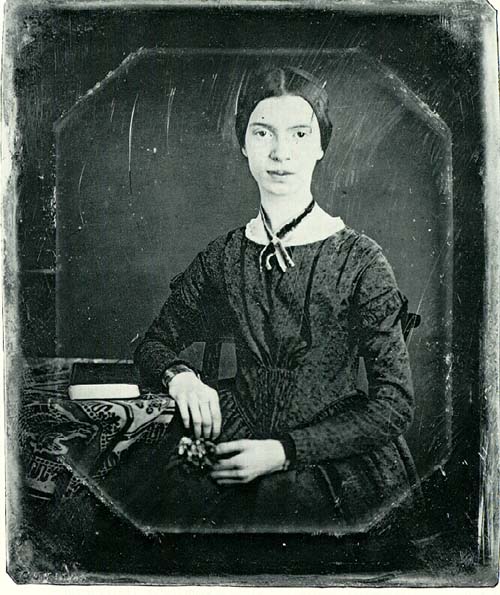

Dickinson at age 17. There is no authenticated later photo of her.

Today is Emily Dickinson‘s birthday (1830-1886).

Frye in “Emily Dickinson”:

Many, perhaps most, of Emily Dickinson’s readers will simply take their favorite poems from her and leave the rest, with little curiosity about the larger structure of her imagination. For many, too, the whole bent of her mind will seem irresponsible or morbid. It is perhaps as well that this should be so. “It is essential to the sanity of mankind,” the poet remarks, “that each one should think the other crazy.” There are more serious reasons: a certain perversity, and instinct for looking in the opposite direction from the rest of society, is frequent among creative minds. When the United States was beginning to develop an entrepreneur capitalism on a scale unprecedented in history, Thoreau retired to Walden to discover the meaning of the word “property,” and found that it meant only what was proper or essential to unfettered human life. When the Civil War was beginning to force on America the troubled vision of the revolutionary destiny, Emily Dickinson retired to her garden to remain, like Wordsworth’s skylark, within the kindred points of heaven and home. She will always have readers who will know what she means when she says, “Each of us gives or takes of heaven in corporeal person, for each of has the skill of life” [L388]. More restless minds will not relax from taking thought for the morrow to spend much time with her. But even some of them may still admire the energy and humour with which she fought her angel until she had forced out of him the crippling blessing of genius. (CW 17, 270)