copy.

Miss Fisher produced a Canadian cousin last week-end,—so much more Can. than any of my own cousins that I was charmed. Monica now approves of me because of the connection.

I think I will do up the Prophecies in a new kind of wrapper, & I will read the ms. carefully, to make sure that F. & F. have not inserted any rude remarks or drawn oughts & crosses in the margins.

I made my effort all right, but I don’t know to what purpose yet. It produced a whole book of which one plate remains, & out of that something is coming. Johnson follows the stages though not admittedly. He is as sensitive to my successes as a touch-me-not flower. He has a way of walking around a plate with the indifference of a cat, & of freezing in it when it is worth something. I have a feeling that he would freeze on parts of your ms, but parts only. If he froze on the whole he would do something. No man in England can do more. And no man in England will do less for the incomplete.

I don’t quite know why I have said that,—I would scrap this sheet, but think that unfair.

In other words, Johnson is the only useful person I know, and I would not use him ever for you. He expects more of us both. He expects everything.

Write me a good letter for the Cambridge University Press, if that is next on your list, & I will send it & the ms. off with return postage. And meanwhile good luck to both you & Helen.

Elizabeth. (over)

(copy)

8. Osney Lane

Oxford. 8–7–37

Messrs. Faber & Faber Ltd.

24. Russell Square

London, W.C.1.

Dear Sirs:

Thank you for returning Mr. Frye’s ms. “The Blake Prophecies.” I shall forward your letter to him.

Yours truly,

Elizabeth Fraser

[The letter to Frye just mentioned]

H.N. Frye, Esq.,

c/o Miss Fraser,

8, Osney Lane,

Oxford.

Dear Sir,

We thank you for giving us the opportunity of seeing your ms. THE BLAKE PROPHECIES which we have read with interest and considered carefully. We regret, however, that we cannot foresee a wide enough sale for it to justify our undertaking its publication. We are, therefore, returning the ms. to the above address according to your instructions.

Yours faithfully,

FABER & FABER, LTD.

R.E. Stoneman

8. Osney Lane

Oxford. 9–7–37

Dear Norrie,

My last letter was probably a poem, because I take things like rejections awfully seriously. Please don’t you. I have been reading the ms, & it is good. Here is some spoor.

Am teaing with Mrs. Boyd Sunday (speaking, I suppose, of rhinoceri). She has been in Edinburgh, & there has been a polite flutter of notes between us.

Elizabeth Fraser.

8. Osney Lane

Oxford. 12–7–37

Norrie dear,

Bless you. Bless you both. My love to you both. I should remember Helen if she crossed my path again as your pink hair did. You must learn to compose music together. It is going to be needed.

And may I say something harsh? From your books you must come to expunge every whit of H.N. Frye or the world will not know how to use them. H.N. Frye is just one small wavering ant in a god’s-eye-view. Rather like all the other ants. But made to look too much like himself the other ants will not recognize him. And you are addressing yourself to the ants, not to God.

And for the same reason I do not want you to use the word Methodist, for more of the ants are not Methodist than are, & again they will say “this ant is a Methodist ant,” and feel shy. Methodist is too small a word. Even Christian is too small a word, even now.

But you will disobey me as you disobeyed me on board, & did not spread out in the sun & dream, but read four books & sat inside & swilled beer, & got off & looked at 33 pictures by 14 painters. And you will always disobey me because there is no reason why you should obey. I have no authority. I am simply an ant, antennae spread, waving uncertainly, crumb-like & crumbling landward.

Of downland soon shall I be chalk-hewn its long line of skyline be my line of [limb?] [strewn?] with grasses blown while in the starlight stars tears to my cheeks to my lips dew.

But more immediately I must wash the breakfast dishes. Monica—did I tell you?—was adopted because she was the naughtiest child in the whole orphanage.

Elizabeth

8. Osney Lane

Oxford. 26–7–37

Dear Norrie,

It looks as if I shouldn’t have your letter to the Cambridge Press before the end of the month. Remember that August is a useless month everywhere. Though it may be as well that the thing will not come back from its next journey until you are here to manage it, & with the second instalment.

Thanks for the pound. I have, in spite of myself, eaten myself steadily through it, but shall return it presently, for there will be no postal expenses which I cannot, & gladly will not, meet.

I have had another great Eliot bonfire, & there remains now only plate 1, a chorus of great slightness, something in a manner quite fresh to me, but closer to my Aston drawings than to any that have happened since.

Monica is having a birthday, with a cake in her school colours & two little friends to tea. And I have given her the little orange purse which Mollie’s mother gave me at Christmas time, & in it a little ivory rabbit which I found amongst the “squirrels” & spat on & polished up with a handkerchief, and, for luck, a more precious sixpence. I had tea with Mrs. Boyd yesterday & the Sunday before & the Sunday before & next Sunday, & have talked my heart out. She is a sweet kind woman & I am sorry she will not be here next winter to look after you.

I have always loved the Printer, but this week it shows a little more than usual, & I want to wear it on my face forever.

Elizabeth.

8. Osney Lane

Oxford. 30–7–37

Norrie, dear,

After this tight little effort to the C.U.P. [for copy of letter to Cambridge University Press, see below] I don’t feel much in a vein for rejoicing., & my first note of excitement over your appointment,[45] has had the misfortune to be read over again, & has gone the way of all stale efforts. I might say, though, that my brain nearly split with joy, because a spell of security is precisely what you need. And I am relieved to hear that you and Helen are going to settle into marriage.[46] That is also what you need.

Your letter to the C.U.P. was a bit too interesting. By a better letter I did not mean a more forceful one. My own effort was probably bad in the other way, but it will save time to get it off now.

As you can see I have had a talk with Blunden over it, & am greatly reassured. Blunden thinks it is a good book, but he wishes it was more freely supplied with breaks, of the sort he described as “landing-stages.” He would like you every now & then to get off from your subject & sidle up to it. He wants in other words bits of relief. The pictures will supply this to some extent, & if the selection is right I myself feel that they will supply it all. A picture in the right place gives exactly that kind of break. In the wrong place it is just a nuisance. So buckle down to pictures. Make your selection, if you can, or as much of it as you can, & I shall dig up reproductions and mount them & scatter them through the text for the beguilement of the publisher’s readers. Blunden is firm on this point. He says that the last thing a publisher wants to do is to read a ms.

He says Cape next.[47] And meanwhile you are to write Caines (how do you spell the great man’s name?)[48] & tell him all your troubles. Tell him that the ms. is now with the Cambridge U.P. & that if they reject it he, Caines, simply must, must look over it & push it at Cape. Perhaps nothing quite so vehement. But be helpless, & you might also murmur a few small nothings about pictures. These are going to be a damned nuisance, but remember that I can always buy a hat & go to see even Caines if necessary. You’d be surprised: I do quite well.

Blunden himself has dug up an old book with a few of Blake’s engravings, some new to him, but unfortunately I was by then so addled with sherry that I couldn’t, in the face of my naturally bad memory, take in the facts at all. One was a lady in bed with a thing like this waving its pseudopodia over her.[49]

The other struck me as really useful, but I don’t know for where. It was a swell layout,—the whole page, something like this:

The idea of a weather glass affair, a little roof and two little pictures, one of a gent & one of a lady, & below another little medallion, picturing three recumbent hares. You know so-and-so’s hares, said Blunden, & Elizabeth opened her mouth & said “ung?”[50] I can see that I’m going to be really useful.

Beside Cape he spoke of Denis & (I think?) Constable, & was so definitely cold about the O.U.P. that I no longer feel guilty into not being able to bully Johnson into doing the thing he never does. He also said is there any series in which it might fit? and we both said in chorus no!

He hopes you will improve your handwriting before you tackle schools. He thinks it would be a pity if they were put off by the scrawl, & come to think of it, it is scrawly, in spite of it’s too-tightness. So you must learn to hand-write. Greek would have cured you of its Canadian high-school tendencies & given it other faults. O well, Doug. LePan got a first & he must write like a Canadian.

Write Blunden at once, silly. And what about your trunk? Can you manage to get it across yourself?

B. says parts III & IV must come along too, as quickly as possible, or in time for Cape.

Now have a good year & thank your lucky fortune that Victoria College is being so gallant—over cash. And don’t start flinging it about, sweet as the gesture is. I’ll keep—did I say?—your pound towards Blake expenses, but I can manage to fill my own stomach.

Good luck to you both.

Elizabeth.

(copy)

8. Osney Lane.

Oxford. 31–7.37

The Secretary,

The University Press,

Cambridge.

Dear Sir,

I am submitting under separate cover a ms. “The Blake Prophecies” by H.N. Frye. Mr. Edmund Blunden has suggested that I do so. Mr. Frye is away in Canada just now, and may remain there next winter lecturing at Victoria College, Toronto. But he will be returning to Oxford in the spring, and meanwhile I am instructed to look after his correspondence.

I am sending you now parts I and II of the book; parts III and IV about double the length of the present manuscript. The author has taken these away with him for a last revision, but if you wish to see them he will be able to let you have them early in September.

It is his intention to illustrate the book fully from Blake’s own painting and engravings, and he has now only to select these illustrations and insert footnote references.

I enclose postage for the return of the manuscript.

Yours truly,

Elizabeth Fraser

4 August 1937

University Press

Cambridge

Dear Miss Fraser,

Thank you for your letter of July 31. All I can say at the moment is that I shall be very glad to see that Mr. Frye’s MS. “The Blake Prophecies” is fully considered in due course. I do not, however, think that we shall be able to do anything until we receive the second part of the MS. in September. The vacation meeting of the Syndics of the press has just been held, and they will not meet again until the end of September.

Yours very truly,

J.C. Roberts

On 5 August 1937 Fraser sent Frye a copy of the following reply to J.C. Roberts, with a note at the end, “So step on it!”

Dear Mr. Roberts,

Thank you for your letter of August 4. Naturally that is all you can do with Mr. Frye’s MS. “The Blake Prophecies.” And I shall get the second part to you as quickly as possible.

Very truly yours,

Elizabeth Fraser.

8. Osney Lane

Oxford. 7–8–37

Dear Norrie,

Good. But see that your marriage doesn’t get in the way of finishing Blake by Sept. 1st. Not that the book has anything like the importance of your marriage, but that Blunden is this time backing you, & Roberts’ letter was a damn-civil beginning, as even you should know. Gad the English never wait, and never regret having gone on.

And it you don’t stop sending me neatly dove-tailed love messages I shall have a fit of apoplexy. This habit is kin to the one of bestowing kisses on the nape of my neck in the presence of another male. It is thoroughly despicable, and relates you unpleasantly to people like Pelham Edgar. If it were not for this, & your theory that people should lie when it doesn’t matter (as if it ever didn’t!) you would be quite a pleasant young man. And I am becoming a virago. I feel that it will take a cloud of attendant furies to keep you down to the Blake.

Charles Saunders is dead, mother says.

Elizabeth.

8. Osney Lane

Oxford. 11–10–37

Dear Norrie,

I’d like you, when you have time, to call on mother, because I seem to have alarmed her lately & think you might describe life at Oxford in a more reassuring way. I have told her that you might have news of me, & the chances are that you & Helen will be asked to a meal. If you are, by all means go. She lives at 11, Delavan Avenue, 2 streets north of Lonsdale, running west of Spadina. It takes ages to get there, so telephone. Telephone no. I forget, but it’s under Mrs. A.W. Be a good boy.

Elizabeth.

9–11–37

Dear Norrie,

Rather than cable I’ve posted the MS, just as it came in this morning, because I thought if you do want to go over it, it had much better get off before the Christmas post. Then you can have it for the vac, & post it back to Capes in the January hell. This seemed more sensible, though if the MS. arrives for Christmas, all unforewarned, it will be a blow indeed. Sorry I can’t look at it, but it seemed wiser not to break the seals, & anyway I can’t do any good by looking at it. Shall write at tea time, when I’ll be freer.

Elizabeth

I opened the letter, of course. Couldn’t resist.

8. Osney Lane

Oxford. 9–11–37

J.C. Roberts, Esq.,

Secretary to the University Press,

Cambridge.

Dear Mr. Roberts,

Thank you for returning Mr. Frye’s MS. “The Blake Prophecies.” I have forwarded it, and also your letter, to him in Canada.

Yours very truly,

Elizabeth Fraser.

Mon. night

Darling,

I seized your ten-bob in the half dark &, mistaking it for stamps, nearly tore it up into small squares!

E.

30–3–38

Dear Norrie,

Write me a letter. I’m sorry I introduced you & Helen to mother. It seems to have been a bad idea.

Elizabeth

APPENDIX

One of Fraser’s medical drawings. From Alice Carleton, “Crossed Ectopia of the Kidney and Its Possible Cause,” Journal of Anatomy 71, pt. 2 (January 1937): 292–8.

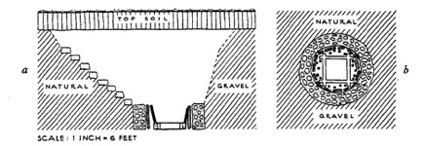

Fraser’s drawing of the Dorchester Puddling-Hole, reproduced from D.B. Harden’s “Two Romano-British Potters’-Fields near Oxford,” Oxoniensia 1 (1937): 90.

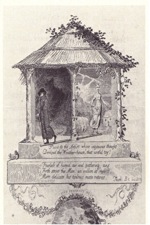

One of Fraser’s illustrations for Plato’s Academy.

Note initials “EF” in upper left-hand corner.

Notes

[1] E.T. Long is identified in Frye’s letters to Helen as a restorer of wall-paintings. In 1932 E. T. Long had restored paintings in the Northmoor Church associated with the Thomas de la More tombs, and he uncovered additional paintings in the recesses of the church. In his letter of 20 October 1936 Frye refers to Long as “a vaguely clerical person who lives out near Keble College and is apparently an expert on church architecture in general and stained glass in particular.” And in his letter to Helen of 30 November 1936, Frye says that Long is “a rather inconvenient friend of Elizabeth’s.” See E.T. Long, “Mural Paintings in Eynsham Church,” Oxoniensia 2 (1934): 204, and his survey, “Medieval Wall Paintings in Oxfordshire Churches,” Oxoniensia 37 (1972): 86–108; see also Long’s

“Medieval Domestic Architecture in Berkshire; Parts I and II,” Berkshire Archaeological Journal 44 (1940): 39–48, 101–13.

[2] John Johnson, the “Printer to the University” (Oxford University Press). In his letter to Helen of 9 February 1937 Frye writes that Elizabeth is “in love with one of the biggest men in Oxford—the printer at the O.U.P.” Earlier he had written that the printer “has been breaking her heart” (letter of 10 November 1936). Johnson was sixty years old. For Johnson’s extraordinary collection of printed ephemera, see http://www.bodley.ox.ac.uk/johnson/exhibition/coll.htm. Fraser helped to clean, mount, sort, and index Johnson’s collections for deposit in the Bodleian Library.

[3] Elizabeth Macdonald, a friend of Long’s.

[4] A wide street leading north from the centre of Oxford.

[5] This is apparently Frye’s friend Tom Allen, a student from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, studying at Merton College. Allen had a piano, and Frye and two other Merton students frequently congregated in Allen’s room to play Haydn, Brahms, Ravel, Mendelssohn, and Schumann.

[6] Edith Manning Burnett, who, with her husband Stephen, Helen Frye had come to know through Norah McCullough at the Art Gallery of Toronto. Helen had stayed at their home when she was in London studying art, and Frye stayed with the Burnetts on several occasions when he was in England. He had first been introduced to Elizabeth Fraser by Norah McCullough at the Art Gallery of Toronto.

[7] Frye had had a similar outing with Fraser the month before. They had headed northwest along the towing-path of the Oxford Canal to Wolvercot, and thence west along the Thames towing-path to Wytham, the northernmost village in Berkshire; from there they headed west again to Eynsham, which took them back into Oxfordshire. The distance between Oxford and Eynsham is about ten miles. “Saturday we went for what started out to be a walk around the country, but which ended up in a pub-crawl. We had morning coffee in Kemp Hall (nice name that place has) at eleven, and started up a tow-path north-west of here. It was a marvellous day, bright sun and dark rain-clouds on the opposite horizon, everything full of the subtlest lighting and colour-effects. This landscape almost paints itself, but then it does it so quickly—the sun goes behind a cloud for a minute and then you have an absolutely different picture. I t would break a painter’s heart, I should think—that is, a real painter: but I should think the temptation to sit down and dash off a bad water-color on the spot would be almost irresistible to a bad painter. I like this particular stage of the fall (autumn, these silly people call it), when the trees are almost emerging in black outlines, but still keep a few rows of russet tufts on them. We had lunch in a little village called Wytham (these villages and their inhabitants are exactly what one sees pictures of and reads about at home, which gives one rather a shock) and then discovered we were in a blind alley, as all the land around there is privately owned and they keep people out when they want to shoot pheasants. We started up a road and asked a long individual with two pointers snuffling along behind him how to get around his property—he was obviously connected with it—to somewhere else. He wore a green hat. He told us if we went through a farm “we wouldn’t do any harm”—rather a subtle remark, meaning essentially that we wouldn’t get shot in the pants by a pheasant-hunter, and the naivete of the Englishman’s worship of private property it embodied kept me laughing for the rest of the day. So we started toward the Thames, but instead of getting to the towpath ploughed along through a swamp, me getting my beautiful gray flannels soaked with muck and my shoes—I don’t know what the Boots [Frye’s Merton College “scout”] said the next morning, and probably couldn’t set it down if I did know. Elizabeth almost wept and said she ruined every day she planned, but I was really having a very good time. We had tea in an even more post-cardish village called Eynsham, and started up a highway, of all places, but it was getting dark and Elizabeth wanted to flag a bus and go home. We stopped one—a very swanky one for this country—and the conductor got out, glanced at our shoes, and said that this bus was much more expensive than another which would be along in ten minutes—one-and-six. We got in” (letter to Helen of 17 November 1936).

[8] The reference, apparently, is to a poem Fraser had enclosed.

[9] Johnson was a friend of Yvonne Williams, a Canadian stained-glass artist. Helen had written Frye that Johnson and Williams would be in London, staying at the Canada House, in October 1936.

[10] Violette Lafleur, the museum curator at University College, London. In 1939 she helped examine and restore the body of Jeremy Benthan, who had requested in his will more than one hundred years before that his body not be buried but embalmed and placed in a wooden cabinet. See Lafleur’s Interim Report on Jeremy Bentham, February 27th, 1939. Typescript, with covering letter from Professor Stephen R. K. Glanville, dated 22 June 1939, in Records Department, University College, London.

[11] The reference is to the Canadian socialist J.S. Woodsworth (1874–1942), founding leader of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation.

[12] The reference is to Edith and Stephen Burnett. See n. 6, above.

[13] Frye had gone to a party at Rose Lamb’s. See Helen’s letter to Frye of 20 January 1937.

[14] In his letter to Helen of 20 October 1936, Frye writes: “Esther [Johnson] and Yvonne [Williams] were in Oxford this week. They sent me a note, and we had tea at a place called Kemp Hall. Lovely name.”

[15] Fraser’s training was in medical and archeological drawings. The reference here appears to be some medical drawings she was doing for the man named Zuckerman, apparently Solly Zuckerman, anatomist for the Zoological Society of London.

[16] Mrs. Batchelor was proprietor of the boarding house at 55A High Street, London, where Fraser was living.

[17] Eliot’s “Murder in the Cathedral” played at the West End Theatre in London from November 1935 to March 1937.

[18] See n. 10, above.

[19] Professor of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology at University College London (1935–47) and, later, Professor of Egyptology, Cambridge University.

[20] This is an apparent reference to the tracings that Fraser has done of the wall-paintings from the Northmoor Church.

[21] Winifred Boyd, wife of Sir Donald James Boyd, entertained Commonwealth students studying in England.

[22] Edmund Blunder, Frye’s tutor at Merton College.

[23] That is, tracings of the wall-paintings in the church at Northmoor. In his letter to Helen of 11 December 1936 Frye writes that he and Elizabeth “went out to a little 14th century church in a place called Northmoor. I was to bring this pad along, but left it in Elizabeth’s digs in the morning. The point is that they had dug several pounds of plaster out of the north transept, revealing a tangled mass of red lines and flakes of gilt Elizabeth said were paintings.” Here is a photo of the indistinct remains of the painting in the north transept:

[24] Kemp Hall was a two-story stone and timber-framed building just to the northwest of Merton College, off High St., between St. Aldate’s and Alfred Streets.

[25] The book in question, one that Fraser is illustrating, is, Plato’s Academy: The Birth of the Idea of Its Rediscovery by Pan Aristophron, published in London by Oxford University Press in 1938. The edition, handsomely printed on handmade paper, contains thirteen full-page, two-colour illustrations by Elizabeth Fraser, plus an illustration for the endpapers. Only the first illustration is autographed with the stylized initials “E.F.”

[26] Daniel John Cunningham, Cunningham’s Manual of Practical Anatomy, rev. and ed., Arthur Robinson (New York: William Wood). The 9th ed. of this standard text had been published in 1935.

[27] Women who have never given birth to a child.

[28] The swan motif runs throughout the illustrations Fraser is drawing for Plato’s Academy.

[29] Letter from Charles E. Saunders dated 28 February 1937 was enclosed.

[30] E.W. Tristram of the Courtauld Institute in London was a scholar and restorer of wall-paintings. He would later publish English Medieval Wall Painting (London: Oxford University Press, 1944).

[31] Fraser is apparently quoting from one of Long’s articles. Sir Thomas de la More was from Northmoor; he was later a patron of Geoffrey le Baker. The wall-paintings at Northmoor are presumed to have been commissioned by de la More.

[32] Fraser is quoting—toward what end is uncertain—from J.L. Andre, “Notes on Symbolic Animals in English Art and Literature,” Archaeological Journal 48 (1891): 236.

[33] In mid-March Frye had headed down to London for a brief visit with Edith and Stephen Burnett before setting off on 18 March with his classmate Mike Joseph for a month’s tour of Italy.

[34] Fraser had proposed to sell the New York Metropolitan Museum tracings of the wall paintings in the Northmoor Church she had done.

[35] Addressed to Frye at Merton College but forwarded to him in Venice, Italy, c/o American Express.

[36] Dated by the postmark from Oxford.

[37] See n. 15, above.

[38] It seems likely that this is Charles Seligman, professor emeritus at the University of London.

[39] See n. 33, above.

[40] Mike Joseph. See n. 32, above.

[41] Doubtless The Meaning of Modern Sculpture (1932), which contains a vehement attack on the idealizing forms of Greek sculpture.

[42] See n. 20, above.

[43] Bursar and fellow at St. Hugh’s College, Oxford; friend of Helen Frye’s when she was studying art in London.

[44] A weekly magazine modeled on The New Yorker, which published fiction, poetry, cartoons, and political commentary, as well as film, book. and theater reviews.

[45] In July Frye was appointed a “special lecturer” at Victoria College for the following academic year.

[46] Frye and Helen Kemp had been married six days before the date of Fraser’s letter.

[47] That is, to send the manuscript to Jonathan Cape if it is rejected by Cambridge University Press.

[48] Fraser is referring to Sir Geoffrey Keynes, the great Blake bibliographer, collector, and scholar.

[49] The work by Blake described here is uncertain, but Fraser might have been referring to the frontispiece of The Gates of Paradise.

[50] Blunden had shown Fraser Blake’s etching of “The Peasant’s Nest and Cowper’s Tame Hares,” which Blake had executed for W. Hayley’s Life and Posthumous Writings of William Cowper.