[Mikhail Bakhtin, 1920]

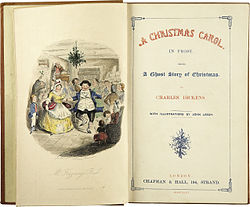

The following is an excerpt, slightly revised, from an essay I wrote some years ago on some of the connections between Frye and contemporary literary theory. A theme that runs through Frye’s pieces on Christmas is the idea of saturnalia or an upside-down world, a season of festivity and carnival common to many cultures. Such a holiday from the “real world’ is the closest we get to a world that makes human sense, when the social hierarchy is reversed and the spirit of fellowship, neighbourliness, and joy, released from an oppresive social structure, becomes, for a brief period of license, the social norm. Elsewhere Frye makes the link between saturnalia and comedy and satire, a link that is central to Mikhail Bakhtin’s theory of the novel and the novelistic.

Frye and Bakhtin: Satire, Saturnalia, and the Carnivalesque

Besides practising the art of anatomy himself, Frye did much to resurrect a sense of the importance of the genre in Western literature, and he regarded it as a crucial, if not, like Mikhail Bakhtin, the most important, element flowing into what we now recognize as the novel. The generic radicals of the novel that he isolates–anatomy, romance, confession, and the novel of personality–are, indeed, more or less analogous to the genetic lines that Bakhtin comes up with in “The Forms of Time and Chronotope in the Novel.”

Bakhtin and Frye are also in agreement in refusing to analyze satire outside of a larger mythological framework. Bakhtin is just as conscious as Frye is of the development of literary structures from myth. The comic novel in the hands of Rabelais, Cervantes, or Dostoevsky, manifests, in Bakhtin’s view, the myth of a collective social body conceived of in the metaphoric form of a giant human body which is born, grows, dies, and renews itself in the course of time. This powerful image of a self-renewing collective human form is strongest in Rabelais, but extends throughout Bakhtin’s work. It is, for example, clearly implied in the insistent anatomical imagery that pervades his writings on the novel, as in the opening paragraph of “Epic and Novel”: “The generic skeleton of the novel is still far from having hardened, and we cannot foresee all its plastic possibilities” (1981: 3); he speaks of the “hardened and no longer flexible skeleton” of genres and of “the establishment and growth of a generic skeleton of literature” (5). This recurrent image of a “generic skeleton” applied to the archaic form of the novel is linked metaphorically to the genre of anatomy as “a comical operation of dismemberment,” “the artistic logic of analysis, dismemberment, turning things into dead objects” (24). There is, then, a dramatic unifying tendency in Bakhtin’s conception of the novel which, in its assumption of an animating mythological framework, is analogous to Frye’s even more ambitious unification of the entire corpus of literature.

Frye sees the circle of mythoi, of which satire or sparagmos is one episode, as being contained in the arche-story of the dragon-killing theme, condensed so tidily in the following summary: “A land ruled by a helpless old king is laid waste by a sea-monster, to whom one young person after another is offered to be devoured, until the lot falls on the king’s daughter: at that point the hero arrives, kills the dragon, marries the daughter, and succeeds to the kingdom” (1957: 189). This central quest-myth, composed of four distinguishable episodes in the life of the hero or divine being, has a comic shape: agon, or adventures; pathos, or death; sparagmos, or disappearance; and anagnorosis, or recognition. These episodes correspond to the four narrative radicals or mythoi that Frye details in the third essay of Anatomy of Criticism: romance, tragedy, irony (and satire), and comedy. It is here that we can recognize the great debt Frye owes to the compendious pioneering work of Frazer on the “dying god,” or to the theme of the white goddess as outlined by Robert Graves. Also important to Frye is the work of the group of British classicists of the early decades of this century, Gilbert Murray, Francis Cornford, and Jane Harrison, who uncovered in Greek rituals based on the myth of the dying god the origins of Classical tragedy and comedy. The scheme of Frye’s sequence of mythoi is largely drawn from Murray; his theory of comedy owes much to Cornford’s study, The Origins of Attic Comedy.

A reflection of the profound continuity of Frye’s work is the way he reasserts the development of literature from myth in Words with Power, which appeared only months before his death; he refers at one point to Thorkild Jacobsen’s Treasures of Darkness, which is a more up-to-date examination of the dying gods of fertility in pre-Biblical Mesopotamian culture. This study, and others like it, such as Theodor Gaster’s Thespis, which examines the derivation of early forms of drama from ritual and myth in the cultures of the ancient Near East, provides a fascinating glimpse into the genesis and the logic of the conventions found in literature. In Words, Frye shows how the poetic imagery and narrative structures that derive from myth are an expression of the primary human concerns of “making a living, making love, and struggling to stay free and alive” (43); that is, of food and drink, sex, freedom of movement, and property. Ultimately, the latter concern with property or with human extensions of power concerns the instruments of mental production and the expansive energy and consciousness belonging to an imaginative vision of reality. In Frye’s view, it is this power alone, the power of the arts and sciences to “show us the human world that man is trying to build out of nature” (1988: 44), that has any hope of delivering humanity from the ghastly cycle of history and the ordinary limitations of physical and social reality.

In an analogous way, behind Bakhtin’s “comic” vision of the novel lies a faith in “unlimited human potential” (1981: 241), in the creative power of human beings to transform the natural and social order, a faith that is embodied in his revolutionary theory of the novel as the artistic form of modern history corresponding to an unprecedented expansion of human knowledge and creativity. He finds the novel’s revolutionary potential best exemplified in Rabelais’s work where “All historical limits are, as it were, destroyed and swept away by laughter. The field remains open to human nature, to a free unfolding of all the possibilities inherent in man” (1981: 240). Paradoxically, the authentic image of this modern liberation of human potential is derived from what Bakhtin calls the folkloric chronotope. Very close to Frye’s insight that poetic imagery is an outgrowth of primary concerns is Bakhtin’s insistence on the poetic significance of the matrix of objects and phenomena–food, drink, copulation, birth and death–that forms the rhythm of folkloric time-space.

Continue reading →