Dieric Bouts the Elder, Elijah in the Desert, ca. 1465

Lecture 18. February 17, 1948

In tragedy, something comes through directly, a vision beyond that of the social and the moral. Iago is a figure in a tragedy but he is not heroic. Macbeth is an experiment in a tragedy where the hero and the villain are the same person. Emotions of pity for the hero through the reproach of the audience somewhere; for example, they blame Iago. In a social tragedy, such as the lynching of a negro, the audience is morally condemned for tolerating such cruelty. A tragedy in which man is innocent and blames God for the scheme of things is not a real tragedy. Even Henley’s Invictus—“I am captain of my soul”—is still handing out a high moral line.

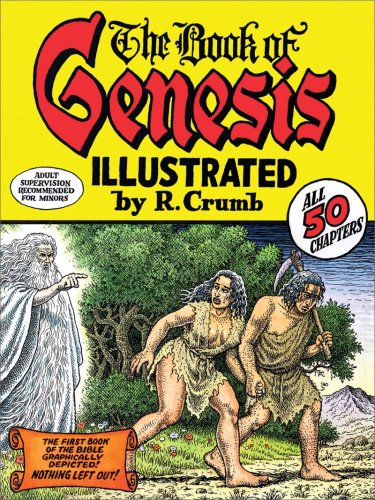

Job gets past this morality stage. He will not condemn himself, and therefore his three friends have nothing more to say. At this point, Job leaves the moral aspect and goes on to the tragic. Elihu has an organic role because he brings the tragedy to a focus.

The arguments with the friends are based on law. Wisdom means following the tried and tested ways––the fool is he who breaks away, etc. Yet, the law has not brought Job the wisdom he wants.

Elihu is the Old Testament conception of the prophet. He has no personal authority––I must speak; therefore it is God talking to you. The three friends are the old men of Job’s generation. Elihu is the young spirit of prophecy. He condemns Job on grounds that are implicit rather than implicit. He places the condemnation on a broader basis and comes closer to the doctrine of original sin: Job is condemned because he exists. Elihu deals with the “otherness” of God from man. This is the first step in religious feeling, the sense of the opposition of the divine and the human; the feeling that man cannot reach God through the human means of reason, etc.

God himself breaks in on Elihu’s speech and pushes him aside. It sounds as if God was merely continuing his speech, but he turns it upside down. The same thing is being said, but from a different quarter. Elihu has found the scent somehow or other. The voice which is outside Job is Elihu, but when the voice is inside Job, it is God. The Lord answers Job out of a whirlwind, the symbol of confusion. It is confusion in terms of what is going on around him. That is, out of Elihu’s words without knowledge and the confusion they create in Job, comes God’s voice.

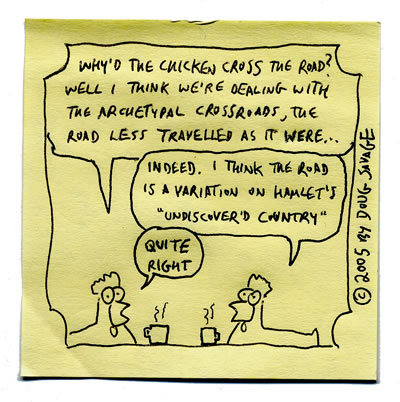

Elijah is the typical prophet, and Elihu’s name is close to his. Kings 1:19: Elijah repeats Jesus’ period in the wilderness and also Moses’ exile, so that he is the Law and the Prophet. Verse 9: the word of the Lord is represented by the pronoun “he.” And he said unto him, “What doest thou here, Elijah?” The action turns inside Elijah. He goes through the wind, earthquake, fire and doesn’t find God in any of them. But it is after the fire that there comes “a still small voice.”