Bob Denham’s post yesterday on Marshall McLuhan’s belief that Frye was part of a Masonic conspiracy against him, in part because of his esoteric reading list, raises the issue of Frye’s interest in what he called “kook books.” Here are a couple of examples from the notebooks.

For years I have been collecting and reading pop-science & semi-occult books, merely because I find them interesting. I now wonder if I couldn’t collect enough ideas from them for an essay on neo-natural theology. Some are very serious books I haven’t the mathematics (or the science) to follow: some are kook-books with their hair-raising insights or suggestions (CW 6, 713)

There’s a lot of semi-occult fascination with Atlantis in the last two centuries: one very fine book (despite its obvious weaknesses and lapses) is Merezhkovsky’s Atlantis/Europe, which tries to go all out for the historicity of Atlantis and doesn’t mention Thera, but is really based on an ascending ladder diagram in which we go up to the future, unless we get caught in the same cycle again, while Atlantis is our buried or forgotten past. He links the Timaeus and the Book of Enoch in some curious ways, coming close to a lot of the von Daniken mythology, but he’s better than that: an example of how yesterday’s kook book becomes tomorrow’s standard text. (CW 6, 495)

Bob Denham provides some context in his introduction to the Late Notebooks volumes:

Some of Frye’s reading is, if not altogether odd, at least surprising—books such as Merezhkovsky’s Atlantis/Europe and Maureen Duffy’s Erotic World of Faerie. Frye admits that Merezhkovsky comes “close to a lot of von Daniken mythology,” but then adds, “yesterday’s kook book becomes tomorrow’s standard text.” There are in the notebooks, as one might expect, a number of Frye’s old chestnuts—books such as Graves’s The White Goddess, Frances Yates’s studies in hermeticism, the mythical speculations of Gertrude Rachel Levy, Huxley’s Perennial Philosophy, Carroll’s Alice books, the novels of Bulwer-Lytton and Rider Haggard. But some readers will no doubt think it strange that Frye would even be curious about such books as Michael Baignet’s The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, Robert Anton Wilson’s The Cosmic Trigger, Marilyn Ferguson’s The Aquarian Conspiracy, Itzhak Bentov’s Stalking the Wild Pendulum, and A.E. Wait’s Quest of the Golden Stairs, The Pictorial Key to the Tarot, and The Holy Grail—“kook books” all. It would be difficult to imagine Frye citing such esoterica in Words with Power, but he does justify his interest in such writers as Waite, who is only “superficially off-putting”:

I’ve been reading Loomis and A.E. Waite on the Grail. Loomis often seem to me an erudite ass: he keeps applying standards of coherence and consistency to twelfth-century poets that might apply to Anthony Trolloppe. Waite seems equally erudite and not an ass. But I imagine Grail scholars would find Loomis useful and Waite expendable, because Waite isn’t looking for anything that would interest them. It’s quite possible that what Waite is looking for doesn’t exist—secret traditions, words of power, an esoteric authority higher than that of the Catholic Church—and yet the kind of thing he’s looking for is so infinitely more important than Loomis’ trivial games of descent from Irish sources where things get buggered up because the poets couldn’t distinguish cors meaning body from cors meaning horn. Things like this show me that I have a real function as a critic, pointing out that what Loomis does has been done and is dead, whereas what Waite does, even when mistaken, has hardly begun and is very much alive. (CW 5, xxxv-xxvi)

Michael Dolzani picks up the thread in the introduction to the “Third Book” Notebooks:

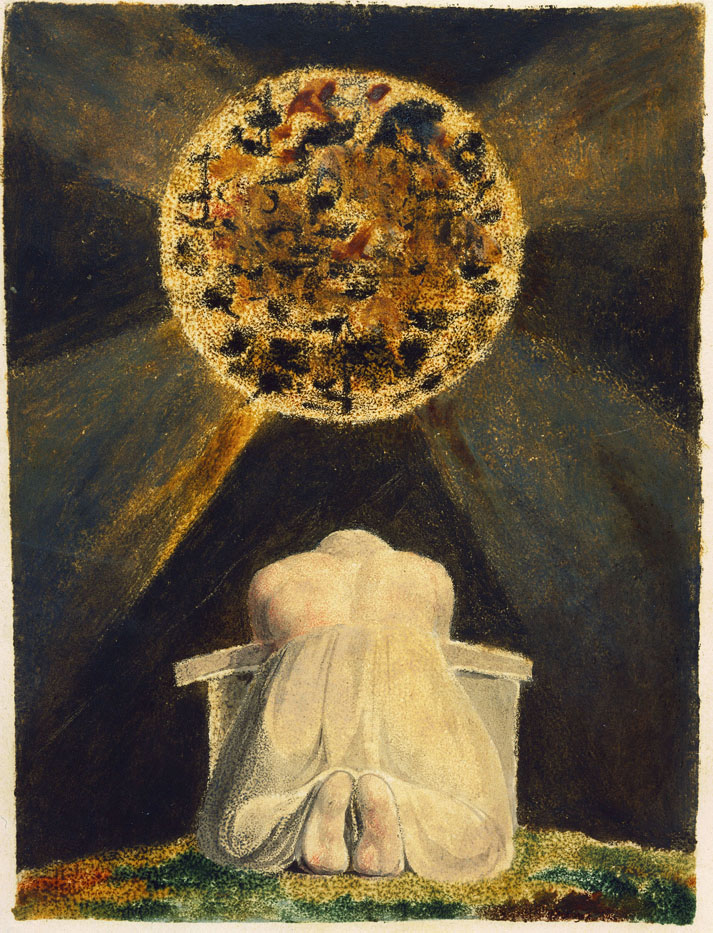

The notebooks are also more uninhibited than Frye’s published work, both intellectually and rhetorically. Frye’s speculations are much more open, more daring, sometimes breathtakingly so, and he is more willing to risk venturing upon works which professional prudence restrained him from making extended public comments upon, even if they had greatly influenced him. These include, on the one hand, works whose language or culture was not native to him; on the other, books of ill-repute with whom respectable scholars feel they cannot afford to be caught in public, what he called the “kook books” of unreserved mythopoeic speculation, from Jacob Boehme to Hamlet’s Mill, whose vision has affinities with his own project and which thus form part of its secret imaginative background even when their methods are flawed and their authors half-psychotic. (CW 9, xxii-xxiii)

See our Kook Books category, which includes more from Denham and Dolzani.