1. In letter to Helen Kemp, 15 July 1932.

A man with a bad case of phthisis

Kept asking his family for phkhisses

Until his wife said,

“You can’t see your head

So you don’t know how rotten your phphiz is.”

2. In letter to Helen Frye, 5 January 1939.

I could fly as straight as an arrow,

To visit my wife over there,

If I could excrete my marrow,

And fill my bones with air.

3. Sonnet written on Frye’s 23rd birthday (14 July 1935). In a letter to Roy Daniells. Frye refers to it as “horrible doggerel, like all of my alleged poetry.”

Milton considered his declining spring

And realized the possibility

That while he mused on Horton scenery

Genius might join his youth in taking wing;

Yet thought this not too serious a thing

Because of God’s well-known propensity

To take and re-absorb inscrutably

The lives of men, whatever gifts they bring.

Of course I have a different heritage;

I’ve worked hard not to be young at all,

With fair results; at least my blood is cooled,

And I am safe in saying, at Milton’s age,

That if Time pays me an informal call

And tries to steal my youth, Time will get fooled.

4. Among the annotations Frye made in his copy of The Wisdom of Laotse (1948, trans. Lin Yutang) is this holograph verse at the end of chapter 4.

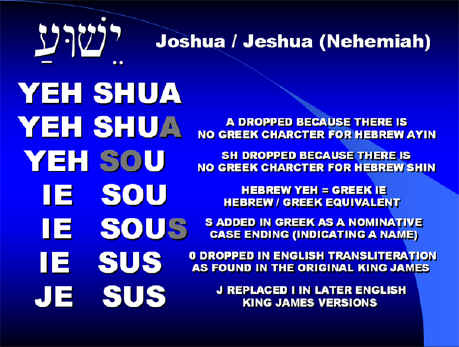

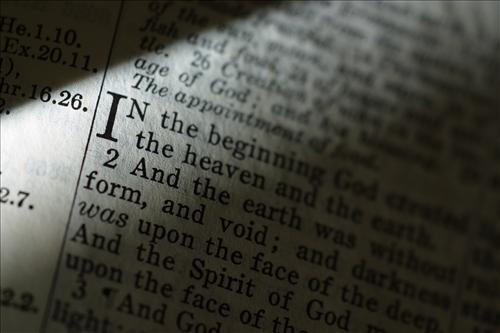

Laotse’s Commentary of Genesis

In the beginning God created heaven and earth.

That was where the trouble started.

Before, there was chaos,

Which is what the wise man still seeks.

He divided light from darkness, dry land from sea,

But we got sea and darkness anyway.

Silly blundering old bugger,

Why couldn’t he have left well enough alone.

5. Among the annotations to Frye’s copy of Lady Murasaki’s The Tale of Genji, this couplet scribbled in the margin of page 153.

When night lets fall her sable hood

How may one know which dame one scrood?