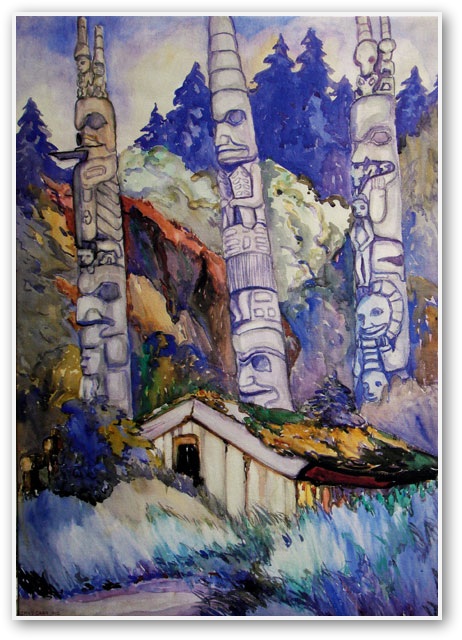

“Haida Totems”

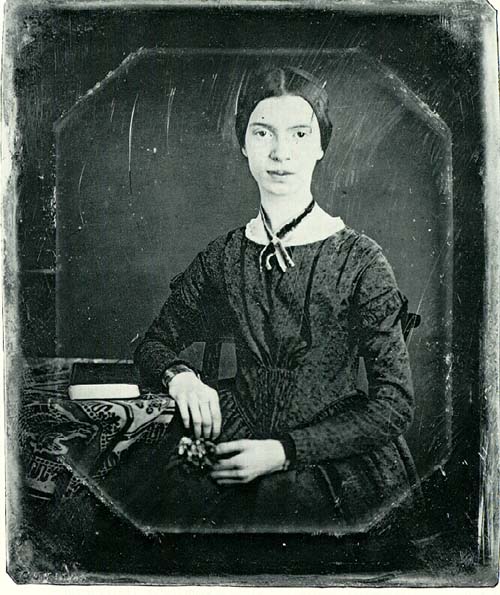

Today is Emily Carr‘s birthday (1871-1945).

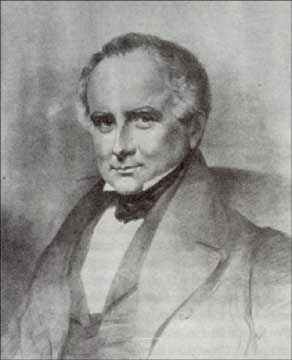

Frye was deeply interested in painting, and as a young reviewer seemed to have little patience for sniffy art criticism. See, for example, his 1939 Canadian Forum review, “Canadian Art in London,” which begins with an observation so dry that any hint of condescension would be immediately desiccated: “The Canadian Exhibition at the Tate Gallery was opened by a somewhat puzzled Duke of Kent, who said, according to the Times, that Canadian painting was very interesting, and that the really interesting thing about this exhibition was that it gave the English a chance to see this painting” (CW 12, 7).

Frye clearly enjoyed reviewing Canadian artists — not necessarily because he had any sort of patriotic bias, but because (knowing that all of the arts have deep roots in their native environment) he shared with them a Canadian experience that allowed him to see past the imperial prejudices of self-congratulatory more advanced tastes.

Here he is in the Christmas 1948 issue of Canadian Art, “The Pursuit of Form”:

Most painters choose a certain genre of painting, which in Canada is generally landscape, and commit themselves to the genius of that genre. Their growth as painters is thus a growth in sensitive receptivity. In comparing early and late work of a typical landscape painter, such as Arthur Lismer, once can see a steady increase in the power of articulating what he sees. The early work generalizes colour and abstract form; the late work brings out every possible detail of colour contrast and formal relationship with an almost primitive intensity. Emily Carr seems to go in the opposite direction, from the conventional to the conventionalized, from faithful detail to an equally intense abstraction. Yet there too the same growth in receptivity has taken place, the same power to express all the pictorial reality that she sees. (CW 12, 85)