httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NPzsklL0hLE

Palin blames “pundints” [sic] for “manufacturing a blood libel” against her

Roy Peter Clark cites Frye on metaphor to make some sense of Palin’s claim to be the victim of “blood libel” after the Tuscon shootings.

A sample:

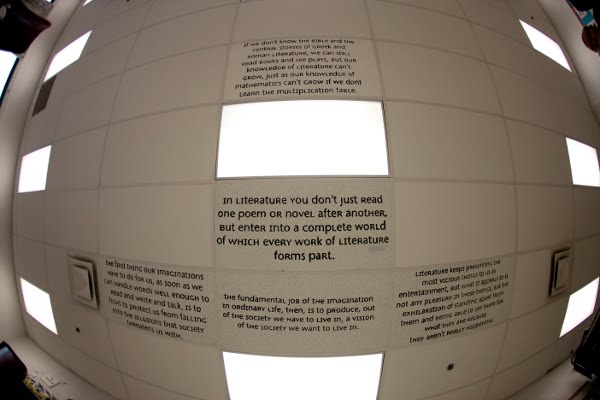

Frye provides a cautionary lesson about metaphorical language: that the differences between the compared elements are as important as the similarities. If I present myself as a “light to the world,” I am asking my audience to see my divine qualities and will not blame them for observing the dissimilarities.

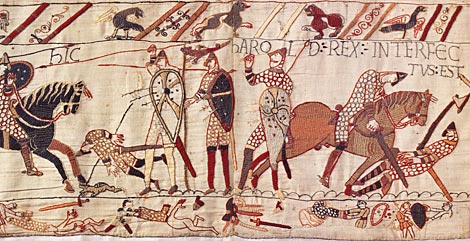

To describe oneself as a victim of blood libel carries with it a certain responsibility for proportionality, that the seriousness of the metaphor must equate in some measure with the experience being described. While the football game between the Steelers and the Ravens has already been compared to a war – and the players to gladiators – we recognize that as traditional and hyperbolic. But I would not call a failed athletic performance an “abortion” or a blowout of one team by another as a “holocaust” or “a virtual Hiroshima.”