Some observations in a time of transition (and at the start of a new academic year).

Frye’s claim that literary criticism was a science was quite controversial when the Anatomy of Criticism first appeared. One of the things that Frye meant by this claim was that criticism should be more inductive than deductive. Instead of applying a preconceived model from another discipline (his usual examples are Marxist, Freudian, and neo-Thomist criticism), the literary scholar should derive his or her conceptual framework “from an inductive survey of the literary field” (Anatomy of Criticism; Collected Works 22:9). The implications of this for the teaching of literature are obvious. From undergraduate curricula and required texts to PhD course requirements and comprehensive examination reading lists, the aim should be to survey as wide a range of the literary field as is possible.

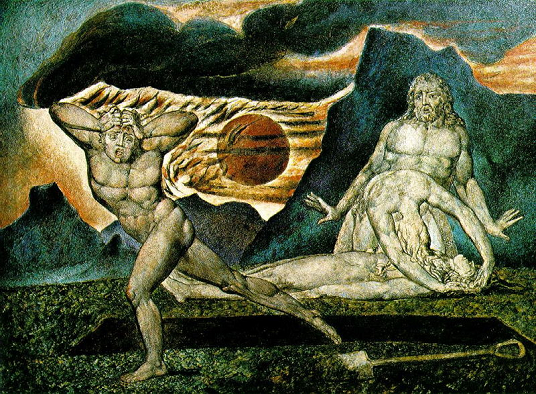

In terms of literary value, Frye of course famously opposed the idea that literary judgments could be demonstrated, but he was equally sure that some texts were more rewarding to study than others. The frequency with which he refers to Shakespeare and Milton would suggest that they should figure prominently in any programme of English-language literary education.

How do Frye’s ideas relate to the state of literary studies today? For one thing, as he observed through the decade before his death, some of the deterministic forms of criticism of his youth have returned, along with new but analogous models. At the same time, and as a result of some of these theoretical positions, the idea that there is a distinct literary field with certain established “monuments” has become much more problematic (there are a few exceptions such as Shakespeare, Jane Austen, and possibly Henry James).

In my own field of Victorian studies, I would like to make a modest defence of the idea that the aspiring scholar should make a fairly extensive inductive survey as part of his or her professional training. One useful barometer of the state of Victorian studies is the conversation on the VICTORIA listserv (which is archived here). It would be invidious to single out examples, especially since graduate students are often required to post questions on the list as part of a course requirement. But speaking generally, the questions that are posted sometimes reveal that students are able to reach the stage of independent research for their PhD in a state of apparent ignorance of what I would regard as key texts of relevance to their work. One well-known scholar lamented on the VICTORIA list a couple of years ago that courses require fewer and fewer texts, and those that are assigned tend to be shorter, so that Hard Times generally represents Dickens, to the exclusion of the longer and more characteristic works, while Thackeray is gradually disappearing from view altogether. Another Victorianist, elsewhere, notes sadly the fact the Oxford World’s Classics series no longer includes all of George Eliot’s novels. At the same time, the sensation novel has become far more prominent, so that Lady Audley’s Secret, once a vague rumour even to most PhD students, is now among the most frequently taught of all Victorian texts.

Obviously I have opened up larger questions about the changing nature of reading and education, which I will not develop here. Nor do I want to deplore in neoconservative manner all the recent developments in my field, some of which I have in fact contributed to. I am simply arguing that those of us who teach and who determine syllabuses and reading lists should consider our responsibility to promote the reading of a wide variety of Victorian texts, including novels such as Vanity Fair, David Copperfield, Bleak House, or the longer novels of George Eliot. Or, thinking of Frye’s own fascination with the Victorian sages, it would be nice if students were exposed to Carlyle, Ruskin, Mill, Arnold, and Newman more frequently than now tends to be the case. There is nothing wrong with studying Lady Audley’s Secret, whether as a Victorian scholar or in an undergraduate classroom, but Vanity Fair remains for me a more significant literary experience; just as, in Frye’s words, “The critic will find soon, and constantly, that Milton is a more rewarding and suggestive poet to work with than Blackmore” (CW 22:26). (Lest any of my fellow-Victorianists feel that I am chiding them for their choice of research topics or class texts, I admit to publishing on Dinah Maria Mulock and Charlotte Mary Yonge, and to teaching John Halifax Gentleman and Tom Brown’s Schooldays!) A last quotation from the Anatomy: “A critic may spend a thesis, a book, or even a life work on something that he candidly admits to be third-rate, simply because it is connected with something else he thinks sufficiently important for his pains” (CW 21:29).