Preface and Introduction to Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism

Robert D. Denham

[from Anatomy of Criticism. Ed. Robert D. Denham. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006. Collected Works of Northrop Frye, 22. Click an image to view a larger version.]

Editor’s Preface

The copy-texts of this edition of Anatomy of Criticism are the paperback editions published by Atheneum in 1965 and by Princeton University Press in 1971. Both editions, which are identical except for the covers and title-page rectos and versos, made two minor changes in the text of the first edition, published by Princeton in 1957: the correction of “as” to “at” and “critics” to “critic.” These changes appear in all of the reprintings to date—ten by Atheneum, fifteen by Princeton, and the reprintings by Penguin (1990). They appear as well in Princeton’s reissue of the book in 2000 with a preface by Harold Bloom.

No manuscripts for the Anatomy, which Frye himself typed, are extant. While there are holograph drafts of portions of the theory of modes in Frye’s Notebook 30d and the theory of symbols in Notebook 30e, we know very little about the process of revision the book went through before he sent it to Princeton. None of the changes to the manuscript that are mentioned in the subsequent correspondence with Benjamin F. Houston, the literary editor at Princeton, is substantive, so whatever revisions the book might have undergone appear to have been before Frye submitted the manuscript. Frye’s later practice was to make holograph changes to his own typescripts, which he then gave to his secretary Jane Widdicombe to type. The revised typescript would then itself be revised and retyped, often more than once. But as Frye did not have a secretary in the early 1950s, whatever revisions he made to his own typescripts, which he most certainly made, are unknown. On the other hand, we can infer a great deal about the process of composition before the typing stage from the sixteen notebooks that are devoted in whole or part to the Anatomy—some 130,000 words of holograph material that are the workshop from which he crafted his books. The composing process is an issue too large and complicated to address here, though certain of its features will be glanced at in the introduction. A full account cannot be made in any event until the publication of the Anatomy notebooks—an absorbing body of material that will appear in due course.

The text used in the present volume includes the original page numbers, italicized within square brackets. The pagination for all subsequent editions and reprintings remained unchanged. When a page break occurs in the middle of a word, the page number has been placed after the originally hyphenated word. When references to Frye’s books include two citations, the second, preceded by “CW and a volume number,” is to the page number in Collected Works edition of the text. References to Frye’s still unpublished notebooks are cited by notebook number, followed by a period and the paragraph number (as in 7.250).

The editorial principles of Frye’s Collected Works require regularized punctuation and spelling. Frye’s practice of hyphenating such prefixes as “non-” and “anti-” before words beginning with vowels have, for example, been modified, and many of his spellings have been changed from his general preference for American forms to British ones. Such tinkering may seem curious, but from an editorial point of view consistency is to be preferred in a Collected Works over the differences found in Frye’s own practice and in the diverse requirements of his publishers. Several spelling errors and nonsubstantive misquotations have been silently corrected, and the few places where the text has been emended are listed following the Notes.

Frye’s own notes, which have occasionally been expanded, are followed by “[NF].” The other notes are devoted mostly to providing the sources of Frye’s references or to explaining some point in the text. They occasionally expand Frye’s own citations. The line numbers of poems are generally given in square brackets within the text.

Anatomy of Criticism has been translated into fifteen languages. The title pages of fourteen of these (the Hebrew one has proved impossible to obtain), including two translations each in Chinese and Serbo-Croatian, are reproduced in the Appendix.

Introduction

In the commonplace manner of speaking, things well known need no introduction, and Anatomy of Criticism, being republished now in the year of its golden anniversary, is as well known as any critical text of the last century. Its arguments have been with us for a long time, and its ends and means have been repeatedly anatomized by countless readers, sympathizers as well as detractors. Its influence has been widespread in the Anglo-American critical world and beyond. In the English Institute volume devoted to Frye’s work less than a decade after its publication, Murray Krieger advanced the bold opinion that because of the Anatomy Frye “has had an influence—indeed an absolute hold—on a generation of developing literary critics greater and more exclusive than that of any one theorist in recent critical history. One thinks of other movements that have held sway, but these seem not to have developed so completely on a single critic—nay, on a single work—as has the criticism in the work of Frye and his Anatomy.”[1] This claim was echoed by Lawrence Lipking six years later: “More than any other modern critic, [Frye] stands at the center of critical activity.”[2] In 1976 Harold Bloom declared that Frye had “earned the reputation of being the leading theoretician of literary criticism among all those writing in English today,”[3] and a decade later Bloom had not changed his opinion: Frye, he wrote, “is the foremost living student of Western literature” and “surely the major literary critic in the English language.”[4]

Fearful Symmetry (1947), Frye’s pioneering study of William Blake, established his preeminence within the relatively limited confines of Blake scholarship, but Anatomy of Criticism was the book that launched his international reputation and, considering the widespread attention it still receives, continues to guarantee it. Frye’s writing career spanned some sixty years, beginning in the early 1930s and concluding with his two books on the Bible and The Double Vision (1991). Some thirty books followed in the wake of the Anatomy, and each book has an integral place in Frye’s grand achievement.[5] Interest in the Anatomy is said by many to have waned in the 1980s and 1990s, as Frye was displaced from his position near the centre, at least in graduate programs of literary study, where poststructural modes of inquiry came into fashion. And in the last two decades of his life, a large measure of the interest in Frye was directed more toward his literary interpretation of the Bible than his early theoretical work. The Anatomy, however, did not so much disappear as enter into the critical tradition. In his first edition of The Critical Tradition: Classic Texts and Contemporary Trends (1989), David Richter placed Frye’s “The Archetypes of Literature” in the section of his anthology devoted to “contemporary trends,” and the particular trend he was said to be a part of was, somewhat reductively, psychological criticism. In Richter’s view, Frye was a member of the camp that included Freud, Jung, and Lacan. But in the second edition of The Critical Tradition (1998), “The Archetypes,” along with the essays by Freud and Jung, had become a “classic text.” A classic text is one that has become a significant part of the critical tradition.

The reputations of critics, like those of poets and novelists, wax and wane, as we can see in the changing contents of the three editions of a widely used anthology of literary criticism more than a half-century ago, Smith and Parks’ The Great Critics. Where now are Antonio Sebastian Minturno (ca. 1500–74) and Henry Timrod (1829–67), both anthologized in the third edition of The Great Critics?[6] Although the major status of, say, Aristotle and Sidney seems assured, no one can predict with any certainty the extent to which those closer to us will remain in the critical canon. Critical fashions come and go. By the beginning of the present century, even Harold Bloom began to express some ambivalence about his earlier judgments, recorded above. In his foreword to the reissue of the Anatomy in 2000 Bloom remarks that he is “not so fond of the Anatomy now” as he was when he reviewed it forty-three years earlier.[7] Bloom’s ambivalence springs from his conviction that there is no place in Frye’s myth of concern for a theory of the anxiety of influence, Frye’s view of influence being a matter of “temperament and circumstances.”[8] Bloom’s foreword, however, is devoted chiefly, not to the Anatomy, but to his own anxieties about Frye’s influence, presented in the context of Bloom’s well-known disquiet about what he calls the School of Resentment—the various forms of “cultural criticism” that take their cues from identity politics. In the 1950s, Bloom says, Frye provided an alternative to the New Criticism, especially Eliot’s High Church variety, but today he is powerless to free us from the critical wilderness. Because Frye saw literature as a “benignly cooperative enterprise,” he is of little help with its agonistic traditions. His schematisms will fall away: what will remain is the rhapsodic quality of his criticism. In the extraordinary proliferation of texts today, according to Bloom, Frye will provide “little comfort and assistance”: if he is to afford any sustenance, it will be outside the universities. Still, Bloom believes that Frye’s criticism will survive not because of the system outlined in the Anatomy, but “because it is serious, spiritual, and comprehensive.”[9] We will return to Bloom’s characterization of the Anatomy as spiritual, as well as to his relation to Frye.

If Frye is no longer at “the center of critical activity,” he is certainly very much present at the circumference as a containing presence. While it is true that graduate courses in critical theory often exclude his work, it is no less true, as a glance at current university catalogues and course descriptions reveal, that both undergraduate and graduate students continue to read his works at a number of major universities.[10] And if Bloom’s claim is true that Frye will disappear from the universities, the decline appears to have not yet begun, to judge by the relatively large number of people who continue to write dissertations in which Frye figures importantly. In 1963 Mary Curtis Tucker wrote the first doctoral dissertation on Frye. The period 1964 through 2003 saw another 185 doctoral dissertations devoted in whole or part to Frye, “in part” meaning that “Frye” is indexed as a subject in Dissertation Abstracts International.[11] The number of dissertations for each of the decades falls out as follows: 1960s = 5; 1970s = 28; 1980s = 63; 1990s = 67; 2000–2003 = 23. These data indicate that during the twenty-year period following the height of the poststructural moment interest in Frye as a topic of graduate research has increased rather than diminished. During the 1980s and 1990s he figured importantly in more than six dissertations per year and for the years 2000–2003, eight per year. In 2003, Frye was indexed as a subject in twelve doctoral dissertations, which was the highest number for any year, and eight of these have to do with topics treated in the Anatomy—Menippean satire, romance, myth, genre theory, typological imagery.[12]

Other indicators also suggest increased academic attention to Frye. When Northrop Frye: An Annotated Bibliography was published in 1987, there were eight books devoted in their entirety to his work. Since that time another twenty-four have appeared.[13] The bibliography recorded 588 essays or parts of books devoted to Frye, written over the course of forty years. Since that time, more than 900 additional entries (excluding the hundreds of news stories about Frye and reviews of his books) have been added to the bibliography. In other words, during the past seventeen years a great deal more has been written about Frye than in the previous forty or so years. Of the seventeen symposia and conferences devoted to his work, which have taken place on four continents, thirteen have occurred since 1986: two have been held in China, two in Australia, two in the U.S., five in Canada, one in Italy, and one in Korea.[14] The Anatomy has been continuously in print for forty-eight years (the fifteenth printing by Princeton University Press appeared in 2000), and it has been translated into fifteen languages (see Appendix 1). The last six, two of which are in Arabic, were published after 1990.[15] It appears, then, that for a large number of readers the Anatomy has not faded away. Graham Good remarks that “[t]his is a wintry season for Frye’s work in the West” and that “the once-great repute of the Wizard of the North is now maintained only by a few Keepers of the Flame,”[16] the Keepers of the Flame being apparently the editors of the Collected Works of Frye. But as the Frye bibliography indicates, there are a number of readers beside the Keepers of the Flame who continue to find Frye worthy of attention.[17] Even a poststructuralist like Jonathan Culler has come around to granting that Frye’s vision of a coherent literary tradition is something devoutly to be wished for literary studies.[18] As for Frye’s status outside the universities, Frye is “the only critic,” according to A.C. Hamilton, who addresses a wide reading public.”[19]

The ends and means of the Anatomy have been widely examined and debated, and it is not necessary to review here the scope of the commentary that the book has generated over the years, a large part of which has been recorded.[20] It might be useful, however, to consider some of the less well-known contexts in the history of the Anatomy—its genesis, its initial reception, and its relation to Frye’s earlier and later work, particularly Fearful Symmetry at the beginning of Frye’s career and the religious themes that emerge so clearly in the writings of the last decades of his life. Along the way we will glance at the diagrammatic way of thinking that characterizes Frye’s brand of structuralism and the meaning of the word “anatomy.” We will also consider the relationship of the Anatomy to the critical tradition out of which it emerged (the New Criticism, Neo-Aristotelianism, and comparative anthropology) and its relation to some of the movements in criticism that appeared after the waning of structuralism—largely deconstruction and cultural studies. A full account of these historical contexts is beyond the scope of an introduction, but there may be some value in glancing at the intellectual milieu of the Anatomy‘s birth and the first fifty years of its life.

Frye as Bricoleur

Anatomy of Criticism was many years in the making, and much of it was assembled from the extensive inventory of Frye’s previous writing, published and unpublished. Some of its principal arguments can even be traced back to the essays Frye wrote as student at Victoria and Emmanuel Colleges (1929–1936). The Anatomy, then, can be seen as what Claude Lévi-Strauss calls a bricolage. In The Savage Mind Lévi-Strauss explains that mythical thought is a kind of intellectual bricolage, the bricoleur being one who draws from a “heterogeneous repertoire” and always makes do with “whatever is at hand,” part of which is “the remains of previous constructions.”[21]

Anatomy of Criticism is a book derived from a large heterogeneous repertoire, made from whatever had been left over from Frye’s other jobs, and built at least in part from the residue of previous constructions. The “heterogeneous repertoire” needs little commentary. All readers of the Anatomy are aware of its richly allusive texture and its wide-ranging references to the Western literary and cultural tradition: the book names some 400 poets, novelists, playwrights, philosophers, and artists and refers to more than 430 titles of works, alluding to many more. The extent to which Frye is a bricoleur is suggested in the “Prefatory Statements” to the Anatomy where he lists fourteen essays, written over a twelve-year period, that he revised, expanded, and incorporated into the Anatomy (vii–viii).[22] He was adept at using, in Lévi-Strauss’s phrase, “whatever is at hand.”[23] He not only borrowed liberally from the fourteen published articles but also “transplanted a few sentences from other articles and reviews” (viii).[24] Moreover, he cribbed from his own unpublished papers. One example is “The Literary Meaning of “Archetype,'” a talk presented in 1952 at the annual convention of the Modern Language Association but which remained unpublished for fifty years.[25] Because each paragraph of this talk made its way into the Second Essay of the Anatomy, there can be little doubt that Frye had the paper in front of him when he was writing his “Theory of Symbols.” It served the same blueprint function as the well-known “The Archetypes of Literature” (1951) served for the Second and Third Essays.[26] The earliest of the previously published essays that Frye adapted for the Anatomy are both from 1942, “Music in Poetry,” which he lists in his preface, and “The Anatomy in Prose Fiction,” [27] which he does not, no doubt because this essay, written before he turned thirty, was incorporated into another of his self-pirated pieces, “The Four Forms of Prose Fiction” (1950).

Revealingly, in The Great Code Frye associates bricolage with the anatomy as a prose genre, and Frye says that both the Bible and his own book on the Bible are works of bricolage.[28] He writes that “myth-making has a quality that Lévi-Strauss calls bricolage, a putting together of bits and pieces out of whatever comes to hand. Long before Lévi-Strauss, T.S. Eliot in an essay on Blake used practically the same image, speaking of Blake’s resourceful Robinson Crusoe method of scrambling together a system of thought out of the odds and ends of his reading. I owe a great deal to this essay.”[29] Frye goes on to say that bricolage is the typical poetic procedure, one used not just by Blake and Eliot, but by Dante as well. As it relates to criticism rather than poetry, the focus of bricolage is not on the bits and pieces themselves, but on the system or structure that is built from whatever is at hand. This process, for Lévi-Strauss, is what distinguishes mythical from scientific thought,[30] and the interest in the structure provides the link for Frye between the bricoleur and the anatomist. “Both the scientist and the ‘bricoleur,'” writes Lévi-Strauss,

might . . . be said to be constantly on the look out for “messages.” Those which the “bricoleur” collects are, however, ones which have to some extent been transmitted in advance—like the commercial codes which are summaries of the past experience of the trade and so allow any new situation to be met economically, provided that it belongs to the same class as the other one. . . . [T]he characteristic feature of mythical thought, as of “bricolage” on the practical plane, is that it builds up structured sets, not directly with other structured sets but by using the remains and debris of events.[31]

If we were to substitute “literary conventions” for “codes” and “events” in Lévi-Strauss’s account of the bricoleur, we would describe a process quite similar to the one undertaken by Frye in constructing the Anatomy.

In the preface to the Anatomy Frye indicates that his theoretical interests displaced what he had originally planned to write following Fearful Symmetry (1947), a work of practical criticism on Spenser’s Faerie Queene. The Spenser book was to be one of two volumes he proposed to complete during his Guggenheim fellowship year at Harvard (1950–51). This was all part of an anticipated three-volume project: a study of the Renaissance epic with special attention to Spenser, a study of Shakespearean comedy, and a third volume that, Frye says, “does not enter into my plans at present.”[32] The third volume would emerge eight years later as Anatomy of Criticism. In Fearful Symmetry Frye had shown that Blake was a typical poet, and he had claimed that if we follow Blake’s “own method, and interpret this in imaginative instead of historical terms, we have the doctrine that all symbolism in all art and all religion is mutually intelligible among all men, and that there is such a thing as an iconography of the imagination” (420; CW.14, 407). But, as we learn in Frye’s Guggenheim application, Blake proved to be too isolated a poet for Frye to complete his larger theoretical ambition,[33] and it proved difficult, as Frye says in an interview, to disentangle the “various pieces of insight” about the structure of literature as a whole from his study of Blake.[34] As it turned out, he abandoned his plans for the first two volumes, turning his attention more exclusively to analyzing the features of the “iconography of the imagination.” In the preface to the Anatomy he remarks that the Spenser book began expanding into a theory of allegory, which was connected with larger theoretical issues, and he adds: “I soon found myself entangled in those parts of criticism that have to do with such words as ‘myth,’ ‘symbol,’ ‘ritual,’ and ‘archetype,’ and my effort to make sense of these words in various published articles met with enough interest to encourage me to proceed further along these lines” (3).

By 1950 Frye had already made some headway with these articles, and even in 1949 he was already looking beyond Spenser.[35] As he noted in his Guggenheim application, submitted in October 1949:

Implicit in my study is an attitude to criticism which is being explicitly stated in a series of essays I am now engaged in writing. I regard literary criticism as a science temporarily deprived of its scientific status by a deficiency of theory. Attempts at critical theory have usually relied on philosophy instead of on an inductive survey of literature itself. My present project contains, first, a theory of verbal meaning which tries to unite traditional theories of meaning, such as Dante’s scheme of four levels, with modern ideas about symbolism. Second, a theory of literary symbolism which will present all the essential possibilities of literary symbols in a single form, in other words a kind of grammar of symbolism.[36]

At the time, Frye had already written his essays on “The Four Forms of Prose Fiction,” “The Nature of Satire,” “The Argument of Comedy,” and “The Function of Criticism at the Present Time.”[37] Before leaving for Harvard he had written “Levels of Meaning in Literature” at the request of the Kenyon Review. On the basis of this article, Philip Rice, managing editor of the Kenyon Review, wrote to Frye in June 1950, asking for the third time if he would submit an article on the forms of poetry. Frye obliged by writing, shortly after arriving in Cambridge to begin his Guggenheim year, another article, not on the forms of poetry, but “The Archetypes of Literature.” In his diary entry for 15 May 1950 he noted, I “just hope to God I can work out a conspectus of archetypes,” adding that the book on Spenser would be “sunk if I can’t work out a general theory of archetypes” (D, 350). He was beginning to realize that the Guggenheim project was transforming itself into a more theoretical work. “The Archetypes of Literature,” which was written over the course of two or three days, appears to be the impetus he needed:

I’ve started drafting out a tentative plan for my next Kenyon Review paper, assuming they’d be interested in one on archetypes. The opening stages are a fairly beaten track: ritual is pre-conscious & animal, myth conscious & human. Ritual is the vestigial human form of synchronization, & myth begins as an effort to explain it. Ritual eventually finds its rationale in the yearly cycle, & so myth becomes cyclic too. Working along these lines I think I can get to the narrative archetypes, & from there to the cycles, the approximation of the day-night cycle to the sleep-waking one being the entering wedge. That’s fairly standard, but it’s fairly well known too. What isn’t so well known is my famous demonstration of the anatomy of the spiritual world that I astonish my kids [students] with every January. Well, when I’ve got that done, & gone from there to the narrative archetypes of epic, I have another job, & possibly a second article, in hand, namely the working out of my essential thesis that archetypes are the informing powers of poetry. If I can make a passable article out of that the book will be all over but the footnotes.[38]

Frye’s vision for the Anatomy was not “all over but the footnotes” by any means, but by the time he had completed “A Conspectus of Dramatic Genres,” also for the Kenyon Review during his Guggenheim year, he had written eight of the essays incorporated in the Anatomy. The other six followed over the course of the next three years, so that by 1955 the bricoleur had built up the other half of his “structured sets.” It did not take many months to complete the project: Structural Poetics: Four Essays was sent to Princeton in June 1955 and accepted for publication four months later.[39] Princeton asked Frye to consider changing the title and adding a conclusion and a glossary, and he assented.[40] He later changed the title Structural Poetics to Structure as Criticism, but after the editorial staff at Princeton registered its strong opposition to that, he eventually settled on Anatomy of Criticism, one of the thirteen titles that Benjamin Houston, literary editor at Princeton, suggested as possibilities.[41] The book went to press in February 1957 and was released three months later.

Frye as Structuralist

Lévi-Strauss notes that the scientist creates particular objects or events by means of structures and that the bricoleur creates structures by means of particular objects or events,[42] which is another way of distinguishing between the deductive and inductive methods. Frye works both ways. In “The Archetypes of Literature,” he says, “We may . . . proceed inductively from structural analysis, associating the data we collect and trying to see larger patterns in them. Or we may proceed deductively, with the consequences that follow from postulating the unity of criticism. It is clear, of course, that neither procedure will work indefinitely without correction from the other. Pure induction will get us lost in haphazard guessing; pure deduction will lead to inflexible and over-simplified pigeon-holing” (FI, 10). In the Polemical Introduction to the Anatomy Frye writes that he had proceeded deductively and that he has “been rigorously selective in examples and illustrations,” the examples and illustrations coming of course from the extensive inductive survey he had been engaged in from the time he was a young man.

The inductive and deductive methods are analogous in their goals to the practical and theoretical criticism that Frye saw as separate parts of his ogdoad, an eight-book vision that he used as a heuristic device for his life’s work. As with all of his organizing patterns, the ogdoad was never a rigid outline, but it did correspond to the chief divisions in Frye’s conceptual universe over the years, and throughout his expansive notebooks he repeatedly uses a symbolic code to refer to the eight books he planned to write.[43] In Notebook 7, which Frye began writing as the workshop for the book on Spenser, he says that the three books of his Guggenheim project have both an inductive and deductive form. The inductive form will issue in critical commentary on Spenser and Shakespeare and a study of prose. The deductive form, as Frye goes on to project it for the entire ogdoad, will be “a general discussion of the structure of literature and the grammar of criticism. It takes the salient points of structure . . . & outlines the verbal universe, inserting the essential point of the One Word into the stage represented at present by my colloquium paper” [“The Function of Criticism at the Present Time”]. The deductive form is also, in Frye’s plans at this point, “the mythology of literature & the rhetoric of criticism, an integration of the Word,” as well as “the dialectic of literature & the logic of criticism, expounding metaphysics as a part of the verbal universe & the verbum as the λόγος [logos], or the verbal universe as the logical universe” (7.156). All of this is one of the early formulations (1948) of what Frye would systematically pursue in the Anatomy, and he gives the impression, even in the late 1940s, that the structural principles of literary theory—what he calls ” first-level criticism” (7.173)—are what interest him most. “The deductive approach,” he writes, begins with the conceptions of narrative and meaning” (7.183), which conceptions were to become the omnipresent mythos and dianoia of the Anatomy. By the time he had completed about two-thirds of the entries in Notebook 7, it becomes clear that the book on Spenser had receded into the background and that he was forging full steam ahead on his deductive theoretical book. Here is the way he projects it in 1950 or 1951 in Notebook 7:

In the foreground is the new theory, of which the parts are as follows. First, a general introduction, as in my UTQ “Function” article [“The Function of Criticism at the Present Time”]. Second, an analysis of the four levels of meaning, as in the first KR article [“Levels of Meaning in Literature”]. Third, an analysis of the four levels of criticism, an article I am doing now [“The Literary Meaning of ‘Archetype”’]. Fourth, an outline of the problem of archetypes, as suggested by the “Credo” article [“The Archetypes of Literature”]. From here on it’s vaguer . . . . There should be an analysis of scripture. . . . There should be an article on the four major genres, outlining their inter-relationship. How much systematic grammar of symbolism I need to complete this I dunno. . . . I don’t quite see how my “First Essay” [“Towards a Theory of Cultural History”] works out on so small a scale. But it sure would be a bombshell if it did. Can it be that I am only just now writing the opening chapter? This criticism article should logically end in a discussion of narrative meaning: that is, structure & symbolism, the precipitates of my literary anthropology & psychology respectively. If I do this I’m all set. (7.196)[44]

The “structured sets” that Frye had completed in his essays of the 1940s and 1950s were discrete parts, but they had not become a whole. The struggle he went through to organize these various parts so as to achieve a whole, to fill in the blank spaces, and to develop new material, especially the theory of genres, can be traced in the notebooks for the Anatomy and in his diaries from 1950 to 1955. By the beginning of 1952 he had settled on the title of Essay on Poetics (D, 462), and both his 1952 diary and his notebooks of the time are filled with various schemes and outlines, revealing his preoccupation with the shape of the whole that would take, as already said, another three years to complete. Experimenting with numerous ways to organize the book, he had arrived at this table of contents by early 1953:

| Polemical Introduction | |

| Part One: Table of Literary Elements. | |

| Chapter One: Symbols. | Modes |

| Chapter Two: Modes. | Symbols |

| Chapter Three: Archetypes. | — |

| Part Two: Episodic Forms. | |

| Chapter Four: Specific Forms of Drama. | Encyc. Forms |

| Chapter Five: Specific Forms of Lyric. | Genres |

| Part Three: The Sequence of Continuous Forms. | |

| Chapter Six: Scripture, Romance and Epic. | Rhet. |

| Chapter Seven: Prose Fiction | |

| Chapter Eight: Satire & the Comminution of Forms. | |

| Tentative Conclusion | (35.69) |

The right-hand column, added later, is close to what finally emerged, the separate chapters on encyclopedic forms, genres, and rhetoric (or chapters 4 through 8 in the left-hand column) eventually being collapsed to form the Fourth Essay.

Toward the end of Notebook 7, in an entry dated 1957, Frye wrote, “Anatomy of Criticism has finally been excreted, or crystallized, from these hunches” (7.252), these hunches being the previous seventy or so entries where he experiments with other plans, constructs seven diagrams, and begins to fill in the substance of the various parts of the book—at which point he immediately begins planning his next project. But these seventy entries in Notebook 7 amount to less than one-quarter (about 10,000 words) of the notebook material. There are seventeen notebooks devoted to the Anatomy, written during the ten years after the publication of Fearful Symmetry (1947), and they amount to some 130,000 words altogether, which is almost as many words as in the Anatomy itself.[45] They represent an incessant mental fight to mould the “structured sets” into a whole, which required numerous strategic regroupings of his material and numerous containing forms.

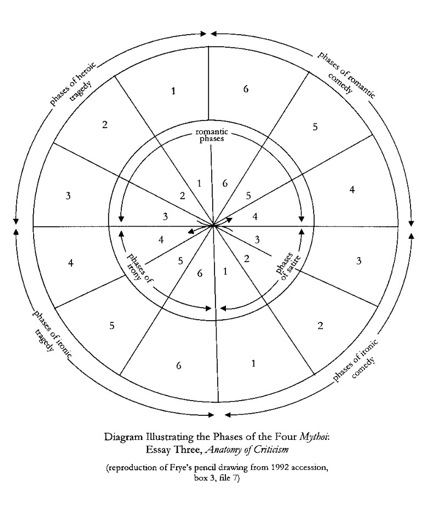

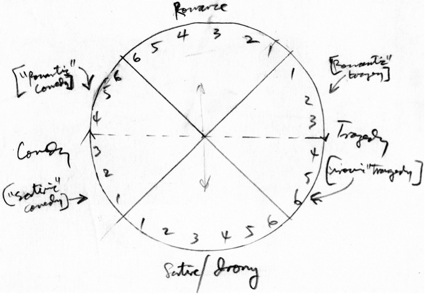

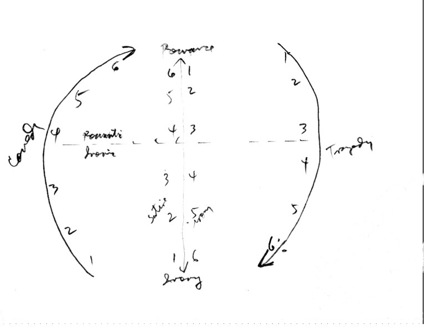

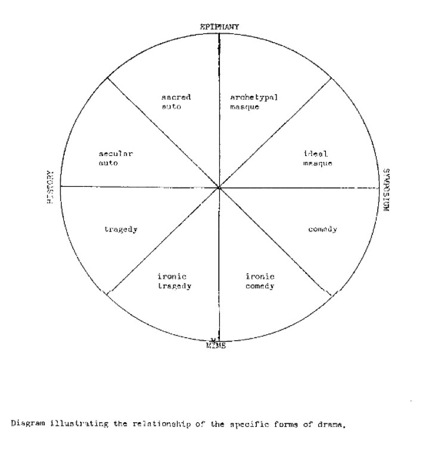

No one reads the Anatomy and most of Frye’s other work without an awareness that he proceeds from what we have been calling the deductive frameworks—hypothetical sets of principles that are often schematic or diagrammatic. Seen from this perspective, his work has moved beyond bricolage: deductive frameworks always assume the sense of the whole. These frameworks, often dialectical, take many forms in the Anatomy: they are based on such oppositions as space and time, mythos and dianoia, melos and opsis, fictional and thematic. Other schema are tripartite, such as the beauty–goodness–truth triad at the beginning of the Fourth Essay, the implications of which Frye began to develop when he was twenty-three.[46] Still others form a vertical hierarchy: the great chain of being or axis mundi. As Frye says in the Anatomy, “Very often a ‘structure’ or ‘system’ of thought can be reduced to a diagrammatic pattern—in fact both words are to some extent synonyms of diagram. A philosopher is of great assistance to his reader when he realizes the presence of such a diagram and extracts it, as Plato does in his discussion of the divided line. We cannot go far in any argument without realizing that there is some kind of graphic formula involved” (314). In his notebooks Frye drew scores of such graphic formulas. The notebooks for the Anatomy contain fourteen diagrams and ten charts or tables. Some of Frye’s schema are quite simple, like the personal/intellectualized and extroverted/introverted set of principles that yields the four forms of prose fiction (288-9). Others are mind-bogglingly complex, such as the one underlying the phases of the mythoi in the Third Essay, a diagram that Frye himself sketched on several occasions in his notebooks. Here are three examples of his diagrams of the four mythoi:

Except for the table of apocalyptic categories in the Third Essay (134) the Anatomy contains no diagrams or summarizing charts, although Frye did include two diagrams and one table in the manuscript he originally submitted to Princeton.[47] But the Anatomy contains dozens of implicit diagrams, and many of Frye’s readers, the present one included, have tried to represent these diagrammatically. Some commentators have protested that the diagramming of Frye’s thought freezes it into a rigid pattern and does not permit the deeper comprehension to emerge. The protest is legitimate if the various schema are taken to be something other than spatially represented summaries of what Frye’s prose presents in a continuous linear form, functioning as aids to comprehension. Yet for Frye himself diagrams were more than this. They were, first, a part of the discovery process for him and, second, a way of representing what he held in his memory theatres. They served, moreover, as a shorthand method for signifying patterns of literary conventions, and they were as well a teaching device, as the countless students who watched Frye draw his patterns on the blackboard can attest. Critical thinking is schematic because poetic thinking is, a point he repeatedly makes in Fearful Symmetry and elsewhere. In his early efforts to understand Blake’s system of thought Frye writes, “the schematic, diagrammatic quality of Blake’s thought was there, and would not go away or turn into anything else”—this coming from an essay that has five diagrams itself.[48] As Frye says in connection with the ingenious diagrams that people sent him over the years, a mandala is not something to stare at but “a projection of the way one sees” (SM, 117). In this respect, Frye’s diagrams, whether implicit or actually drawn, are no different from Plato’s divided line or the implict Linnaenean chart in the first five chapters of Aristotle’s Poetics.

Frye used several large diagrammatic frameworks to structure his imaginative universe. One he called the Great Doodle, a schematic representation of the cyclical quest with its quadrants, cardinal points, and epiphanic sites, as well as the vertical ascent and descent movements along the chain of being or the axis mundi. A part of the Great Doodle was the Hermes-Eros-Adonis-Prometheus (HEAP) scheme that begins in Notebook 7, an Anatomy notebook from the late 1940s, and that dominates the notebook landscape of Frye’s last decade. The HEAP scheme in its half-dozen variations is used to define the quadrants of the Great Doodle, and there are countless other organizing devices, serving as Lesser Doodles, that Frye draws from alchemy, the zodiac, musical keys, colors, the chess board, the omnipresent “four kernels” (commandment, aphorism, oracle, and epiphany), the shape of the human body, Blake’s Zoas, Jung’s personality types, Bacon’s idols, the boxing of the compass by Plato and the Romantic poets, the greater arcana of the Tarot cards, the seven days of Creation, the three stages of religious awareness, and numerological schemes.[49] Frye used these frameworks to organize and structure his imaginative universe. Structure is an architectural metaphor, and the building that emerges from the structure is a literary theory, as Frye reminds us in the final sentences of the Polemical Introduction.[50] There Frye also says, in an apparent rhetorical appeal to those not given to schematics, that he attaches no importance to the schematic form itself, adding that much of it “may be mere scaffolding, to be knocked down when the building is in better shape” (30). It is difficult to take Frye seriously here and no less difficult to imagine what Anatomy of Criticism would look like without its schematic form.[51]

Frye as Anatomist

Schema, of course, spring from analysis or dissection, which is one meaning of the word “anatomy.” As already indicated, Frye associates the technique of bricolage with the form of fiction he called anatomy: “In a way I have tried to took at the Bible as a work of bricolage, in a book which is also that. I retain my special affection for the literary genre I have called the anatomy, especially for Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, with its schematic arrangements that are hardly those of any systematic medical treatment of melancholy, and yet correspond to something in the mind that yields a perhaps even deeper kind of comprehension” (The Great Code, 13). In connection with representing these schema visually, Frye goes on to say that in The Great Code he has “been more liberal with charts and diagrams than usual” (ibid.). In that book he inserts eleven charts, diagrams, and tables and in Words with Power five more. Anatomizers do not simply dissect; they name and arrange the parts. In this respect, they become taxonomists, and Frye is of course our greatest literary taxonomist, one who, in the literal sense of the word, develops a method of arrangement. But for Frye anatomizing involves synthesis as well as analysis, or rather analysis in the service of a “synthetic overview.”

The word anatomy in Shakespeare’s day and a little later meant a dissection for a synthetic overview. One of my favorite books in English literature—there are times when it is actually my favorite—is Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy. Of course, there were four humors then, but for Burton there was only the one, melancholy. That was the source of all mental and physical diseases in the world. So he writes an enormous survey of human life. It ranks with Chaucer and Dickens, except the characters are books rather than people. It was both an analysis of the causes and cures and treatment of melancholy and a kind of synthetic overview of human nature before it gets melancholy. On a much smaller scale there was Lyly’s Euphues: The Anatomy of Wit, which has given us the word euphuism, meaning that if you’re too bright and don’t know enough you can get into trouble. That use of the term anatomy was one that I thought exactly fitted what I was doing.” (Northrop Frye in Conversation, 69)

If Frye intended his anatomy to be like Burton’s in combining analysis and synthesis, he also intended it to be comprehensive.[52]

The word “anatomy” in Frye is of course a pun, referring both to a form of prose fiction and to his own work of criticism. “The Anatomy in Prose Fiction” (1942), already mentioned, was his first major published essay. But the possibility of the anatomy as a separate class of prose had been entertained by Frye at least five years earlier. In a 1937 letter, he wrote to Helen Kemp that he had read his “anatomy paper” to his Oxford tutor Edmund Blunden” (The Correspondence of Northrop Frye and Helen Kemp, 2:693). This may have been, or been a version of, one of Frye’s student essays that has survived, “An Enquiry into the Art Forms of Prose Fiction” (Northrop Frye’s Student Essays, 383–400). In any event, the paper we have, which dates from the late 1930s, is the earliest of his several accounts of the anatomy before the publication of Anatomy of Criticism, and is clearly the blueprint for “The Anatomy in Prose Fiction.”

In Frye’s student essay the anatomy is seen as related to fiction and drama but differing from them in its effort to build up an argument or attitude. It is similar to the essay in its interest in ideas: the essay develops an idea, while the anatomy interweaves a number of ideas. Because anatomy is a literary term, it can apply to any kind of writing in any field that has survived because of its literary value. Anatomies reveal the interests or outlooks of the author, as in satires and Utopias or other abstract, conceptual, or generalized attitudes to human personality or society. Such interests are prior to the strict requirements of philosophy or psychology. Anatomies always reveal an intellectual interest, and they display their authors’ erudition. They begin, Frye writes, in the Renaissance with Cornelius Agrippa’s Vanity of the Arts and Sciences, followed by Erasmus’s Encomium Moriae, More’s Utopia, and Castiglione’s Courtier. On the continent, the culminating development is Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel, and in England Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy (Northrop Frye’s Student Essays, 390–1).

Many of Frye’s insights came to him early, and his “discovery” of the anatomy is one example. He was in his mid-twenties when he wrote “An Enquiry,” and the features of the anatomy outlined there were not substantially altered in his subsequent treatments of the form, culminating in his expanded definition of the genre in the Fourth Essay of the Anatomy. What does appear in his subsequent treatments is an effort to trace the beginning of the anatomy back beyond the Renaissance to the Classical Mennipean satire, which is a subspecies of the anatomy.[53]

The question naturally arises, What does it mean to say that Frye’s Anatomy is itself an anatomy? It is obviously not a work of prose fiction, but it does contain a number of characteristics of the anatomy as a literary form: it is an intellectualized form and thus focuses on dianoia rather than ethos; it builds up integrated patterns; it has a theoretical interest; it embraces a wide variety of subtypes; it displays considerable erudition; its schematic form is an imaginative structure, born of an exuberant and creative wit; and whatever dramatic appeal it has comes from the dialectic of ideas. Frye’s Anatomy is of course not satire, which combines fantasy and morality often with the deprecating quality as found in, say, Lyly’s The Anatomy of Wit, but embedded in its Utopianism is a clear moral attitude. If Frye, as an implied author, might appear to be obsessed with his entire intellectual project, he does not qualify as a philosophus gloriosus or a learned and pedantic crank—often the object of satire in the anatomy.

The main difference between the Anatomy and other anatomies, however, is in their differing final causes. Frye always insisted that the lines between the critical and the creative should not be sharply drawn, and he remarks in one of his Anatomy notebooks, “In poetics we often have to speak poetically” (35.51). But for all of its aesthetic appeal—its creativity and ingenuity, its wit and stylistic charm, its inventive taxonomies—the Anatomy remains a work of criticism, in spite of those, such as M.H. Abrams and Frank Kermode, who claim otherwise, mistaking the means for the end.[54] The Anatomy comes to use primarily in what Frye would later call second-phase language, the continuous prose of abstraction and reason and of analogical and dialectical thinking. Its aim, as suggested above, is the analysis of literary conventions and the synthesis of these into comprehensive order.

Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy was ostensibly a medical discourse. Today it is read less for instruction into the cures of the psychiatrically sick than for its delight. Posterity will determine whether Frye’s Anatomy follows the course of Burton’s. So far, fifty years after its publication, it is still read primarily as a work of literary theory, and most of its applications have been in the interest of description, explanation, and interpretation. This is not to gainsay its wit and eloquence, the aesthetic appeal of its formal structure, and its engendering of delight. But none of these things is the final cause of a book Frye saw as a new criticism that went beyond the New Criticism.

Frye and the New Criticism

In his diary entry for 14 March 1950 Frye reports on a party he attended at the home of A.S.P. Woodhouse, where M.H. Abrams, who had been lecturing in Toronto, and Marshall McLuhan, among others, were in attendance. The gossip of the evening included the news that Woodhouse was to deliver a paper on Milton at an upcoming session at the annual meeting of the Modern Language Association and that his historical perspective was to be opposed on the program by Cleanth Brooks, who, Frye writes, “apparently belongs to a group called the ‘New Critics’ who are supposed to ignore historical criticism & concentrate on texture, whatever texture is.” Frye, whose “Levels of Meaning in Literature” appeared in the Spring 1950 issue of the Kenyon Review, then adds, “I asked Abrams if being in the Kenyon Review would make me a new critic: I certainly can’t claim to be au courant in such matters” (Northrop Frye’s Diaries). Three months later he learns that people in the United States are referring to him as a new critic.[55] These are the earliest references in Frye’s work to the New Criticism.

Although later in the year (June 1950) Frye refers to a Toronto master’s thesis as “a new critical analysis,”[56] he nevertheless appears at this time to have been genuinely naive about the burgeoning critical orthodoxy known as the New Criticism. John Crowe Ransom had founded the Kenyon Review in 1939 and had published The New Criticism two years later. Cleanth Brooks, in collaboration with Robert Penn Warren, had published his Understanding Poetry in 1938 and Understanding Fiction in 1943, both of which, for literary studies, turned out to be the most influential teaching manuals of the next several decades.[57] W.K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley had published “The Intentional Fallacy” (1946) and “The Affective Fallacy” (1946), arguing the centripetal and formalist position that it is misleading for the critic to assume that poetry is, respectively, a record of the private experience of the poet and an account of the private experience of the reader. Brooks’s “The Heresy of Paraphrase” had appeared in 1947. At the time of his diary entry Frye seems to have been innocent of these new critical beginnings, and innocent as well of the work of I.A. Richards and R.P. Blackmur and of René Wellek and Austin Warren’s New Critical bible, Theory of Literature (1949).[58] But it did not take him long to discover the ball park in which the game was being played.

In 1950 John Crowe Ransom, the editor of the Kenyon Review, invited a group of well-known critics to contribute to a series of essays called “my credo.” William Empson’s “The Verbal Analysis” was the first of the series. In 1951 Cleanth Brooks contributed “My Credo: Formalist Critics.” Whether Frye ever read Empson’s essay is uncertain. He had read Empson’s Seven Types of Ambiguity in the 1930s, though without associating it with an identifiable critical practice (RW, 180). But he certainly would have been familiar with Brooks’s “credo,” which appeared in the same issue of Kenyon Review as “The Archetypes of Literature.”[59] During the next four or five years, Frye came to understand what the New Critical enterprise was all about, though there is no evidence that he read any of the major New Critical documents except Richards’s Practical Criticism and some unnamed essays by Blackmur.[60] His knowledge of the New Critics came primarily from R.S. Crane, who gave the Alexander Lectures at the University of Toronto during the Easter term of 1952. These lectures were published as The Languages of Criticism and the Structure of Poetry (1953), and Frye reviewed the book for the University of Toronto Quarterly in 1954, having critiqued the collection of essays by the Chicago Aristotelians— Critics and Criticism—several months earlier.[61] Frye’s designation of the New Critics as “rhetorical critics” came from Crane, who saw the New Critics as the latest incarnation of the rhetorical tradition in Western criticism that began with Horace. Frye’s understanding of these critics derived in considerable measure from chapter 4 of The Language of Criticism and the Structure of Poetry and from the appraisals, largely negative, of Richards, Empson, Brooks, Robert B. Heilman, and Robert Penn Warren by Crane, Elder Olson, and W.R. Keast in Critics and Criticism.[62]

What then was the position of the New Critics who were fairly well established before they were discovered by Frye about halfway through his writing of the Anatomy? The New Criticism was more a movement than a school—a body of ideas about the nature of literature and a method of reading literary texts. Among its more immediate forebears was T.S. Eliot, with his impersonal theory of poetry and his dictum that literature was autonomous—poems should be read as poems and not something else. The notion that poetry is an organic whole that reconciles opposite or discordant qualities was a New Critical tenet, one that can be traced back to chapter 13 in Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria.[63] The word “organic” tended to drop out of the New Critics’ vocabulary, but the idea of unity persisted, as in Brooks’ formulation: “the primary concern of criticism is with the problem of unity—the kind of whole which the literary work forms or fails to form, and the relation of the various parts to each other in building up this whole.”[64] In addition to the principles of autonomy and unity, the New Critics privileged the literary qualities of irony, paradox, and ambiguity, and they saw the literary work as a unique object for rapt attention. This led to their emphasis on the close reading of texts, as in Empson’s Seven Types of Ambiguity, Brooks’s The Well-Wrought Urn, and Robert Penn Warren’s reading of Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.[65]

By the mid-1950s Frye had picked up on these new New Critical doctrines and practice, and they shortly came to inform the background of his theory of symbols in the Anatomy. In the Second Essay he develops a taxonomy of the phases of symbolism, each phase having an affinity to both a certain kind of literature and a typical critical procedure. This relation for the descriptive and literal phases of literature (Dante’s literal level in the medieval scheme) can be represented by a continuum running from documentary naturalism at one pole to symbolisme and “pure” poetry at the other. Although every work of literature is characterized by both these phases of symbolism, there can be an infinite number of variations along the descriptive-literal axis, since a given work tends to be influenced more deeply by one phase than the other. Thus when the descriptive phase predominates, the narrative of literature tends toward realism, and its meaning toward the didactic or descriptive. The limits, at this end of the continuum, would be represented by such writers as Zola and Dreiser, whose work “goes about as far as a representation of life, to be judged by its accuracy of description rather than by its integrity as a structure of words, as it could go and still remain literature” (73). At the other end, as a complement to naturalism, is the tradition of writers like Mallarmé, Rimbaud, Rilke, Pound, and Eliot. Here the emphasis is on the literal phase of meaning: literature becomes a “centripetal verbal pattern, in which elements of direct or verifiable statement are subordinated to the integrity of that pattern” (ibid.). Criticism, says Frye, was able to achieve an acceptable theory of literal meaning only after the development of symbolisme (ibid.).

In a similar fashion, the literal and descriptive phases are reflected in two chief types of criticism. Frye’s classification of the forms of criticism, in relation to the entire schema of his theory of symbols, can be represented diagrammatically, as follows:

| The Phases of Symbolism | |||||

| LITERAL | DESCRIPTIVE | FORMAL | MYTHICAL | ANAGOGIC | |

| TYPE OF SYMBOL | Motif | Sign | Image | Archetype | Monad |

| NARRATIVE (MYTHOS) |

Rhythm or movement of words; flow of particular sounds | Relation of order of words to life; imitations of real events | Typical event or example

Shaping principle |

Ritual: recurrent act of symbolic communication | Total human ritual, or unlimited social action |

| MEANING (DIANOIA) |

Pattern or structural unity; ambiguous and complex verbal pattern | Relation of pattern to assertive propo-sitions; imitation of objects, propositions | Typical precept

Containing principle |

Dream: conflict of desire and reality | Total dream, or unlimited human desire |

| RELATED KIND OF ART | Symbolisme | Realism and naturalism | Neoclassical literature | Primitive and popular writing | Scripture, apocalyptic revelation |

| RELATED KIND OF CRITICISM | “Textural” or New Criticism | Historical and documentary criticism | Commentary and interpretation | Archetypal criticism (convention and genre) | Anagogic criticism (connected with religion) |

| MEDIEVAL LEVEL | Literal or historical | Allegorical | Moral or tropological | Anagogic | |

| PARALLEL MODE FROM FIRST ESSAY | Thematic irony | Low mimesis | High mimesis | Romance | Myth |

Here we see that Frye relates the descriptive aspect of a symbol to the various kinds of documentary criticism that deal with sources, historical transmission, the history of ideas, biographical study, and philological investigation. Such Wissenschaft approaches assume that a poem is a verbal document whose “imaginative hypothesis” can be made explicit by assertive or propositional language. Documentary criticism is the form of criticism that dominated literary studies before the arrival of the New Criticism. What such criticism tended to document were moral and philosophical topoi in the history of ideas or biographical and historical causes. The limitations faced by documentary critics, as Frye would later write, were three:

In the first place, they do not account for the literary form of what they are discussing. Identifying Edward King and documenting Milton’s attitude to the Church of England will throw no light on Lycidas as a pastoral elegy with specific Classical and Italian lines of ancestry. Secondly, they do not account for the poetic and metaphorical language of the literary work, but assume its primary meaning to be a nonpoetic meaning. Thirdly, they do not account for the fact that the genuine quality of a poet is often in a negative relation to the chosen context. To understand Blake’s Milton and Jerusalem it is useful to know something of his quarrel with Hayley and his sedition trial. But one also needs to be aware of the vast disproportion between these minor events in a quiet life and their apocalyptic transformation in the poems. (The Critical Path, 19–20)

A literal (first phase) criticism, as opposed to descriptive (second phase) criticism, would find in poetry “a subtle and elusive verbal pattern” that neither leads to nor permits simple assertive statements or prose paraphrases. As Frye’s language here suggests, this tendency is represented by New Criticism, an approach based

on the conception of a poem as literally a poem. It studies the symbolism of a poem as an ambiguous structure of interlocking motifs; it sees the poetic pattern of meaning as a self-contained “texture,” and it thinks of the external relations of a poem as being with the other arts, to be approached only with the Horatian warning of favete linguis, and not with the historical or the didactic. The word texture, with its overtones of a complicated surface, is the most expressive one for this approach. (75)

Frye’s indebtedness to the terms and distinctions of the New Critical poetics is obvious here. In fact, he says in a note that his account of ambiguity derives from I.A. Richards, R.P. Blackmur, and William Empson, of literal irony from Cleanth Brooks, and of texture from John Crowe Ransom.[66] The principal assumption underlying Frye’s analysis of the descriptive and literal phases of symbolism is one he shares with these critics—that the meaning of poetry is found in the nature of its symbolic language. Frye’s distinction between assertive and hypothetic meaning is closely akin, for example, to opposition in Brooks between factual and emotional language; to I.A. Richards’s emotive-referential dialectic; to the distinction in John Crowe Ransom between rational and poetic meaning, or in Philip Wheelwright between steno-language and depth-language; to the opposition in Empson between clarity and ambiguity; or, finally, to the procedure running throughout contemporary criticism, which attempts to separate poetic language from that of either ordinary usage or science on the basis of the more complex, ambiguous, and ironic meaning of the former. The characteristic method of inference in each of these procedures is based on a similar dialectic; for they all, Frye included, employ a process of reasoning to what the language and meaning of poetry are from what assertive discourse and rational meaning are not.[67]

Frye refused to accept the semantic analysis of logical positivism, that is, the reduction of all meaning to either rational or emotional discourse.

Some philosophers who assume that all meaning is descriptive meaning tell us that, as a poem does not describe things rationally, it must be a description of an emotion. According to this the literal core of poetry would be a cri de coeur, . . . the direct statement of a nervous organism confronted with something that seems to demand an emotional response, like a dog howling at the moon. . . . We have found, however, that the real core of poetry is a subtle and elusive verbal pattern that avoids, and does not lead to, such bald statements. (74–5).

While it is true that the subtlety and the range of reference in Frye’s discussion of the literal phase will not permit a simple equation between the meaning expressed by symbols in this phase and the nondescriptive meaning of the analytic philosophers, it is no less true that he still remains within the framework of the theory he opposes; what he does is to convert his denial of the principles of linguistic philosophy into the principles of his own poetic theory. The primary assumptions remain the same: poetry, in the literal and descriptive phases, is primarily a mode of discourse, and there is a bipolar distribution of all language and thus all meaning.

The first section of Frye’s theory of symbols, as shown in the chart above, requires an expansion and rearrangement of Dante’s medieval scheme of four levels of interpretation, according to which literal meaning is discursive or representational meaning. Its point of reference is centrifugal. When Dante interprets scripture literally, he points to the correspondence between an event in the Bible and a historical event, or at least one he assumed to have occurred in the past. In this sense, literature signifies real events. The first medieval level of symbolism thus becomes Frye’s descriptive level. His own literal phase, however, has no corresponding rung on the medieval ladder. The advantage of rearranging the categories, Frye believes, is that he now has a framework to account for a poem literally as a poem—as a self-contained verbal structure whose meaning is not dependent upon any external reference. This redesignation is simply one more way that Frye can indicate the difference between a symbol as motif and sign. As a principle of Frye’s system, it reveals the dialectical method he uses to define poetic meaning. He is not satisfied, however, with the dichotomy, calling it a “quizzical antithesis between delight and instruction, ironic withdrawal from reality and explicit connection with it” (76).

It is against the backdrop of the literal and descriptive phases of symbolism that Frye moves beyond the New Critical position by positing the existence of three additional phases: the formal (Dante’s allegorical level), the mythical (Dante’s moral or tropological level), and the anagogic (Dante’s fourth level). As Frye’s central interest in the Anatomy is archetypal criticism, he devotes almost all of his attention in the last two essays to those topics summarized in the fourth and fifth columns of the chart above. He does not consider his analysis of myth and archetype as replacing either historical criticism or the New Criticism. All forms of serious critical inquiry are legitimate: they fall under the umbrella of his conception of a pluralism of critical methods, including anagogic criticism, to which, as we will see, Frye devotes a great deal of attention toward the end of his career. Our focus here has been on the first two phases of symbolism. Later we will consider the theory of phases in a broader context.

To summarize Frye’s indebtedness to the New Critics: he accepts their assumptions of literary autonomy and poetic unity,[68] and he accepts the view that the poetic use of language is different from its other uses. Yet Frye was aware of the excesses and limitations of the New Criticism, as we see from his several retrospective accounts of the movement. First, the New Critics deprived the literary work of any sense of context, even the historical context of the documentary critics. Second, it failed to build up any connecting links among the poems it explicated. Third, in its emphasis on the poetic object worked against the ideal goal of literary study, which is the reader’s possession of the literature. Fourth, its approach to explication in terms of the lyric qualities of a work, whatever its genre, tended to limit its focus by elevating the writers of discontinuous intensity, such as Keats, Hopkins, Rimbaud, and Hölderlin, above the great tradition of continuous writers, such as Spenser, Milton, Goethe, and Hugo. And fifth, the emphasis on poetic texture tended to exclude poetic structure.[69] While Frye is thus indebted to the New Critical currents of the time, he sees their limitations, and the Anatomy seeks to go beyond them with its emphasis on literary structure and on the larger context of literature as a whole, the conventions of which link literary works to each other. Without this larger view, the critical task is reduced to adding more and more explications to the critical tradition with nothing to connect the separate commentaries.

Frye and the Chicago Neo-Aristotelians

What was Frye’s relation to the Neo-Aristotelians, a group of critics centred at the University of Chicago who had begun to receive considerable attention during the time Frye was writing the Anatomy? As already indicated, Frye was familiar with their essays and with R.S. Crane’s The Languages of Criticism and the Structure of Poetry, and he was invited to lecture in the English department at Chicago two years before the Anatomy was published. The Anatomy, for all of its Platonic sense and sensibility, appears to owe a considerable debt to Aristotle. Frye conceives of his project as developing a new Poetics, and its chief organizing principles derive from Aristotle’s terms for the six qualitative parts of tragedy: mythos, ethos, dianoia, melos, lexis, and opsis. Frye greatly expands the meanings of these terms from their very specific meaning in Aristotle (much to the chagrin, no doubt, of the literal-minded Aristotelians), but they served him well as a tool for organizing his material.[70] Mythos, which Frye generalized to mean any kind of temporal movement, and dianoia, which came to represent any form of spatial organization, served as primary deductive principles for the rest of his career. As one might expect, Frye had a long-standing interest in Aristotle: his first reference to the Poetics appears in a student essay he wrote in 1936 (Northrop Frye’s Student Essays, 333). But it is clear from his notebooks for Anatomy of Criticism that Frye’s knowledge of the Poetics is significantly indebted to his reading of the Chicago critics, even if he sometimes takes an oppositional stance to their views.

In a 1953 notebook Frye remarks that he derived his original idea about the formal phase of symbolism (the third level) from listening to Crane’s 1952 Alexander Lectures at Toronto (NB 36.2). In the same notebook Frye writes, “Aristotle left the way open for Crane & his school to deduce that in its aspect as imitation of thought (dialectic) poetry is rhetorical & not strictly poetic at all” (NB 36.102). The position of the Chicago critics was that for Aristotle poetry had to do with making and the other “sciences” with knowing (e.g., metaphysics, dialectic) or doing (politics, ethics). Although Aristotle was careful to separate verbal structures according to their final causes, Frye wants to combine them. He therefore takes issue with Crane’s absolute separation of rhetoric and poetics: “as long as you’re dealing with words all verbal structures are imitations of thought, & therefore to that extent even dialectic is rhetorical” (ibid.).

Frye’s reviews of both The Languages of Criticism and the Structure of Poetry and Critics and Criticism are generally sympathetic, and it is clear that his understanding of poetic wholes, the catharsis of pity and fear, imitation, the rhetorical tradition descending from Horace and Cicero through Quintilian, the four-cause method of definition, and the differences between inductive (literal) and deductive (a priori) critical methods is enriched by his having read the Chicago critics on these matters. He calls Critics and Criticism “indispensable for the serious student of criticism” (Reading the World, 127), even though he is not always convinced by their assumptions, principles, and methods. He does not accept, for example, the Chicago school’s unconditional separation of all literature into mimetic and didactic categories, and he does not believe that the Aristotelian concept of action (praxis) should be so favoured as to exclude thought (dianoia): “A well-constructed imitation of an action . . . has a dianoia or thought-form as well as an event-form, or rather, these are two aspects of the same thing. The dianoia is the total internal idea of the poem, and it exists both in mimetic and didactic poetry” (ibid., 128–9). Frye is skeptical as well about any unconditional separation of rhetoric and poetics, and he believes Crane’s method promises more than it delivers (ibid., 133–4).

In the final analysis Frye’s debt to Aristotle, whether based on his own reading of the Poetics or filtered through the Neo-Aristotelians’ interpretation, does not turn out to be constitutive as a first principle in the Anatomy. The influence is fundamentally a matter of the efficient cause, to use the Aristotelian tag. Aristotle’s language is omnipresent, even though, as already said, Frye redefines and adapts it to his own ends. Terms such as dianoia and ethos begin to appear in Frye’s notebooks for the Anatomy only after 1953, the year before his reviews of the Chicago critics appeared. In writing the Anatomy, therefore, Frye seems often to have had the Neo-Aristotelians in the background of his consciousness and sometimes in the foreground. Their work, begun in the 1930s, had emerged in the early 1950s, and without Frye’s awareness of their essays and Crane’s book the shape and the language of the Anatomy would have been considerably different.

Frye between Frazer & Freud: The Grammar of Symbolism

Conspicuous in the summary chart of Frye’s theory of symbols are the words “myth,” “ritual,” “dream,” and “archetype.” These central concepts in the Anatomy were drawn from intellectual currents of thought much broader than those from the world of literary criticism and earlier than those of the New Criticism—comparative anthropology (Frazer and the Cambridge Hellenists), history of cultures (Spengler), mythography (Cassirer), and psychoanalytic theory (Freud and Jung). In one of his notebooks for the Anatomy Frye writes, “This last [chapter] begins with the threefold pattern of art as between action & thought, history & philosophy, law & science, music & painting, & works out all these implications: in fact it strettoes the whole book, & puts Frye between Frazer & Freud (ritual & dream, society & the individual)” (NB 38.85). In what respects did Frye see Frazer and Freud and other mythographers, some of whom he read more than thirty years before the Anatomy was published, as bookends between which his own position took shape?

Frye began to read Frazer toward the end of 1934, when he was studying theology at Emmanuel College. On 19 October of that year he wrote to Helen Kemp, “I’ve started to read the Golden Bough for my Old Testament, which is all about magic in religion, the development of vegetation rites, the symbolic killing and eating of the god, bewailing the death of the god of fertility in the winter and his resurrection in the spring—the Adonis, Osiris, Dionysus and Demeter cults which all synthesise and coalesce in the Passion from Palm Sunday to Easter. It’s a whole new world opening out, particularly as that sort of thing is the very life-blood of art, and the historical basis of art.”[71] Frye immersed himself particularly in four of Frazer’s twelve volumes, The Dying God (vol.4), Adonis, Attis, Osiris (vols. 5 and 6), and The Scapegoat (vol. 9).[72] In one of his autobiographical notes Frye writes, “Theology, to me, meant mostly The Golden Bough.”[73] As it turned out, seven of the essays he wrote for his theology and Bible courses show the imprint of Frazer. In one of those papers he calls The Golden Bough “perhaps the most important and influential book written by an Englishman since The Origin of Species” (Northrop Frye’s Student Essays, 140). What attracted Frye to Frazer was the positive value the latter attached to myth and the implications of The Golden Bough for the study of symbolism. The notebooks for the Anatomy reveal that Frazer, who is referred to more than thirty times, was much on Frye’s mind during the ten years he spent writing the book. Ford Russell has provided the most extensive account of Frazer’s influence on Frye,[74] and in addition to the scores of places in Frye’s own work where Frazer gets mentioned in passing, his 1959 CBC Radio talk on Frazer contains a lively account of Frazer’s importance.

In order to consider what Frye means by placing himself between Frazer and Freud, we need to reflect more broadly on the ends and means of the Anatomy‘s “Theory of Symbols.” In The Critical Path, Frye remarks that his theory of literature was developed from an attempt to answer two questions: What is the total subject of study of which criticism forms a part? and, How do we arrive at poetic meaning? (The Critical Path, 14–15). The latter question is addressed in Second Essay, “Ethical Criticism: Theory of Symbols.” Frye’s starting point is to admit the principle of “polysemous” meaning, which is, as already indicated, a modified version of Dante’s fourfold system of interpretation. Once the principle is granted, he claims, “we can either stop with a purely relative and pluralistic position, or we can go on to consider the possibility that there is a finite number of valid critical methods, and that they can all be contained within a single theory” (66). Frye develops his argument by first placing the issue of meaning in a broader context:

The meaning of a literary work forms a part of a larger whole. In the previous essay we saw that meaning or dianoia was one of three elements, the other two being mythos or narrative and ethos or characterization. It is better to think, therefore, not simply of a sequence of meanings, but of a sequence of contexts or relationships in which the whole work of literary art can be placed, each context having its characteristic mythos and ethos as well as its dianoia or meaning. (67)

Context, then, rather than meaning becomes the organizing principle, and the term Frye uses for the contextual relationships of literature is “phases,” a word we have already encountered, phases being contexts within which literature has been and can be interpreted or perspectives from which to analyze meaning. The word “ethical” in the title of the Second Essay does not derive from the meanings which ethos had in the First Essay: Frye is not concerned here to expand the analysis of “character” found there. The word refers rather to the connection between art and life which makes literature a liberal yet disinterested ethical instrument. Ethical criticism, Frye says in the Polemical Introduction, refers to a “consciousness of the presence of society. . . . [It] deals with art as a communication from the past to the present, and is based on a conception of the total and simultaneous possession of past culture” (25). What provides the connection between the past and the present is the archetype.

Referring to the terms in our chart above, “symbol” is the first of three basic categories Frye uses to differentiate the five phases, the other two being mythos and dianoia. Like many of Frye’s terms, “symbol” has a broad range of reference. In the Second Essay it is used to mean “any unit of any literary structure that can be isolated for critical attention” (65). This broad definition permits Frye to associate the appropriate kind of symbolism with each phase and thereby to define the phase at the highest level of generality. The symbol used as a sign results in the descriptive phase; as motif in the literal phase; as image in the formal phase; as archetype in the mythical phase; and as monad in the anagogic phase.

In an early essay on the nature of symbolism, Frye says that “wherever we have archetypal symbolism, we pass from the question ‘What does this symbol, sea or tree or serpent or character, mean in this work of art?’ to the question ‘What does it mean in my imaginative comprehension of such things as a whole?’ Thus the presence of archetypal symbolism makes the individual poem, not its own object, but a phase of imaginative experience.”[75] Archetypal symbolism works in two directions for Frye. On the one hand, because the language of myth and symbol enters and informs all verbal culture, Frye often used what he learned about symbolism as a literary critic to interpret texts in philosophy, psychology, history, and comparative religion. On the other hand, he sees these disciplines as informing literary criticism itself. Thus, he can approach Toynbee’s Study of History from the centrifugal perspective, seeing it as “an intuitive response based on an imaginative grasp of the symbolic significance of certain data” (Northrop Frye on Culture and Literature, 80). Toynbee’s book can be read, then, not as a factual chronicle that is trying to prove something by its massive accumulation of data but as a grand imaginative vision. Similarly, with Frazer’s Golden Bough, Frye approaches it as if it were an encyclopedic epic or a continuous form of prose fiction. Its subject, he says, is really “about what the human imagination does when it tries to express itself about the greatest mysteries” (ibid., 89). But Frye also works in a centripetal direction. Frazer and a number of other mythographers (Cassirer, Spengler, Jung, and Eliade) are themselves students of symbolism, whose works provide us with a grammar of the human imagination. Cassirer’s symbolic forms, like those found in literature, take their structure from the mind and their content from the natural world. And Frazer’s expansive collections of material, because they give us a grammar of unconscious symbolism on both its personal and its social sides, will be of greater benefit to the poet and literary critic than to the anthropologist. Thus, The Golden Bough, like Jung’s Psychology of the Unconscious, becomes primarily a work of literary criticism. Similarly, Eliade’s studies in Religionsgeschichte are especially important for the literary critic because they provide a grammar of initiatory and comparative symbolism.

The two perspectives—the centrifugal and the centripetal—do not finally move in opposite directions in Frye’s work. They interpenetrate, to use his familiar metaphor. In his review of Jung’s Psychology of the Unconscious, Frye develops a view of criticism which makes its way later, some of it verbatim, into his account of the archetypal phase of symbolism in the Anatomy. But this is not to say that Frye is a Jungian. His view has always been that criticism needs to be independent from externally derived frameworks, what he calls “determinisms” in the Anatomy. “Critical principles cannot be taken over ready-made from theology, philosophy, politics, science, or any combination of these” (8). Yet Frye himself, of course, has appropriated a number of concepts from other disciplines, especially from psychology and anthropology. In the second essay of the Anatomy they appear as ritual and dream. Frye appropriates terminology as well. Three of the four aspects of the monomyth (agon, pathos, and anagnorisis), for example, are borrowed from Gilbert Murray’s account of Greek ritual.[76]