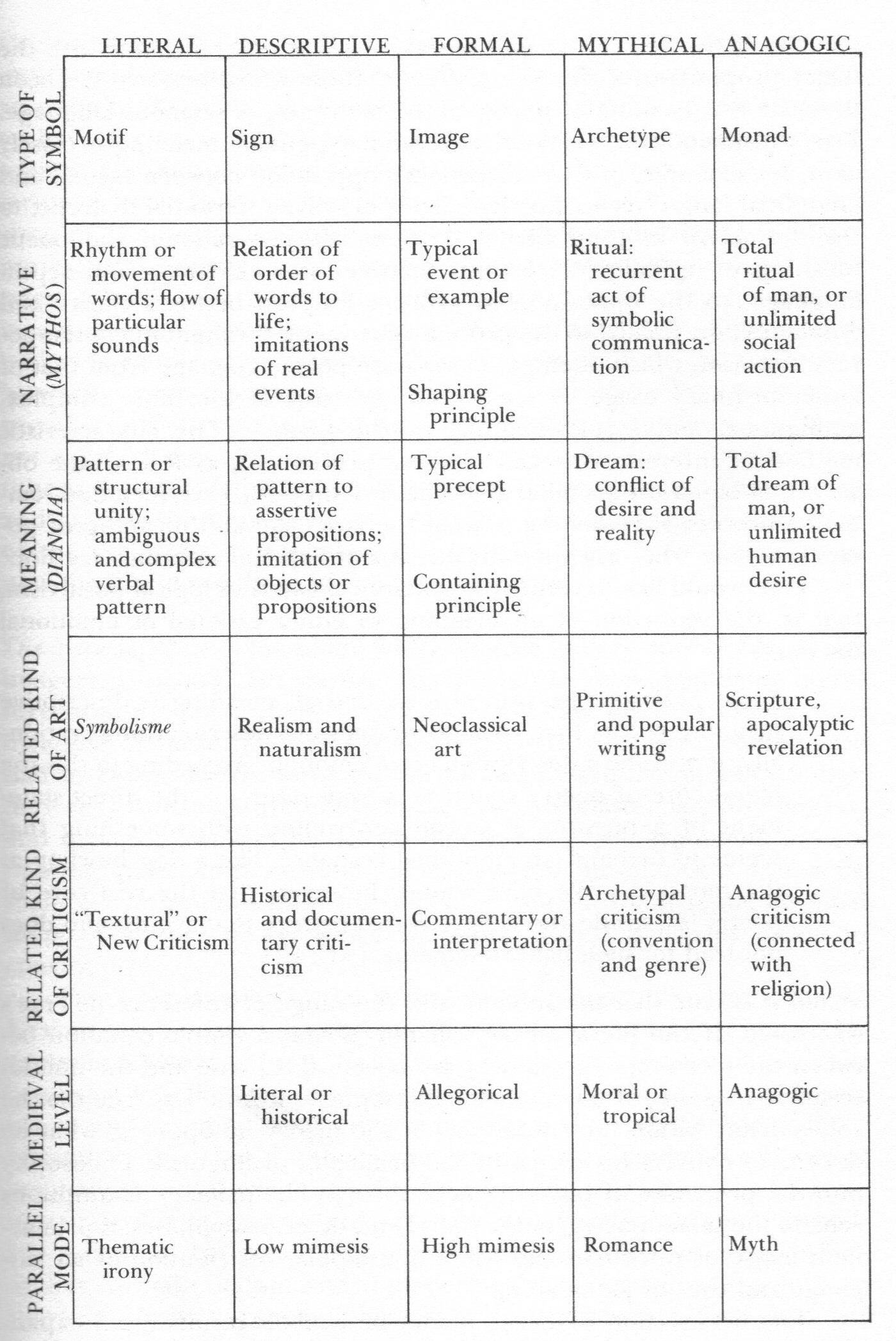

The Educated Imagination was the first book by Frye I read, and it’s therefore always a touchstone for me. You never forget your first love. Meanwhile, Fearful Symmetry remains Frye’s most mind-blowing text, The Great Code his most challenging, and Words With Power his most expansive for practical critical purposes. But like many Frygians, I’m guessing, I regularly return to Anatomy of Criticism, and, it seems, almost involuntarily. Every once in awhile I find myself preoccupied by something from it that I seem to recall out of the blue. Thanks to an email exchange with Peter Yan and the cumulative effect of posts over the last week or so, I have been pondering an issue Frye briefly raises in Anatomy that gets relatively little attention (the exception perhaps being Bob Denham’s Northrop Frye and Critical Method): “demonic modulation.”

With demonic modulation Frye makes a much needed distinction between “the moral” and “the desirable”:

The moral and the desirable have many important and significant connections, but still morality, which comes to terms with experience and necessity, is one thing, and desire, which tries to escape from necessity, is quite another. Thus literature is as a rule less inflexible than morality, and it owes much of its status as a liberal art to that fact. The qualities that religion and morality call ribald, obscene, subversive, lewd and blasphemous have an essential place in literature but often they can achieve expression only through ingenious techniques of displacement. (AC 156)

How does demonic modulation manage this? By way of “the deliberate reversal of the customary moral associations of archetypes.” For example, in literature, whatever the current status of received moral standards,

a free and equal society may be symbolized by a band of robbers, pirates, or gypsies; or true love may be symbolized by the triumph of an adulterous liaison over marriage, as in most triangle comedy; by a homosexual passion (if it is true love that is celebrated in Virgil’s second eclogue) or an incestuous one, as in many Romantics. (AC 156-7)

A.C. Hamilton in Northrop Frye: Anatomy of his Criticism describes Anatomy, published in 1957, as very much a book of its time — so Frye’s reference to various forms of forbidden love as “modulations” must have been eyebrow-raising for many conventionally-minded readers. Frye does not call it that here, but what he is clearly talking about is literature’s unique ability to express primary concerns beyond the pervasive gravitational pull of secondary ones.

I’m pretty sure I can remember the first time I ever became aware of this in my own reading experience: Graham Green’s The Power and the Glory, which was an assigned text back when I was in the 11th grade. I remember struggling with the contradiction between Greene’s “whiskey priest”‘s all too human frailty and his compelling nature as a human being I felt I could love and identify with, despite his obvious failings. I’m also pretty sure that even though I wondered about it at the time, I was nevertheless grateful to accept that it was so. Literature was showing me something I otherwise couldn’t account for with any certainty; and within a year I read The Educated Imagination for the first time which articulated what I in some sense already knew but simply could not yet say.

Literature references ideology but does not promote it. Literature gives expression to primary concerns, most especially when they are contrary to the ideologies that readily suppress them. Desire may on occasion be moral, but the moral can never contain desire — and in the struggle between the moral as a secondary concern and desire as a primary one, desire always prevails. That, paraphrasing Wilde’s Lady Bracknell, is what fiction means.